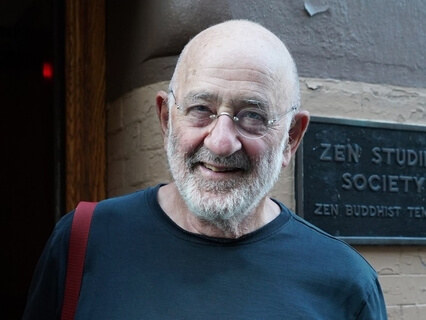

Lawrence Shainberg - Staring At The Wall With Samuel Beckett and Norman Mailer

by Tricycle

Writer and longtime Zen student Lawrence Shainberg joins Tricycle Editor and Publisher James Shaheen to discuss his new book, "Four Men Shaking: Searching for Sanity with Samuel Beckett, Norman Mailer, and My Perfect Zen Teacher." They talk about Shainberg’s struggles as a practitioner and an author and how he brings them together in his new memoir, which recounts his conversations with his literary heroes, Samuel Beckett and Norman Mailer, along with his teacher, Roshi Kyudo Nakagawa.

Transcript

Hello and welcome to Tricycle Talks.

I'm James Shaheen,

Editor and publisher of Tricycle,

The Buddhist Review.

Our guest this episode is writer and longtime Zen student,

Lawrence Schoenberg.

His new book,

Four Men Shaking,

Searching for Sanity with Samuel Beckett,

Norman Mailer,

And My Perfect Zen Teacher,

Is his second memoir about his Buddhist practice.

In this work,

And in our conversation,

Schoenberg grapples with what he considers the inherent incompatibility of Zen practice with his craft as a writer.

Zen emphasizes the unadorned present,

While memoir writing,

On the other hand,

Preoccupies itself with the overthought complexities of the past.

As the title of his book suggests,

Schoenberg tries to navigate this apparent contradiction by reflecting on his conversations with his literary heroes,

Samuel Beckett and Norman Mailer,

Along with his teacher,

Roshi Kyoto Nakagawa.

Schoenberg finds that the solution to his dilemma is elusive,

If it exists at all.

But while he may not have all the answers,

He has some pretty great stories about two of the last century's most renowned writers,

Their thoughts and misunderstandings about Buddhism.

Lawrence Schoenberg,

Thanks for joining us.

Thank you for having me.

You know,

So much is going on in this book,

You bring together your teacher,

Kyoto Nakagawa Roshi,

Norman Mailer,

Samuel Beckett,

Yourself.

What's going on here?

What brought this all together,

And what was the impetus behind the book?

Well,

What got it together was my desire to do another memoir,

A continuation of Ambivalent Zen,

And bringing to bear on that all my experience.

One never knows when you're dealing with a memoir if you're ever going to get another chance.

So it's just dealing with the amazing good fortune I've had to know these people who fed into my practice in one way or another.

Okay,

Well,

Let's go to the two of them.

I mean,

Aside from your teacher,

We've got Norman Mailer and Samuel Beckett,

Two great literary figures who are also your friends.

And I just want to quote something that you write,

Mailer and Beckett were all about form.

Beckett fought it,

Mailer embraced it,

But different as they were,

They were locked in the same dilemma.

Can you talk a little bit about that dilemma?

It seems to be one you shared.

Yeah,

Well,

I think anyone who attempts to be a writer and a dharma practitioner is going to deal with the same dilemma.

As a writer,

You are beholden to your dualistic mind,

And as a dharma practitioner,

You're in some way investigating it,

Challenging it,

Or attempting to transcend it.

So anyone who's a writer and a dharma student is going to be dealing with the dilemma that I talk about throughout this book,

I think.

Yeah,

You know,

I wonder if—I'll skip ahead a little bit—I wonder if that mirrors in some way this sort of odd paradox in Zen that you've got a tradition that focuses on transmission outside the Scriptures,

And on the other hand,

It's a tradition that has generated this immense body of literature.

So you've got the same thing going on in the tradition in a way,

Is that fair to say?

No doubt.

The literary tradition of Zen and the practice of Zen are not necessarily coinciding at all times,

You know.

We're always trying to transcend the tradition as well.

Right.

Well,

When you talk about Mahler and Beckett,

You were their friend and you had conversations with them,

And you keep coming back to associating each with emptiness and form.

You associate Mahler more completely with form and Beckett with emptiness,

Yet neither was a Buddhist.

Do you want to talk a little bit about that?

They both were interested in Zen and questioned me about it.

Mahler challenged me about it a lot more than Beckett did,

But both of them were aware of sitting meditation,

Of course,

Because as writers,

They had to be.

