Conversations with Bhante Vimalaramsi #2

David Johnson interviews Bhante Vimalaramsi, a 30+ year American Buddhist Monk, on two important subjects. What is Mindfulness? A new definition based on the suttas is given by Bhante based on the Satipatthana Sutta. Based on this new definition of mindfulness this leads to a whole new type of Jhana, not an absorption jhana or state of concentration, but, rather, an aware relaxed, open state. So, there are two types of Jhana! What is confusing is that these two types of jhana are related and do have similar characteristics. The Buddha had rejected the concentration states that he found in the first few years of his journey; later he found a different type of jhana. Bhante discusses what this is. What is Craving? Bhante talks about tension and tightness.

Transcript

Hello,

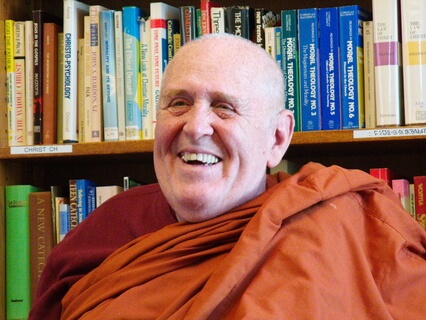

My name is David Johnson and I'm here with Bhante Vimalaramsi.

He studied history at the University of San Diego.

He became a Buddhist monk in Thailand in 1986 and has been in the robes ever since.

He's trained in Thailand,

Burma and Sri Lanka.

He's done many many retreats in the Mahasi Sayadah tradition but now has found his own path that has taken him back to the teachings found in the sutras themselves.

He teaches retreats at his Missouri center in the US and conducts retreats in Asia and around the world.

He is the author of many books including his major book on meditation,

Life is Meditation,

Meditation is Life.

We'll be doing a number of interviews so we won't cover everything in this one discussion.

This will be,

I believe,

The second one of a number of them to come.

We'll move into other areas and I also have a number of questions from social media that have been submitted.

A major subject in Buddhism because it's on everybody's minds and that is the topic of mindfulness and what is mindfulness.

What is mindfulness according to the Buddha's teaching?

Now they're using the word mindfulness in a lot of different,

With a lot of different definitions but with the Buddha's teaching and his meditation,

Mindfulness is remembering to observe how mind's attention moves from one thing to another.

When your mind is on your object of meditation and there's a distraction,

Mindfulness is the thing that shows you how your attention moves.

We don't care about why,

We want to know how attention moves from one thing to another.

When you look at it this way,

You start looking more deeply at how the links of dependent origination actually work.

So it's a real important thing to understand that there's an awful lot of talk about mindfulness but when we're talking about mindfulness with Buddhist meditation,

It has a different definition and I'm real big on giving definitions because there's so many misunderstandings that are occurring right now.

Now isn't the Pali word for mindfulness sati?

Sati yes it is.

And what does that really mean?

What is the difference between sati versus what is being taught in the very many mindfulness courses today?

Well the mindfulness courses today are teaching about psychological things which isn't bad but it doesn't help to use those kind of definitions when you're learning about meditation.

It's real important to understand that Buddhist terminology can be a lot different than a regular dictionary terminology.

And if you look it up in the dictionary,

Mindfulness says it's just awareness.

But if you use this definition of remembering to observe how mind's attention moves from one thing to another,

You're going to look at things more deeply.

So the way that mindfulness is being used right now by an awful lot of people is not wrong but it's not the same as the mindfulness that the Buddha taught.

Can you explain how it is being taught today?

Well it's just being taught surfacely about how to be aware of things when they arise.

Part of the problem with just using it as awareness is that there is no deep understanding of the importance of being able to see craving,

To recognize what craving is,

How to recognize what craving is,

How to let go of that craving.

When they're using just mindfulness as a word it doesn't incorporate all of the things that the Buddha was talking about.

For example if you're mindful of your breath,

Aren't you watching your breath at the belly going in and out and focusing,

Concentrating on it?

Or the nostril tip.

One of the things with the instructions in the suttas is it doesn't tell you to focus on your breath.

It says you understand when you take a long breath and when you take a short breath.

You know when you're breathing.

It doesn't mention nostril tip,

It doesn't mention upper lip,

It doesn't mention the movement of the abdomen.

It just says you understand when you take a long breath and when you take a short breath.

And you understand when your breath is being very coarse and very subtle.

