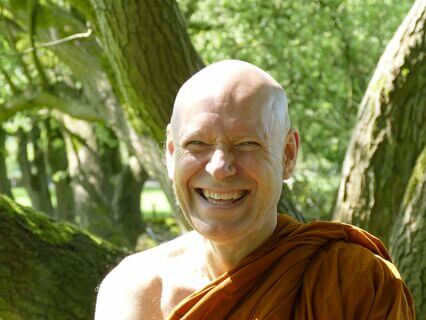

Benefits And Pitfalls Of Renunciation | Ajahn Brahmali

Ajahn Brahmali shows us how we can give up our endless search for sensory stimulation and find pleasure and peace in being helpful, kind and finding joy in meditation instead. In this way renounciation is not a chore we have to do, but rather something we enjoy and can find real satisfaction in. Ajahn Brahmali, a senior disciple of Ajahn Brahm, is an exemplary scholar, meditator, and much sought-after teacher. He has a gift for bringing the Buddha’s message to life.

Transcript

Now,

The topic for today's talk is about the benefits and pitfalls of renunciation,

And this was a topic that was suggested to me,

I'm not sure if the person who suggested it is here today,

But never mind,

That's how it often goes.

But it's a nice topic,

And it is a focus on things like the monastic life,

The monastic life is often what we think of when we think about the idea of renunciation,

But the monastic life is really just a particular expression of that renunciation,

It's an outward or external expression of that,

But of course the real renunciation is a mental thing,

It's about giving things up mentally,

And that is what then actually is the path of practice,

And that sometimes is expressed in monastic life.

So I'm going to talk a little bit about the monastic life,

What are the benefits of the monastic life,

I don't know if any of you are interested in that,

Maybe you will be interested after this talk,

That's kind of the idea,

See what happens.

And also some of the dangers,

Some of the pitfalls of monastic life,

Because not everyone thrives in monastic life,

And it's important to kind of try to understand why that might be the case.

And then I'm going to talk a little bit more about the general idea of what renunciation actually means.

Now the first thing I want to just briefly address,

And that is the thing about the word renunciation itself,

I don't know about you,

But to me the very word renunciation sounds a bit forbidding,

You know,

Renouncing means like forgoing something,

It means like giving up something,

It means like depriving yourself of something,

Right?

And sometimes when we hear about the idea of renunciation in certain traditions or certain religions or certain whatever,

It is almost like you give things up,

But you don't really expect anything in return,

It's kind of the giving up for the sake of giving up,

Maybe because something is considered bad or whatever it might be.

So the word renunciation sounds a little bit dark,

And it sounds a little bit like we are not really,

We wonder why we should renounce.

But in Buddhism,

Actually the word is actually a very positive word.

And the Pali word is the word Nekamma,

And the word Nekamma quite literally,

It means like non-sensual or non-sensory,

Non-sensory is maybe even better.

Because it is about the idea that you are kind of letting go a little bit of the world of the five senses,

That is kind of the point of this.

And of course,

The Buddhist teaching is such that when we let go of one thing,

Especially when we let go a little bit of the sensory world,

There is an alternative that arises in its place.

And that is really the critical issue.

So it's not giving things up for the sake of giving things up,

It's giving things up for the sake of aspiring to something greater,

Something larger,

A greater kind of expansion of consciousness,

Or a joy in the mind,

Or a sense of peace that comes from giving up the restless search for ever more sensory,

Attractive things,

Etc,

Etc.

So the idea of giving up the sensory world is a very,

Very positive thing in Buddhism.

And it's conjoined with all of the positive sides of renunciation.

And this has very practical consequences.

One thing that it means is that we should always,

When we do try to renounce things,

We should do all of that renunciation in a very balanced way.

We should not renounce without feeling that we have some return from that renunciation.

So really,

The process of renunciation should be almost like an organic process,

Something that grows by itself,

Just by practicing these teachings and kind of using these teachings in the right way.

And when it is an organic process,

You will find that you live your life well,

You live with care and kindness,

You have a degree of generosity in life,

You enjoy doing service for other people,

You sit down in a meditation and you start to get some peace,

You start to get some joy coming up in your meditation.

And of course,

When that joy comes up,

You start to understand that one of the reasons is because you have given up something else,

You gain something in return.

And then the idea of renouncing even more kind of becomes natural,

Right?

Because it's actually,

You understand the joy of renunciation.