Don't write professionally without sitting and looking at the wall a lot.

But Mahler was ardently committed to form,

To objectification,

And he was a great journalist.

Some people think he was an equally good novelist.

I don't.

I thought he was a great journalist and not such a great novelist.

But Beckett was aware of the paradox that we're talking about as well,

But much more explicitly because he once called writing disimproving the silence.

So he was always challenging the paradox.

I don't think Mahler was.

He was aggressively involved in form and beautifully.

So that's why he was such a genius as a journalist.

What drew me to both of them was that my own work and my life was completely involved with the same dilemma that they were.

So I found it's like both of them existed in my mind,

And I had to deal with that.

Right.

So in other words,

They both existed in your mind as polarity,

So to speak,

The very tension that you discuss in your own attempt to write the memoir,

They kind of embody.

Is that right?

Yes.

The memoir actually parallels the writing of itself.

If you're the meeting with Roshi at the very beginning of the book occurs when I'm actually working on this same book.

So that's the conceit of the book,

I think,

That it tries to bring the parallel,

The writing of itself into the book.

But of course,

The memories of Beckett and the memories of Mahler were available to me in a different way.

Right.

Before we get back to that,

I just wanted to ask about the fourth of The Shaking Men,

Your teacher,

Kyoto Nakagawa Roshi.

And as you say,

The whole story is set against your last sashin with him.

Sashin for our listeners who don't know is a Zen retreat.

How did that crucible of the retreat become the backdrop for this?

How did that happen and how did that work?

Could you clarify the question?

Yeah.

Well,

As you say,

Throughout,

You keep referring back to your last sashin with Kyoto Roshi.

And I'm wondering how that sort of functioned because you're having these conversations or you're returning to these memories of Beckett and Mahler and you cut then to retreat and your struggle and retreat.

You know,

You sit on your cushion,

You sit on your cushion,

Particularly for an extended period of time.

The dilemma that I'm talking about becomes very intense and very clear.

In this particular session,

It came to a greater clarity and that conclusion of that session and the conclusion of this was what drove this book forward.

As you know,

I think it was the urgency of writing this book and the struggle I was going through that sort of made the conflict more intense and helped me to confront it a little bit better.

Right.

I mean,

Is it fair to say that the book itself is in so many ways about writing itself,

The whole writing process?

Because you know,

You consider that writing,

Which is bound by language and caught in the past,

You conclude in the book at different points that it's incompatible with Zen practice and therein lies the struggle in part.

So could you talk a little bit more about that?

Yes,

I think you're right to say it that way.

It is incompatible with Zen practice,

But that incompatibility is exactly what makes it so compelling to me and I think to a number of other writers and some wonderful writers like Merwin,

Like Matheson.

They were wonderful writers who were also serious practitioners,

But certainly there's nothing that I'm aware of that they were not.

You're dealing with something that is basically incompatible,

But you could say that it's a koan.

It's the koan that we're all dealing with.

Right.

So it's sort of fair to say that that koan or that incompatibility or that paradox is the energy that drives the whole process.

Is that right?

Oh,

Definitely.

Yes.

Okay.

So I want to add something else.

You mentioned other writers,

But one of the things that's so distinctive about your writing and your books,

Especially in this and in Ambivalent Zen is your sense of humor.

I mean,

You know,

I laughed out loud in several places and certainly in Ambivalent Zen I laughed throughout.

Can you talk a little bit about the humor?

I mean,

The self-consciousness is sometimes very humorous,

But there seems almost an intentional or perhaps a natural release in humor when you're in the crucible like that.

What role does humor play?

Well,

You know,

There's nothing more dangerous than talking about humor and making it self-conscious.

But you could say that humor is itself the inverted koan.

It's the same koan.

It's the relief from the koan.

And it was the way I found relief anyway.

When I'm lucky,

I can find my way to humor.

When I'm unlucky,

I find my way to nothing but darkness and paralysis.

So I don't think it's possible to talk about humor with any great clarity,

But it's certainly for me,

It's been the relief of the work altogether.

Yeah,

Well,

We don't get very many Buddhist books that are full of humor,

At least contemporary Buddhist books.

So I really appreciated that.

I know you don't see much humor in the Zendo.

In all the years I've been practicing,

I've heard only one person laugh aloud the whole time I was in the Zendo.

So it does not exactly encourage immediate comedy,

But you know,

The koan are very funny themselves.

Right.

Maybe you could pass out your book at the next sashin.

You hear a little bit of laughter.