You understand.

That means you know.

You know by simple observation.

So you're not drilling down into that sensation to really pick it apart and see what it looks like.

Right.

One of the things that's being taught today is that there's a difference between straight vipassana meditation and jhana practice,

Which doesn't agree with what it says in the suttas.

Almost everyone is practicing focusing on the breath and when you use the word focus you want to see the start of the in breath,

The middle of the in breath,

The ending of the in breath,

The pause in between and then you do the same with the out breath.

But that is not according to the suttas.

That is according to commentaries.

Sometimes I use commentaries but I use them when they agree with what it says in the suttas and that's a big difference.

Another thing in the instructions it says he trains thus.

Now you're getting to the actual meditation.

When he trains thus that means this is what you're training yourself to be mindful of.

How does this happen?

The important thing to understand in this next section is it's not talking about the over focus of the breath.

It's talking about the entire body.

Not the body of breath but the body,

The physical body.

This is the brain and there is a membrane that goes around each lobe that is called the meninges.

The meninges is basically a bag that holds the brain together.

Every time you have a thought,

Every time you have a feeling arise,

Every time there is a sensation,

Brain expands a little bit and causes tension and tightness to arise in your head.

When you're using mindfulness correctly you're seeing for yourself how this process works.

What happens first?

You recognize that your mind is not with the breath at that time.

How did that happen?

What happened first?

What happened after that?

What happened after that?

Next you follow the instructions which is part of right effort which is a very important part of the Eightfold Path.

In right effort you recognize that your mind is distracted.

The second part is that you release the distraction.

You don't keep your attention on the distraction.

And you relax the tightness caused by that distraction.

What is the tightness?

The tightness is that tightness in your head.

And the meninges goes all the way down your spine.

So this is experiencing the entire body.

Okay,

And there's tightnesses that can happen all over your body.

But it starts from the meninges being around the spinal cord and around the brain.

Now craving is an interesting thing in that it is the I like it,

I don't like it mind.

A pleasant feeling arises,

I like it.

I want it to stay.

It's a good feeling.

A painful feeling arises,

I don't like it,

I want it to stop.

This is the very beginning of craving.

Now when you're learning how to let go of the craving then you see how this process is working with your mindfulness,

How it works.

We don't care why.

We don't care about the substance of the thought or feeling.

What we do care about is the tightness that happens around your head,

Around your mind,

Or in your mind.

So I have a question for you.

Why can't we just ignore that tightness?

Many meditation teachers,

They teach the breath and they say if a thought comes up just ignore it and get your mind back to your object of meditation.

Because you're not recognizing that craving that is there and you're not letting it go.

This leads to a different kind of jhana.

Wait a minute,

You're saying that there's two types of jhana?

Absolutely.

The first kind of jhana I call one-pointed,

Sometimes they call it absorption.

That includes Kanaka Samadhi,

Upacara Samadhi,

And Apana Samadhi.

Why does it include these three different kinds of concentration?

It is because there is no letting go of the craving.

The thing that you hear a lot about now,

I've been doing meditation for over 40 years.

I have a lot of friends that have been doing meditation for that long or even longer.

And they don't recognize that craving.

Now what happens is that the force of the concentration,

That one-pointed kind of concentration,

The force of that concentration is so strong that it suppresses the hindrances while you're in the jhana.

It doesn't make the hindrance go away.

When you lose your concentration and you get back to your daily life,

You don't see any real personality development.

I hear a lot about people that have been practicing for many years,

They still have fear,

They still have anger,

They aren't purifying their mind because they're not letting go of the craving.

They're not recognizing the craving.

Now I've done probably somewhere around 12 three-month retreats with the Mahasi style meditation.

I did an eight-month retreat at Mahasi center,

I did a two-year retreat at Chamayeta in Burma who was teaching Mahasi style meditation.

When I was doing walking meditation,

I always had tension and tightness in my head.

And I would go to the teacher and I would say,

I have this tightness.

And he would say,

Ignore it,

It's nothing.

So he was encouraging me to do a type of one-pointed concentration.

What is that,

Where is that tightness coming from?

From craving.

Is it because you were trying too hard or?

Well it's all of those.

Just simply trying or?

Yeah,

And trying to,

On the surface,

Tell yourself this isn't me,

This isn't mine,

But you're not letting go of the cause of the suffering,

You're trying to push that suffering away.