Renunciation is great,

It's the best thing that ever happened to you.

The rest of the world thinks renunciation is for foolish people,

But you know it's exactly the opposite.

Renunciation is actually for the people who have some understanding of spirituality in a deeper sense.

So actually,

It is a very,

Very beautiful thing and we should not be put off by the word renunciation.

It is really just in English that this word can have,

Not always,

But can have a negative connotation.

In Pali,

It just means non-sensory or non-sensual and it doesn't really have any negative connotations at all.

If anything,

It's positive.

So what does this mean from a monastic point of view?

Why is monasticism a kind of renunciation and what are the benefits of that kind of renunciation?

And maybe also what are some of the pitfalls of the renunciation of becoming a monastic?

And of course,

When you do become a monastic,

You are giving up quite a lot.

And this is precisely the reason why the monastic life is the ideal way of practicing the Dhamma.

Because when you become a monastic,

When you live this kind of life,

You are approximating to the life of someone who is fully enlightened or fully awakened.

The monastic life is about giving up certain worldly pleasures and certain worldly attachments.

And it's quite close to the ideal of those people who have gone a long,

Long way on the path.

If you look at someone who is a noble person,

An Arya or whatever,

Someone who has the full insight into these teachings,

They will want to live as monastics because that is the natural expression of awakening.

Awakening is expressed through the monastic kind of lifestyle.

And so you will see in the suttas,

In the word of the Buddha,

The Buddha says that if you actually do achieve awakening,

You can no longer live as a lay person.

And the reason is because you don't attach to kind of houses and storing up things and having a larder full of food and these kind of things.

You don't work like that anymore.

So the moment you become awakened,

At that moment you also become a monastic in your heart at the very least.

So this is expressed,

And this is why one of the very important reasons why the monastic life is so powerful,

Because it approximates this ideal of what it means to be awakened.

In a sense,

You are trying to live that life directly and thereby renounce more things and thereby having success on this path.

But there is much more to the idea of monasticism.

This is kind of the kind of broad outline of why it works so well.

But I want to talk about some of the simple things that make monastic life very attractive.

And one of the most important things that makes monastic life attractive is all the kalyāṇamittās you have,

All the good friends,

All the spiritual companions that you have on the path.

Here at Bodhinyana Monastery,

We have over 30 monks now,

30 monks,

Right?

It's a really large monastery,

And not so far,

Just on the other side of Perth,

We have the nuns' monastery with about 15 nuns.

So 15 nuns,

Over 30 monks.

We have a couple of small monasteries as well,

Kind of in the area with two or three monks here and there.

It's a very large kind of community.

And of course,

All of these monks,

All of these nuns are heading in the same direction.

So you have all these kalyāṇamittās,

And when you meet with each other,

You tend to talk about the Dhamma,

When you see them,

You know,

Wow,

It kind of reminds you of Buddhism when you see another monastic,

Right?

You see the robes,

You see the shaven head,

You think,

Oh,

I'm one of these two,

Okay,

I better do the right thing or whatever.

It kind of reminds you of these things all the time.

So it means that you are leaning towards the Dhamma so much more easily,

Because you have these kalyāṇamittās there.

But more important than just having kind of a variety of kalyāṇamittās,

Who are on various stages of the path,

If you end up in a really good monastery,

You end up with teachers who exemplify the Dhamma,

Who exemplify what it means to be a monastic.

And I feel incredibly fortunate to have a teacher like Ajahn Brahm.

You all know Ajahn Brahm,

And I was always inspired by Ajahn Brahm from the very beginning,

Because when I saw Ajahn Brahm,

I saw someone who was a real,

Who was a Buddhist in the full sense,

Someone who exemplified the practice,

Someone who was living the teachings,

A living example of what the teaching looks like from outside when it has been internalized fully.

That's what it looked like to me when I met Ajahn Brahm.

And it is this beautiful feeling when you are around a person like that,

It's a beautiful and wonderful thing.

And Ajahn Brahm often says that most of the Dhamma happens by osmosis,

And this is true.

So when you sit together with someone who is very peaceful,

Someone who has a lot of kindness,

Someone who has this vibe,

The juju,

The juju is the modern word for vibe apparently,

Has this vibe about them that they kind of feel kind of the Dhamma in their presence.

And this is a very,

Very beautiful,

And you can just sometimes you just sit there,

And you feel peaceful,

You sit there,

And your mind turns from worldly things to Dhamma things just by being in the presence of a person like that.