I don't know if it would be appreciated,

But it wouldn't be beyond me.

You know,

One thing I have to say is that,

You know,

You're dealing with these two highly literate men in the book,

Conversations You Had With Him,

Memories of Your Life With Him.

And at the time the book was written,

As far as I can tell,

Your teacher was still alive.

And one of the questions I have,

You know,

You reproduce his language,

It's broken English,

It's terse,

It's not,

You know,

He's not loquacious as far as I can tell.

It's an interesting third poll because you have these two intellects who write copiously,

You are considering emptiness and form throughout the book.

And then you have this teacher who seems taciturn,

I'm not sure,

But for whom language is very limited.

Was that on your mind at all?

Of course it was,

Yes.

His language was,

Well,

His language is always very challenging.

And he himself sometimes celebrated his insufficient English,

But it was always a problem.

Yeah,

He once said that he had written one poem and in summer it's hot and in winter it's cold.

That was the limit of his poetic production.

But also I should tell you that when a Japanese translator was going to work on ambivalence Zen,

Kaz Tanahashi was going to attempt to translate it.

He said that the difficulty was that if you translated Roshi's English into Japanese,

It made him sound either ignorant or like a baby.

And so it's a very interesting linguistic issue we're dealing with here.

Right.

I was curious about that because three of the shaking men of the title are you,

Beckett,

And Maylor.

And then the fourth is this person whose English is limited but who seems to be really in many ways so central,

Seems to anchor the book.

Is that right?

Yes,

No question.

I mean,

His language is as much a bottom line as anything in the book,

As you know.

He has the last word in the book as far as I'm concerned.

And how would you describe that last word?

Well,

His answer to me in terms of shaking,

The shaking that I was experiencing at this particular moment in Seijin,

Which was close to epileptic,

It was a complete collision of all my struggles in the practice.

And it had led to this neurological issue,

I think.

And when I was very interested in,

I mean,

When it ceased after,

It only lasted about three minutes,

But it was,

I think,

Easily the most terrifying experience I've ever had in Zen.

But I was very clear almost immediately about the narrative associated with it that I had gotten to understood too much and it threatened my ego,

Threatened my identity.

And that was a kind of a neurological resolution of that.

When I went in,

I was very anxious to tell him that.

And when I did,

I told him that that's why I had been shaking.

I understood my shaking.

And he said,

Shaking is your true home.

And that was the resolution,

That was the sentence that drove this whole book.

Right.

It's interesting.

I think the word shake or shaking doesn't occur till the end of the book.

I mean,

Of the four,

You seem to be the one who actually shook.

I know,

I know.

I was,

You know,

That was the issue.

That was finally a resolution that he offered me.

It was,

As you know,

It's the last sesshin that I did with him.

He died just a few months later.

Yeah,

You do talk about Maler at the end of his life and you lost your teacher shortly after that sesshin.

So there is some talk about end of life issues in the book and how you saw,

For instance,

Maler at the end of his life.

He had a bit of a diminished presence,

To what extent is the book also dealing with the end of life?

Well,

I knew both Maler and Beckett around the same age that I was as I was writing the book that they both died at 85.

You know,

They were both dealing with aging and in their own way,

Both in extremely graceful ways,

I thought.

I learned a lot from them about that,

But the issues of,

You know,

Aging is just the ultimate koan,

Isn't it?

And so it certainly relates to my practice.

It relates to what I'm talking about throughout the book.

Right.

Okay,

I just want to ask a little bit more about Maler and Beckett.

They both seem to have misunderstood some aspect of form and emptiness.

I mean,

They serve as foils for the two.

But how did they understand that and how did they not understand it?

Because it's interesting.

It seems in many ways to run through their work,

And yet they were almost willfully dismissive of Buddhism.

Is that right?

I would say that Maler was,

I don't think Beckett was.

Maler loved argument above everything else.

So he loved to argue with me.

That was the basis of our friendship.

He just,

He said himself that sometime at his age,

At that point in his life,

Argument was the best exercise he could get.

So he argued,

I mean,

He loved to argue about Buddhism.

But finally in the end,

If you remember in the book that he did with Michael Lennon about the conversations on God,

He was not too far from an understanding of the Dharma.

He was not too far from placing it,

Understanding it in terms of what he called the ineffable,

The inability to describe.

So I think that Norman was much closer to Buddhism than he would ever dare to acknowledge.

Yeah.

Why don't you tell us that story of how he ended up referring to emptiness as the ineffable.

You had a conversation with him.

He said one thing,

And then something altogether different appeared in print.

Do you want to tell that story?

