The Railway Children Chapter 8: Bedtime Story

by Sally Clough

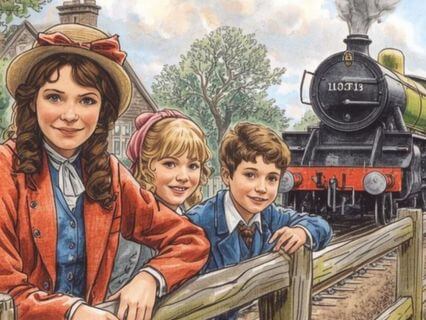

Hello beautiful souls, This is my reading of The Railway Children by Edith Nesbit, a beautiful story about three children who move from London to the countryside and fall in love with the railway. They face lots of trials and tribulations but have many exciting adventures along the way. This is a heart-warming story of love and resilience. This was one of my most cherished stories as a child. You can find all the chapters on my profile in the playlist section. I hope you enjoy this reading of a wonderful classic. Take care, beloveds.

Transcript

Hello dear ones and welcome to today's reading of The Railway Children by E.

Nesbitt.

Just before we begin,

Taking a moment to arrive here in the space,

In your body and reconnecting with your breath.

Feel the heaviness in your legs,

Feel your clothes touching your skin and notice where you feel the breath in your body,

Allowing your inhales and exhales to become longer.

And when you're ready,

We'll begin.

Chapter Eight The Amateur Fireman That's a likely little brooch you've got on miss,

Said Perks the porter.

I don't know as ever I see a thing more like a buttercup without it was a buttercup.

Yes,

Said Bobby,

Glad and flushed by this approval.

I always thought it was more like a buttercup almost than even a real one.

And I never thought it would come to be mine,

My very own.

And then mother gave it to me for my birthday.

Oh,

Have you had a birthday?

Birthday,

Said Perks,

And he seemed quite surprised as though a birthday were a thing only granted to a favoured few.

Yes,

Said Bobby.

When's your birthday,

Mr.

Perks?

The children were taking tea with Mr.

Perks in the porter's room.

They had brought their own cups and some jam turnovers.

Mr.

Perks made tea in a beer can,

As usual,

And everyone felt happy and confidential.

My birthday,

Said Perks,

Tipping some more dark brown tea out of the can into Peter's cup.

I give up keeping my birthday before you were born.

But you must have been born sometime,

Said Phyllis thoughtfully.

Even if it was 20 years ago,

Or 30,

Or 60,

Or 70.

Not so long as that,

Missus,

Perks grinned as he answered.

If you really want to know it was 32 years ago,

Come the 15th of this month.

Then why don't you keep it,

Asked Phyllis.

I've got something else to keep besides birthdays,

Said Perks.

Oh,

What?

Asked Phyllis eagerly.

Not secrets?

No,

Said Perks.

The kids and the missus.

It was this talk that set the children thinking and,

Presently,

Talking.

Perks was,

On the whole,

The dearest friend they had made.

Not so grand as the station master,

But more approachable.

Less powerful than the old gentleman,

But more confidential.

It seems horrid that nobody keeps his birthday,

Said Bobby.

Couldn't we do something?

Let's go up to Canal Bridge and talk it over,

Said Peter.

I got a new line this morning from the postman.

So,

They all went up to the Canal Bridge.

The idea was to fish from the bridge,

But the line was not quite long enough.

Never mind,

Said Bobby.

Let's just stay here and look at things.

Everything is so beautiful.

And it was.

The sun was setting in red splendour over the grey and purple hills.

And the canal lay smooth and shiny in the shadow.

No ripple broke its surface.

It was like a grey satin ribbon between the dusky green silk of the meadows that were on each side of its banks.

It's alright,

Said Peter.

But somehow,

I can always see how pretty things are much better when I've got something to do.

Let's get down on the towpath and fish from there.

Phyllis and Bobby remembered how the boys on the canal boats had thrown coals at them.

And they said so.

Oh,

Nonsense,

Said Peter.

There aren't any boys here now.

If there were,

I'd fight them.