And this is one of the very powerful things about being a monastic,

Which actually is much,

Much more difficult to get in lay life.

In fact,

In lay life,

It is,

You can get it sometimes,

But it is very much,

Much more hard.

And I do not wish to kind of say anything bad about the lay people,

There are some very impressive lay people in the world,

But lay life is much more busy,

But many more things going on.

And for that reason,

It is much more difficult to get access to these kinds of things.

So the idea of Kalyanamitta is an incredibly good reason to become a monastic,

Yeah,

If you ever,

If you,

If there's no other reason,

That is plenty good enough to enter the monastic life.

Because the whole Buddhist path starts with right view,

It starts with having a degree of faith in these teachings.

And of course,

That comes from these people who are your Kalyanamittas,

These people who are the Aryas,

The noble ones,

It arises from them.

And so that contact with that sort of people is incredibly important for that reason.

So this is one of the beautiful things about the monastic life.

Another kind of very powerful thing about the monastic life is that the circumstances that you are in as a monastic,

If you are in a good monastery,

Are very conducive to the practice.

In Bodhinyana Monastery,

Every monk has a little hut in the forest.

And when I sit in my hut,

I don't see anyone else,

All I see is kangaroos and birds,

Kookaburras,

The Australian laughing bird,

And I see the grass and the trees,

And I have a beautiful view from my kuti,

I even have this enormous view,

You will be surprised that people pay millions to get this kind of views that I have from my kuti,

And I just happen to have it.

Why?

Because I'm a monk.

Benefits of being a monk,

Hidden benefits.

But the main purpose is that you are secluded,

And you are away from the world.

You have animals around you,

You have nature around you,

All of these things are a great aid to calming down and to be peaceful.

You come out of the city,

You come out of the towns,

You come out of all the sensory realm,

And you kind of sit in your little kuti away in the forest.

It's a very,

Very beautiful thing to have that ability.

But what is also very powerful about that thing is that while you sit in your kuti and you meditate away happily,

The meal comes in cars from the city,

People drive all around out of Bodhidharma Monastery,

And then when I come out of my kuti,

All that food is kind of offered to the monks,

And then we get this beautiful meal every day,

365 days of the year.

That is such a,

Not only is it kind of wonderful to have that kind of support,

But it's actually very inspiring to see how the Buddhist community works together.

The idea of sitting in your kuti,

People bringing all of these things for the monastics,

It's very heartwarming and it's very inspiring to see the kindness,

The generosity,

The service of the entire Buddhist community looking after you in this way.

And you cannot avoid,

You have to feel a sense of gratitude for these people,

Because it's so beautiful.

And of course then you also want to do something in return,

You want to provide a service in return.

That of course is the idea of teaching the Dhamma to the world when you do this.

So it's a lifestyle that brings out the best in people.

When I am with lay people,

I always feel that lay people are incredibly kind to me,

Incredibly respectful and all of these kinds of things.

It's very different in lay life,

People are not going to be always so kind to you as they are in monastic life.

And it's a wonderful benefit to have this affection and kindness from people around you all the way around the world.

Whenever I travel anywhere,

Whether it's to the UK or to anywhere in Asia or anywhere in Europe or North America or whatever it is,

It is always the same.

People are very,

Very kind and they treat you with a lot of generosity and service and these kinds of things.

And it's a beautiful way of seeing the best in humanity.

There is a lot of beauty in human beings.

Sometimes we just see the negative thing,

There's a lot of good qualities in human beings around the world.

And it's wonderful to be able to tap into that and see that this is one of the wonderful things you see as a monastic.

So these are some of the things about being a monastic that makes monastic life incredibly powerful and very,

Very different in many ways from lay life.

And anyone who has a little bit of inclination to monastic life,

I would really recommend you to try it out.

Go to a good monastery.

Go to a place where you feel inspired by the teachings,

Inspired by the people.

Stay there for a while,

Feel the atmosphere,

Try to figure out,

Maybe this is something for you.

Why?

Because if you don't try it out,

You may be wasting a massive opportunity to make incredibly fast progress on the spiritual path.

Don't waste that opportunity.

This is the life.

This is the only life you've got.

Maybe you have more lives in the future,

But basically you don't know what's going to happen.

Now is the opportunity.

So now take this opportunity and make the most of it.