And who's trying to control these distractions?

And who's trying to control them?

Which ones is you?

Is it the distraction is you or the controller?

That's what I'd really like to know.

Well the whole thing is,

If you don't let go of craving,

It is craving that is the controller.

It is the want for something to be a little bit different than it is.

And that gets into clinging and really identifying with this stuff.

But when you start using Right Effort,

The next part of Right Effort after you relax is that you see your mind is clear,

Your mind is bright,

Your awareness is very agile,

And your mind is pure.

Why is it pure?

Because you have let go of the craving.

Now the next part of Right Effort,

It says to bring up something wholesome.

What I teach is that I want you to have a light mind,

So I teach you to smile.

And I get criticized for teaching smiling,

But that is a wholesome state.

And it's okay to bring up that wholesome state.

And right after you smile,

You bring that pure mind that doesn't have any craving or clinging in it back to your object of meditation.

If it's the breath,

Then you come back to the breath,

On the in-breath,

It says to relax that tightness in your head and your mind.

This is the fourth part of the instruction.

It says literally to tranquilize the bodily formation.

And how do you tranquilize your bodily formation?

By letting go of the craving that tranquilizes all the way down your back.

And it tranquilizes your entire body.

The last part is to stay with your object of meditation for as long as you can.

Now almost everybody that's teaching meditation as far as I know in this country,

And I don't know everything that's being taught,

So I don't even pretend to know.

What's happening is your mind is on your object of meditation,

It gets distracted,

Then some methods say,

Well just watch it until it goes away.

And then immediately come back to what they call the primary object of meditation.

Now that sounds like noting.

That sounds like noting?

Noting,

Yes it is.

The practice of noting things as they come up?

And staying with them until they go away,

But that doesn't agree with the right effort.

And what if it doesn't go away?

What if there's a loud sound and it goes all day?

Then what do you do?

Well I had that experience when I was in Burma.

I was at Chamyayeta and they decided it was time to drill a well right outside the meditation center.

And they had this old engine that was running the drill and it was real loud.

I ignored it.

I ignored the sound after a while.

It wasn't a big deal.

It was only sound.

But people that are practicing one-pointed concentration,

What happens is if they hear any kind of a sound,

It makes them boink.

It makes them shocked.

And they don't like it.

So they get into their dislike of that situation.

And they've lost their meditation when they do that.

They're not following the instructions in the meditation.

A sound is just a sound.

That's what I had to come up with.

I mean it was there.

It was really there.

And it lasted until about six o'clock in the evening.

And then there was about a half an hour break.

Burma being Burma,

It was time for the tea shops to come out.

And they had loud speakers that were playing music.

Now,

I know there were some people that were complaining about all the sounds and that sort of thing.

They left.

Oh,

I have to be where it's quiet.

I did a retreat in New Mexico.

And it was 95 degrees in the meditation hall.

And they wanted to turn the fan off because it made too much noise.

Is that true mindfulness?

Are they seeing how this arises?

Or are they judging and condemning sound because it's there?

Is that the practice of the Buddha?

No.

It's only a sound.

So what you're saying is that instead of the sound,

They should be paying attention to the upset mind that is coming up,

The dislike,

And to relax into that.

And I've been teaching meditation for a long,

Long time.

And when I have students that come to me that have been doing other practices,

The first thing I have to get them to do is stop trying so hard.

Stop trying to force things to be as perfect as you want them to be.

That doesn't work and there's craving in it.

When your meditation is going the way the Buddha teaches,

What happens is that sound is there and you'll hear it.

But it doesn't make your mind wiggle.

It doesn't make your mind run to it and have this dislike.

It's only a sound.

What's the difference between a sound and a sight?

Well,

It's a different sense store.

That's the only difference.

So when you handle distractions like that,

This,

You're saying,

Leads to a different kind of jhana.

Yes,

Absolutely.

What kind of jhana is that?

It's a concentration jhana that is very,

Very similar to some of the commentaries where they divide jhana practice with vipassana.

They put that division in there to make it two separate kinds of practice.

That doesn't agree with the suttas at all.

There's a lot of ideas that have been springing up in the last 20 years or 30 years in the meditation itself that you can do the jhana practice and when you come out,

Then you do the vipassana and then you can become awakened.

But I haven't met anybody that has truly become awakened with that practice.

I've read that,

But I've never read anything,

You're right,

Where anybody has actually been successful with that.