Peter's sisters were kind enough not to remind him how he had not fought the boys when coal had last been thrown.

Instead,

They said,

Alright then,

And cautiously climbed down the steep bank to the towing path.

The line was carefully baited,

And for half an hour,

They fished patiently and in vain.

Not a single nibble came to nourish hope in their hearts.

All eyes were intent on the sluggish waters that earnestly pretended that they had never harboured a single fish,

When a loud,

Rough shout made them start.

Hey,

Said the shout,

In most disagreeable tones,

Get out of that,

Can't you?

An old white horse coming along the towing path was within a half a dozen yards of them.

They sprang to their feet and hastily climbed up the bank.

We'll slip down again when they've gone,

Said Bobby.

But alas,

The barge stopped under the bridge.

She's going to anchor,

Said Peter,

Just our luck.

The barge did not anchor,

Because an anchor is not part of a canal boat's furniture.

But she was moored with ropes,

And the ropes were made fast to the palings and to crowbars driven.

What are you staring at?

Growled the barge,

Crossly.

We weren't staring,

Said Bobby.

We wouldn't be so rude.

Get along with you,

Said the man.

Get along yourself,

Said Peter.

He remembered what he had said.

Get along yourself,

Said Peter.

He remembered what he had said about fighting boys.

And besides,

He felt safe halfway up the bank.

We've as much right to be here as anyone else.

Oh,

Have you indeed,

Said the man.

We'll soon see about that.

And he came across his deck and began to climb down the side of his barge.

Oh,

Come away,

Peter.

Do come away,

Said Bobby and Phyllis in agonized unison.

Not me,

Said Peter,

But you'd better.

The girls climbed to the top of the bank and stood ready to bolt for home as soon as they saw that their brother was out of danger.

The way home lay all downhill.

They knew that they all ran well.

The barge did not look as if he did.

He was red faced,

Heavy and beefy.

But as soon as his foot was on the towing path,

The children saw that they had misjudged him.

He made one spring up the bank and caught Peter by the leg,

Dragged him down and set him on his feet with a shake,

Saying sternly,

Now then,

What do you mean by it?

Don't you know these air waters is preserved?

You ain't no right catching fish here.

Not to say nothing of your precious cheek.

Peter was always proud afterwards when he saw his brother when he remembered that with the barge's furious fingers tightening on his ear,

The barge's crimson countenance close to his own,

The barge's hot breath on his neck,

He had the courage to speak the truth.

I wasn't catching fish,

Said Peter.

That's not your fault.

I'll be bound,

Said the man,

Giving Peter's ear a twist,

Not a hard one,

But still a twist.

Peter could not say that it was.

Bobby and Phyllis had been holding onto the railings above and skipping with anxiety.

Now,

Suddenly,

Bobby slipped through the railings and rushed down the bank toward Peter.

So impetuously that Phyllis,

Following more temperately,

Felt certain that her sister's descent would end in the waters of the canal.

And so it would have done if the barge hadn't let go of Peter's ear and caught her in his jerseyed arm.

Who were you shoving off?

He said,

Setting her on her feet.

Oh,

Said Bobby,

Breathless,

I'm not shoving anybody,

At least not on purpose.

Please don't be cross with Peter.

Of course,

It's your canal.

We're sorry,

And we won't fish anymore.

But we didn't know it was yours.

Go get along with you,

Said the barge.

Yes,

We will.

Indeed,

We will,

Said Bobby,

Earnestly.

But we do beg your pardon,

And really,

We haven't caught a single fish.

I'd tell you directly if we had.

She held out her hands,

And Phyllis turned out her little empty pocket,

To show that really,

They hadn't any fish concealed about them.

Well,

Said the barge,

More gently,

Cut along then,

And don't you do it again,

That's all.

The children hurried up the bank.

Took us a coat,

Maria,

Shouted the man.

And a red-haired woman,

In a green plaid shawl,

Came out from the cabin door,

With a baby in her arms,

And threw a coat to him.

He put it on,

Climbed to the bank,

And slouched along across the bridge,

Towards the village.

You'll find me up at the Rose and Crown,

When you've got the kid to sleep,

He called to her,

From the bridge.