So I really recommend the monastic life at least,

But you have to be careful as well because sometimes people are too idealistic or they go about it the wrong way.

So how should one go about the monastic life?

What are the pitfalls?

What are the dangers in doing this?

One of the dangers is that you follow your intellect rather than following your heart.

Follow your heart when it comes to monastic life.

It is very important that when you come to a monastery that you feel right.

It feels right to you.

It feels good.

You feel at ease.

You feel a sense that there is harmony there.

It's a place where you can feel happy.

It's a place where you can easily meditate for yourself.

You feel that people are kind and caring in the right way.

This is so important because if you don't feel at ease in a place,

If you don't really relax,

If you don't feel that people are your friends,

It's going to be very,

Very hard to practice the path.

If you feel uptight or you feel people are a bit harsh or maybe they can even be abusive,

It happens in monasticism as well that there is abuse going on.

It happens everywhere because monasticism is just a reflection of the broader society.

If you have that in society,

You're going to have it in monasteries as well.

Be very careful.

Follow your heart.

If a place feels right,

If the teachings feel right,

If the teachings accord with the suttas,

You feel good in that place,

That is probably the place where you should go.

Too often,

People follow their intellect.

They have this idea,

If I go to this monastery,

I want them to practice these particular rules.

They have to practice really strict rules.

I want to see some serious ascetic practices.

I want people to be told off when they do bad things and these kinds of things.

If you come from your intellect and you have very stringent ideas of what a monastery should be like,

But you don't follow your heart,

Very likely you actually end up being disappointed.

In reality,

There's going to be a little bit of intellect,

A little bit of heart,

But make sure that you enjoy the place.

Otherwise,

I can almost guarantee that your monastic life is going to fail.

This is the first thing.

The second thing that really matters for a monastery is to work.

Ideally,

You have some good meditation before you enter the monastic life.

It is not absolutely required.

The most important thing is to have faith,

Have confidence in the Buddhist teachings.

If you have that faith and you have that confidence,

Then the meditation will happen down the road anyway.

You'll be fine.

It's going to work out one way or another.

You don't have to be too concerned.

But it is important when you come to monastic life that you don't suppress things.

Sometimes people suppress things in their character.

They may suppress desires,

They may suppress ill will,

They may suppress character traits that you feel are not appropriate in the monastic setting.

That is really the worst thing that you can do,

Because if you suppress things,

Really it will come back and bite you at some stage later on.

Very often,

That very suppression means that you're not able to make progress on the path.

Suppressing things is always a bad idea,

So it's important to be in a monastery where you can be yourself,

You can be at ease.

Yes,

There should be a degree of restraint,

But there should not be suppression.

I've seen this happening for very many monastics.

They go into a very tough environment,

And they suppress things in their character,

And after five years,

Ten years or whatever,

Things kind of erupt.

When they erupt,

In no long time,

They disrobe and they're out of the monastic life.

This is sometimes called spiritual bypassing,

Where you bypass real issues in your life that actually need to be dealt with,

Maybe psychological or sides of your personality that you haven't really dealt with properly,

And maybe you become a monastic precisely because you don't like that side of yourself or something,

And then you end up actually causing problems and causing trouble for yourself because you do that.

These are some of the pitfalls.

One of the very important ways of avoiding these particular pitfalls is actually when you enter the monastic life,

And this is also true for lay life in a sense,

Is to ensure that you are making progress in your practice.

This is one of those beautiful sayings by the Buddha,

Which always kind of inspired me.

Very often,

We tend to be a bit spiritually materialistic.

We have this idea that we want to attain certain stages or certain states of meditation.

Have you got a jhāna yet,

Or what is happening in your meditation,

And these kinds of things.

But this is not really what the path is about,

Because you can have an attainment,

You can have a stage,

But very often,

If you get that attainment,

Then it may stagnate afterwards.

If it stagnates afterwards,

What's the point of that attainment?

The Buddha says that it is not the attainment in itself.

The attainments are,

Of course,

Important in a certain way,

But what is the most important thing is that you are making progress.

That is what really matters.

When you enter a monastic life,

One of the great pitfalls is that somehow you lose sight of this idea of making progress,

Or you get trapped into various projects or various kinds of things.

The moment not making progress on the path,

That is when the path becomes meaningless.

As long as you're making progress,

There's a feeling that you are going somewhere,

There's a feeling that you have a purpose,

There's a feeling that the path is working for you,

And that is so incredibly important.