Right.

But let's get back to that there's two types of jhana.

What is the jhana that you're proposing exists that seems to be,

Nobody seems to know about it.

Well,

An awful lot of people do know about it and they're very successful.

You're students,

Yes.

The thing is,

With one pointed concentration,

Because it's pushing the hindrances down,

The hindrances will always come up.

If you're noting it until it goes away,

It's going to still come up with your daily activities.

There is no real personality development with one pointed concentration.

And as I said,

I've done a lot of different kinds of meditation.

I do understand one pointed concentration very well.

I do understand vipassana very well.

But the end result of those practices does not agree with what the Buddha is teaching.

And this is why an awful lot of my friends that have been meditating for a long time,

They keep meditating in the same way.

And they keep getting the same end result,

Which doesn't lead to a happier mind,

A mind that's more accepting of things as they arise.

It's not letting go of that craving mind.

And this is why people talk about hitting a wall.

I went to one talk that somebody gave.

And this woman said,

I've been doing meditation for 10 years,

Straight vipassana.

When am I going to see less suffering?

And the answer for the student was,

Well,

You have to grin and bear it.

It'll happen in its own time.

What kind of an answer is that?

When you practice by putting this one extra step into your practice of relaxing that tension and tightness,

You're purifying your mind.

And there is personality change.

So what do you call these jhanas that you're teaching?

I mean,

I've heard light jhana,

Heavy jhana.

Well,

I don't,

They're still talking about one pointed concentration.

They're talking about this.

What I'm doing is teaching what the suttas say.

And we're calling it tranquil wisdom insight meditation,

TWIM.

Because there are insights.

They're not the same as the vipassana insights.

Now for instance,

You're going to go deeper,

Faster with this kind of meditation than with any other kind of meditation you've run across.

Now you have to understand,

During the time of the Buddha,

He had to come up with a kind of meditation that worked,

Worked quickly,

And there was change that was happening with personalities.

And it's a very important aspect that if you just add,

If you want to keep doing straight vipassana,

Add that relaxed step and you'll see the changes that start to happen.

This one step that's being ignored,

And it was ignored by Mahāsī Sayādā,

It was ignored by Venerable Uṣīla Nanda,

It was ignored by Venerable Sayādā Ujānika.

They just,

They didn't understand what it was talking about because they were spending so much time with their Abhidhamma and their commentaries that they didn't delve deep into the suttas.

Even today,

When you go to Sri Lanka where they have monk universities,

They have three semesters,

If that's what they call them,

I don't remember,

Of studying the Vāsudī Magga and one class of studying suttas,

And that includes almost exclusively the Satipatthana Sutta.

So they really don't get a grasp of what the Buddha is teaching because they're spending so much time with other things.

But let me ask,

Let's go back to jhanas.

In the Anupāda Sutta,

It very clearly identifies eight different levels of jhana.

Now are those not concentration jhanas or what kind of jhana are they?

What does the word jhana mean anyway?

Well almost everybody says jhana means concentration.

That's what it means.

By my studies I found out that jhana means a level of your understanding.

Understanding what?

How to remember how mind's attention moves from one thing to another.

And that happens while you're in the jhana.

You're not exclusively on one point only.

And because of that,

Your awareness is much sharper of things when they first start to arise and you can see that,

Relax,

Let it be,

Purify your mind and continue on.

Now does your breath stop when this happens,

The fourth jhana,

And you don't hear anything and all that sort of thing in these jhanas?

You have all of the sense doors.

But when you get to the fourth jhana you don't have sensation in your body but you still have the sense doors.

And the only time the sense door arises is when there is some kind of contact.

What is contact?

Well for instance you're sitting and an ant starts walking across your arm.

You would feel that.

But it doesn't make your mind shake and go to it.

You recognize that it's there and you let it be and not do anything with it.

And it's the same with sound.

When there's a sound and inevitably it doesn't matter where you practice,

You're going to have sounds.

But it doesn't make your mind shake and go to it.

Sound just kind of goes through you.

Okay,

I know it was there.

So that going to it,

Isn't that,

It must be craving itself,

Wanting to hear that sound?

Well it's not,

It's a little bit more subtle than that.

It's not I want to hear a sound.

It arises because a feeling arose first.

First there was contact,

Then there was feeling,

Then there was craving.

And it's not like you are doing any of these things.