When he was out of sight,

The children slowly returned.

Peter insisted on this.

The canal may belong to him,

He said,

Though I don't believe it does.

But the bridge is everybody's.

Dr.

Forrest told me it's public property.

I'm not going to be bounced off the bridge.

By him,

Or by anyone else,

So I tell you.

Peter's ear was still sore,

And so were his feelings.

I do wish you wouldn't.

Go home if you're afraid,

Said Peter.

Leave me alone,

I'm not afraid.

The sound of the man's footsteps died away,

Along the quiet road.

The peace of the evening was not broken by the notes of the sedge warblers,

Or by the voice of the woman in the barge,

Singing her baby to sleep.

It was a sad song she sang,

Something about Bill Bailey,

And how she wanted him to come home.

The children stood leaning their arms on the parapet of the bridge.

They were glad to be quiet for a few minutes,

Because all three hearts were beating much more quickly.

I'm not going to be driven away by any old bargeman.

I'm not,

Said Peter.

Of course not,

Phyllis said soothingly.

You didn't give in to him,

Peter.

So now,

We might go home,

Don't you think?

We might go home,

Don't you think?

Nothing more was said till the woman got off the barge,

Climbed the bank,

And came across the bridge.

She hesitated,

Looking at the three backs of the children.

Then she said,

Ahem.

Peter stayed as he was,

But the girls looked around.

You mustn't take no notice of my Bill,

Said the woman.

His bark's worse than his bite.

Some of the kids down Farley way,

They're fair terrors.

It was them who put his back up,

Calling out about who ate the puppy pie under Marlow Bridge.

But who did eat the pie?

Asked Phyllis.

I don't know,

Said the woman.

Nobody don't know.

But somehow,

And I don't know the why nor the wherefore of it,

Them words is prison to a barge master.

Don't you take no notice.

You won't be back for two hours,

Good.

You might catch a power of fish before that.

The light's good and all,

She added.

Thank you,

Said Bobby.

You are very kind.

Where's your baby?

Asleep in the cabin,

Said the woman.

He's all right.

Never wakes before 12.

Regular as a church clock he is.

Oh,

I'm sorry.

I would have liked to see him,

Said Bobby.

And a finer you never did see,

Miss,

Though I says it.

The woman's face brightened as she spoke.

Aren't you afraid to leave it?

Said Peter.

Lord love,

You know,

Said the woman.

Who'd hurt a little thing like him?

Besides,

Spots there.

So long,

Then.

The woman went away.

Shall we go home?

Said Phyllis.

You can.

I'm going to fish,

Said Peter.

I thought we came up here to talk about Perks's birthday,

Said Phyllis.

Perks's birthday'll keep.

So they got down on the towing path again and Peter fished.

He did not catch anything.

It was almost quite dark.

The girls were getting tired.

And as Bobby said,

It was past bedtime when suddenly Phyllis cried.

What's that?

And she pointed to the canal boat.

Smoke was coming from the chimney of the cabin.

Had indeed been curling softly into the soft evening air all the time.

But now other wreaths of smoke were rising.

And these were from the cabin door.

It's on fire.

That's all,

Said Peter calmly,

Serving right.

Oh,

How can you,

Peter?

Cried Phyllis.

Think of the poor dear dog.

The baby,

Screamed Bobby.

In an instant,

All three made for the barge.

Her mooring ropes were slack and the little breeze,

Hardly strong enough to be felt,

Had yet been strong enough to drift her stern against the bank.

Bobby was first.

Then came Peter.

And it was Peter who slipped and fell.

He went into the canal,

Up to his neck,

And his feet could not feel the bottom.

But his arm was on the edge of the barge.

Phyllis caught at his hair.

It hurt,

But it helped him to get out.

Next minute,

He had leaped onto the barge,

Phyllis following.

Not you,

He shouted to Bobby.

Me,

Let me because I'm wet.

He caught up with Bobby at the cabin door and flung her aside,

Very roughly indeed.

If they had been playing,

Such roughness would have made Bobby weep with tears of rage and pain.