And if you do that,

Then you have a sense that monastic life is worthwhile.

The moment you stop making progress,

Even if you have a jhāna state,

Even if you have some very profound meditation,

Chances are that eventually you will disrobe,

Because the whole path becomes meaningless as a consequence.

So focus on progress in your meditation.

Focus on overall progress on the path.

Are you becoming more mindful?

Are you becoming more gentle?

Are you becoming a more caring and compassionate person in the world?

Do you feel that your samādhi is coming together?

Is your ill-will going down?

Are the kind of excessive greed,

Are they going down?

And if you see this kind of progress in your life,

Then you are on the right track,

Especially if you are a monastic.

This is incredibly important,

Otherwise the monastic life is completely meaningless.

So this is the idea of monasticism and why it is so important.

And as I said initially,

Monasticism reflects the highest ideal of what the Buddhist path is about.

The highest ideals of the Buddhist path are about giving up,

Letting go,

And this is what you are reflecting by living the monastic life,

Ideally when the monastic life is well-lived.

It is not always well-lived,

But when it is well-lived,

That is what it does.

But as I said initially,

Of course what we are really doing is that we are actually,

When we are renouncing,

It is actually a change in mentality that really what renouncing really is about.

And one of the kind of initial phases of the idea of renunciation is the idea of living a moral life,

Living a life of service,

Living a life of generosity.

And I would really recommend you,

If there is one thing I would recommend you that is going to be incredibly supportive for your entire spiritual life,

Career,

If you like,

Call it a career,

It is the only career worth having is a spiritual life,

Right?

So forget about all other careers,

Just move on to the spiritual life straight away.

So if you are going to have success in your spiritual career,

The one thing that I would really recommend you to do,

Try to live a life of service.

If you can live a life of service where you always try to implement the ideas of morality,

Of kindness,

Of care,

Of compassion,

Of understanding in everything you do,

You are going to have an incredibly successful spiritual life.

When I say service,

I mean this in a very broad kind of sense.

I mean this in a sense of looking after the physical needs of other people,

Also yourself of course,

Doing this based on compassion,

Based on understanding.

I mean using your speech as a gift to other people with a sense that you want to offer them something beautiful through the way you speak and the way you are.

This is kind of a life of service when you offer your speech to other people.

Very simply by being generous and kind in your daily life and kind of always being open to help,

Always being able to serve in whatever way you can.

And when that attitude starts to go,

It's established in you,

The attitude of service.

It's a very,

Very beautiful and powerful mind state.

That mind state of serving actually gives rise to so much joy and happiness within you.

The person who gains the most from the service is not always the recipient.

Very often it is actually the service provider themselves.

It's a very beautiful and spiritual kind of mind state.

And one of the things that always struck me in the suttas,

The word of the Buddha that I thought was very interesting,

Was that some of the words that are used in the suttas for generosity are also the words that are used for enlightenment,

For awakening itself.

Similar kind of vocabulary.

I always thought this is so fascinating.

How can the simple act of being generous,

How can the simple act of caring for someone else,

Giving something of your own,

How can that be akin to awakening?

Awakening is kind of the end of the path.

Generosity is often considered the beginning.

Of course,

It's the beginning only in the sense that you start out being generous at the beginning,

But actually generosity goes with you all the way to the end of the path.

But the idea is that when you are generous,

You are letting go of something.

You are renouncing something.

You're giving something which belongs to you,

Which is part of yourself,

Part of your identity,

Part of what you take to be mine.

And of course,

When you are giving up something which is part of your identity,

That identity of course,

From a Buddhist point of view,

Is an illusion anyway.

It's not really losing anything.

All you do is gaining something.

But when you are doing that,

That is akin to awakening because awakening itself is also giving up your sense,

Your full sense of identity that you have within.

So generosity is like leaning in the same direction.

Being kind,

Living a life of service is leaning in that same direction,

Leaning in the direction of awakening.

So this in itself is an aspect of this whole idea of nekama,

Of giving up,

Of letting go,

Of renunciation itself.

It happens in this way,

Starting with such simple ways on the path.

And then after this very simple start of the idea of renunciation,

Then comes the renunciation in meditation practice.

If you want to have real success in your meditation practice,

You are going to have to let go a little bit of your attachment to the sensory world.