This is how the process works.

And this process is called dependent origination.

That's why I said in the last interview that dependent origination is the backbone of the Buddha's teaching.

And this is how all of this stuff arises.

And it arises on its own.

It's impersonal.

You don't ask a sound to come up.

A sound comes up when the conditions are right for it to come up.

What you do with what arises in the present dictates what happens in the future.

If you don't like that sound,

You start thinking about the stories about how you don't like it and you are involved in the emotional upset.

Now you are completely away from your object of meditation.

You haven't practiced your mindfulness because you are taking it all personally.

Another one.

I have a friend that's been practicing for a long,

Long time.

And when he first started practicing,

He had a problem with fear arising.

He started to be a teacher and he was afraid when he was giving Dhamma talks.

He was very shy of that.

He still has that fear to this day.

Now does that mean that he's purifying his mind?

Is he letting go of that fear and not identifying with it?

Or is he trying a psychological approach of,

Well,

It's there and it's okay for it to be there.

And it bothers me a little bit but I'm not going to get involved with it.

The Buddha's practice is about purifying your mind.

Now do you need jhanas to purify your mind?

I mean why?

Mahasisthayada says you don't need to practice any sort of jhanas.

They take way too long.

The Mahasisthayada practiced jhana.

Really?

He did.

He did practice jhana.

And he was actually pretty good at it.

And he did get some psychic abilities along with it.

I've always heard that you're not supposed to be attached to jhanas.

They're too blissful.

Well it is blissful and you can get attached to it but you don't have to.

What you do with what arises in the present dictates what happens in the future.

When you take it personally and you like it and you want it to stay around and you get real involved with it,

You're not being mindful.

You're not seeing how the process works.

You're attached to the process and therein lies a lot of suffering.

We're supposed to be getting rid of suffering,

Not just grinning and bear it.

We're supposed to let it go.

And the way you do that is by relaxing the tension and tightness in your head and in your mind.

Because right after that your mind becomes very pure,

Your mind becomes very alert and there's no distraction in your mind.

Now some people are trying to teach,

Well there's no such a thing as a distraction,

All you have to do is watch all of this stuff.

Well there is a distraction because you're still taking it personally.

You're still identifying with it.

You're not letting it be and letting go of that attachment to it.

You're just kind of suppressing it for a while until it comes up again.

And that's with anger,

That's with anxiety,

That's with sadness,

That's with whatever arises.

If you just watch it enough and you say,

Well there's nothing to it and it's not mine really,

You're suppressing seeing the Dhamma.

The truth is when these things arise,

They're there.

What are you going to do with it?

If you're going to fight with it,

If you're going to try to control it,

If you're going to try to make it be something different than it is,

You're fighting with the Dhamma,

The truth of the present moment.

And I shouldn't say present moment because it doesn't say that in the suttas but it's an old habit I got into.

The truth of the present,

When you allow the present moment to be without getting involved with it,

You allow it to be,

You smile,

Lighten your mind,

Come back to your object of meditation,

You're going to stay with your object of meditation for a longer period of time.

And you're going to see for yourself a lot of insights into how mind works.

Well,

I think that's a good place to stop.

Thank you,

Bhante Vimalaramsi,

For your time.

And I hope people have gotten a little bit out of this discussion and we'll have a few more in the coming weeks.

4.8 (62)

Recent Reviews

Cary

May 21, 2023

I have heard a few taks and read some Books from his students but this talk was eye opening and wonderful. I would love to hear more 🙏🙏🙏

Christa

September 13, 2022

Excellent

Lluís

August 27, 2022

Very clarifying. Many thanks!

Steven

February 23, 2021

Perfect. Thank you. It was such a clear definition of Jhana. Steven

Tasha

July 18, 2019

Outstanding explanation in layman's terms, simplified with description I, as a beginner, could really use to help define my burgeoning practice. Thank you. Namaste 🙏

Eva

August 3, 2018

Very useful and clear. Thank you!

Theresa

August 3, 2018

Very insightful. I will listen again. 🙏🏻🌺

Yvonne

August 2, 2018

❤️very grateful for this great interview and talkings, big thanks, namaste. ❤️

Connie

August 2, 2018

Critical discussion! Thank you for pointing to mindfulness without addressing craving. If craving is ignored what is the benefit of simply pushing it away? Great teaching here!🌺🙏🏽🌺