Now,

Though he flung her onto the edge of the hold,

So that her knee and her elbow were grazed.

She only cried.

No,

Not you,

Peter,

Me.

And struggled up again,

But not quickly enough.

Peter had already gone down two of the cabin steps into the cloud of thick smoke.

He stopped,

Remembered all he had ever heard of fires,

Pulled his soaked handkerchief out of his breast pocket and tied it over his mouth.

As he pulled it out,

He said,

It's all right,

Hardly any fire at all.

And this,

Though he thought it was a lie,

Was rather good of Peter.

It was meant to keep Bobby from rushing after him into danger.

But of course,

It didn't.

The cabin glowed red.

A paraffin lamp was burning calmly in an orange mist.

Hi,

Said Peter,

Lifting the handkerchief from his mouth for a moment.

Hi,

Baby.

Where are you?

Oh,

Let me go,

Peter,

Cried Bobby close behind him.

Peter pushed her back more roughly than before and went on.

Now,

What would have happened if the baby hadn't cried?

I don't know.

But just at that moment,

It did cry.

Peter felt his way through the dark smoke,

Found something small and soft and warm and alive.

Picked it up and backed out,

Nearly tumbling over Bobby,

Who was close behind him.

A dog snapped at his leg,

Tried to bark,

But choked.

I've got the kid,

Said Peter,

Tearing off the handkerchief and staggering onto the deck.

Bobby caught at the place where the bark came from and her hands met on the fat mouth of a smooth-haired dog.

It turned and fastened its teeth on her hand,

But very gently,

As much as to say,

I'm bound to bark and bite if strangers come into my master's cabin.

But I know you mean well,

So I won't really bite.

Bobby dropped the dog.

All right,

Old man,

Good dog,

Said she.

Here,

Give me the baby,

Peter.

You're so wet,

You'll give it a cold.

Peter was only too glad to hand over the strange little bundle that squirmed and whimpered in his arms.

Now,

Bobby said quickly,

You run straight to the Rosencrown and tell them.

Phil and I will stay here with the precious.

Hush then,

Dear.

Oh,

Darling,

Such a ducky.

Go now,

Peter,

Run.

I can't run in these things,

Said Peter firmly.

They're as heavy as lead.

I'll walk.

Then I'll run,

Said Bobby.

Get on the bank,

Phil,

And I'll hand you the deer.

The baby was carefully handed over.

Phyllis sat down on the bank and tried to hush the baby.

Peter wrung the water from his sleeves and knickerbocker legs as well as he could.

And it was Bobby who ran like the wind across the bridge and up the long,

White,

Quiet twilight road towards the Rosencrown.

There is a nice old-fashioned room at the Rosencrown where Borgies and their wives sit of an evening,

Drinking their supper beer and toasting their supper cheese at a glowing basket full of coals that sticks out into the room under a great hooded chimney and is warmer and prettier and more comforting than any other fireplace I ever saw.

There was a pleasant party of Barge people around the fire.

You might not have thought it pleasant,

But they did,

For they were all friends or acquaintances and they liked the same sort of things and talked the same sort of talk.

This is the real secret of pleasant society.

The Bargy Bill,

Whom the children had found so disagreeable,

Was considered excellent company by his mates.

He was telling a tale of his own wrongs,

Always a thrilling subject.

Bill!

I want Bill the Bargeman!

There was a stupefied silence.

Pots of beer were held in mid-air,

Paralysed on their way to thirsty mouths.

Oh,

Said Bobby,

Seeing the Bargewoman and making for her.

Your barge cabin's on fire.

Go,

Quickly!

The woman started to her feet and put a big red hand to her waist on the left side.

Where your heart seems to be when you are frightened or miserable.

Reginald,

She cried in a terrible voice.

My Reginald!

All right,

Said Bobby.

If you mean the baby,

We got him out safe.

Dog,

Too.

She had no breath for more,

Except,

Go on,

Go.

It's all right.

Then she sank on the alehouse bench and tried to get that breath of relief after running,

Which people call the second wind.

But she felt as though she would never breathe again.