You will start to understand that once you meditate,

Once you get a little bit of insight into how the process of meditation works,

It won't be long before you start to understand that there is a hindrance there,

There is a problem that if you hold on to the five sense world,

Meditation will be blocked to a certain degree.

Because the five sense world is always about the world out there,

Whereas meditation is about going within.

And if you are attached to the idea of going out into the world,

There is no way you will be able to stay within.

So there is a natural opposition between the five sense world on the one hand and meditation on the other hand.

And you start to see this in your meditation.

You start to see that the more you let go of the five sense world,

The more peaceful you become,

Because that world is so agitated,

That world is so restless,

That world is always moving around,

Going from one thing to something else.

But the world of meditation is the exact opposite.

And you start to see this opposition between the two,

And you start to want to renounce the world of the five senses.

You become less interested in it naturally.

But even though you do become more interested in it naturally,

Sometimes we can help the process a little bit.

We can kind of add a little bit to the process.

One of the things that we can do is do some of these beautiful contemplations that the Buddha talks about in the suttas,

That shows us the disadvantages of the five sense world.

And I love to talk about this,

It's one of my favorite topics,

Because it is so beautiful when you start to understand what is going on.

But just to give you a very,

Very quick reminder of some of these ideas.

One of the ideas is the idea that the five sense world is like you are a dog with a bone.

When the dog eats the bone,

It never gets any satisfaction.

All it does is kind of get the taste of blood on the bone,

But there is no satisfaction there.

And the five sense world is like a dog with a bone,

There's no real satisfaction.

Where do you find the satisfaction?

In meditation practice,

In renunciation.

Isn't that the great paradox?

You find satisfaction in renunciation,

It's kind of weird.

It sounds like the opposite of satisfaction,

But no,

It actually is about satisfaction itself.

And then there are other similes about the idea of the borrowed goods,

The five sense world,

We only have it for so long,

Then we have to give it up.

The simile of the dream,

It's like a dream world,

We're always thinking about what we want to get out of this five sense world,

But it never delivers on its promises,

Etc,

Etc.

There are a number of other similes as well,

And I would really recommend you to look into those.

So this is how renunciation works.

Renunciation is beautiful,

Because renunciation gives you access to something very,

Very interesting,

Very profound,

And very meaningful in life.

This particular meaning that you get through meditation practice,

This is where you start to feel that life has a real purpose,

Has a real aim.

It's not just about going around in circles,

Never going anywhere.

And the final act of renunciation is the act where we let go of the sense of self.

And the sense of self is this very thing that is so dear to us,

It's the ego,

It's how we relate to the world around us,

It's a feeling of something very,

Very close to us.

And it's very difficult for us to understand that this is actually a problem.

This causes so much suffering in the world,

The sense of self.

We have some idea,

Because we can see how the sense of self often leads to arguments,

It leads to opposition between people,

Because we cannot let go of our ideas or whatever it might be.

But it's difficult to let go of that.

But the final act,

Which comes at the very,

Very end of the path,

After you renounce the interest in the five sense world,

When you get into some very,

Very deep meditation states,

You come out of those meditation states,

And you realize the emptiness of all phenomena,

The idea that everything is just constructed in the world,

It is made up,

Nothing is really lasting,

Everything comes from cause and conditions.

When you get that insight into the natural reality,

And you're able to see that the sense of self itself is a construct,

It is not a reality,

At that moment,

That is when you do the final and the biggest renunciation of all that.

And what is the result of that renunciation?

The greatest bliss that you ever,

Ever had in your entire life,

A massive bliss that lasts maybe for days afterwards,

Because it is so powerful.

And that is the renunciation of giving up the sense of self at the very,

Very end of the Buddhist path.

And this is what you have ahead of you.

This is where this path is going.

It really is just a matter of implementing these ideas.

And as you can see,

The idea of renunciation from the Buddhist point of view is incredibly beautiful.

And you just start to take the baby steps,

Starting out with living a life of service,

Of kindness,

And all these kinds of things.

Then you get into the meditation,

You renounce more of the world,

And finally you get the wisdom,

The insight,

Which is the final act of renunciation.

And that is where the path comes all the way to the end.

And you will be a very,

Very happy person,

Or maybe non-person,

After that.

5.0 (10)

Recent Reviews

Ravi

October 22, 2024

Excellent talk on the 5-sense world. Progress is the path. Progress is attainment. Let go, let go and let go

Maaike

September 29, 2024

Very good clear teaching🙏