Bill the Bargee rose slowly and heavily,

But his wife was a hundred yards up the road before he had quite understood what was the matter.

Phyllis,

Shivering by the canal side,

Had hardly heard the quick approaching feet before the woman had flung herself on the railing,

Rolled down the bank and snatched the baby from her.

I'd just got him to sleep,

Said Phyllis,

Reproachfully.

Bill came up later,

Talking in a language talking in a language with which the children were wholly unfamiliar.

He leaped onto the barge and dipped up pails of water.

Peter helped him and they put out the fire.

Phyllis,

The barge woman and the baby,

And presently Bobby,

Too,

Cuddled together in a heap on the bank.

Lord,

Help me if it was me that left anything as could catch a light.

Said the woman again and again.

But it wasn't she.

It was Bill,

The bargeman,

Who had knocked his pipe out and the red ash had fallen on the hearth rug and smouldered here and at last broken into a flame.

Though a stern man,

He was just.

He did not blame his wife for what was his own fault,

As many bargemen and indeed many other men would have done.

Mother was half wild with anxiety when at last the three children turned up at the chimneys,

All very wet by now,

For Peter seemed to have come off on the others.

But when she had disentangled the truth of what had happened from their mixed and incoherent narrative,

She owned that they had done quite right and could not possibly have done otherwise.

Nor did she put any obstacles in the way of their accepting the cordial invitation which the bargeman had parted.

Ye be here at seven tomorrow and I'll take you the entire trip to Farley and back,

So I will,

And not a penny to pay.

Nineteen locks.

They did not know what locks were,

But they were at the bridge at seven,

With bread and cheese and half a soda cake and a quarter of a leg of mutton in a basket.

It was a glorious day.

The old white horse strained at the ropes,

The barge glided smoothly and steadily through the still water.

The sky was blue overhead.

Mr.

Bill was as nice as anyone could possibly be.

No one would have thought that he could be the same man who had held Peter by the ear yesterday.

As for Mrs.

Bill,

She had always been nice,

As Bobby said,

And so had the baby,

An even spot who might have bitten them quite badly if he had light.

It was simply ripping,

Mother,

Said Peter,

When they reached home very happy,

Very tired and very dirty.

Right over that glorious aqueduct and locks.

You don't know what they're like.

You sink into the ground and then,

When you feel like you're never going to stop going down,

Two great black gates open slowly and out you go.

And there you are on the canal,

Just like you were before.

I know,

Said mother.

There are locks on the Thames.

Father and I used to go on the river at Marlow before we were married.

And the dear,

Darling,

Ducky baby,

Said Bobby.

It let me nurse it for ages and ages.

It was so good,

Mother.

I wish we had a baby to play with.

And everybody was so nice to us,

Mother,

Said Phyllis.

Everybody we met.

And they say we may fish whenever we like.

And Billy's going to show us the next time he's here.

He says that we don't know how to really.

He said you didn't know,

Phyll,

Said Peter.

But mother,

He said he'd tell all the barges up and down the canal that we were the real right sort and that they were to treat us like good pals.

So then I said,

Phyllis interrupted,

We'd always each wear a red ribbon when we went fishing by the canal so that they'd know it was us and that we were the real right sort and be nice to us.

So you've made another lot of friends,

Said mother.

First the railway and then the canal.

Oh yes,

Said Bobby.

I think everyone in the world is friends.

If you can only get them to see,

You don't want to be unfriends.

Perhaps you are right,

Bobby,

Said mother.

And she sighed.

Come on,

Chicks,

It's bedtime.

Yes,

Said Phyllis.

Oh dear,

And we went up there to talk about what we'd do for Perks's birthday and we haven't talked a single thing about it.

No,

We haven't,

Said Bobby.

But Peter saved Reginald's life.

I think that's about good enough for one evening.

Bobby would have saved him if I hadn't knocked her down twice,

Said Peter.

Loyally.

So would I,

Said Phyllis,

If I'd have known what to do.

Yes,

Said mother.

You've saved a child's life.

I do think that's enough for one evening.

Oh my darlings,

Thank God you are all safe.