Yeah.

I mean,

It was hard to get to a serious conversation between us because we often drank together and he was very witty and he would take over conversations.

But in this case,

He asked me about,

All right,

What's really a definition of emptiness?

Do you have a definition of emptiness?

And I gave him the best one that I had ever heard,

Which was Bernie Glassman Roshi's description of it,

And it's not the absence of content,

But the absence of description.

And that really interested Mailer.

I think it interested him a lot.

It surprised him about how compelling he found it.

But at the same moment,

He said,

That's pretty interesting.

He said,

I've got to take a piss.

I'll talk about it with you when I get back.

And that was the last time we talked about it.

But then it did appear in this book he did with Lenin at the very end when he talked about Buddhism as a search for the ineffable,

Which is ineffable means inability,

The lack of something that cannot be described is ineffable.

So Mailer was closer to it than he would ever acknowledge.

And I think it was my shortcoming that I never got to that point of confronting it with him at that.

I could never take the confrontation far enough to confront it that way.

That was very clearly put,

So thanks.

But you describe a scene with Beckett when he was asked about Buddhism by the wife of one of his production assistants on Endgame.

And would you mind reading his response?

Not about Endgame.

Not about Endgame.

That was about the play that he did called Act Without Words.

And that was a wonderful exchange.

Act Without Words,

As you know,

Is a mime play of a person who is in a hot desert setting,

Reaching for a glass of water that continually rises above his reach,

But rises out of reach.

I'm sorry.

A chair is put there.

He stands on the chair.

The glass of water rises again.

So at the cast party that I attended after the rehearsals for Endgame ended,

A puppeteer did a version of this play,

Of Act Without Words.

It was perfect.

It was beautiful.

And the puppeteer's wife asked Beckett,

She was a Buddhist,

And she said that as long as they had been working on this play,

She had always wondered if the man had arrived at a Buddhist understanding because finally he stops reaching for the glass.

Even though the glass appears,

He just stops reaching for it.

In other words,

He's free of desire.

So she says,

I've always felt that that was a Buddhist breakthrough because he's given up desire.

And Beckett said,

Oh,

No,

He's finished.

That's funny.

Yeah.

It's funny,

But isn't it particularly clear that Beckett was,

You see,

He was a writer to the very end.

And so was Baylor.

That was what they shared.

They both committed to language.

And so Beckett said without writing,

There was no hope.

There was no reason to go on for him,

Even though he himself called it disimproving the silence.

Right.

Right.

So like when he says he's finished,

What do you think he meant?

I mean,

In other words,

He's disagreeing with her entirely.

The man is not at peace.

He is not liberated.

There is no resolution.

But on the other hand,

Like Beckett does at least have a sense of humor.

I mean,

Again,

Humor has some value or some compensatory value.

More than just having a sense of humor,

I think he could well be the funniest writer in the English language.

Right.

To me,

He is.

Yeah,

That always strikes me.

And I think likewise in your work,

Humor has that redemptive value as well.

I hope so.

Yeah,

It certainly does.

I mean,

The issues that are being dealt with and the despair and darkness on the other side of it basically beg for humor,

I think.

Thank you.

But what do you do if you can't laugh at it?

What do you have that you're finished?

Well,

Precisely.

And this guy's finished.

Yeah.

You're listening to Tricycle's editor and publisher,

James Shaheen,

In Conversation with Lawrence Schainberg,

Author of Four Men Shaking,

Searching for Sanity with Samuel Beckett,

Norman Mailer,

And My Perfect Zen Teacher.

If you're interested in learning more about Buddhist teachings in Tricycle's online classroom,

You can now join Stephen and Martine Batchelor for a six-week exploration of secular Dharma,

A novel way of rethinking the Dharma in an age of global modernity.

The course starts November 4th,

And Tricycle podcast listeners receive a special $25 discount when they enroll with the code TRIPOD25.

Enroll now at learn.

Tricycle.

Org.

Now let's return to James Shaheen,

In Conversation with Lawrence Schainberg.

Did you ever have,

I mean,

Other conversations with Beckett about Buddhism during your interviews with him or your discussions with him?

Not enough.

Not enough.

I was wary of making the practice self-conscious,

You know,

Bringing it to bear with him.

The absence of self-consciousness is exactly the point of the practice,

So I didn't want to bring it up too much with him.

But he more than once asked me if I was still looking at the wall.

He said,

What are you doing when you go to what he called a Buddhist place?

And I said,

Well,

We just sit and look at the wall.

And of course he said,

I've been doing that,

You know,

For 50 years.

But whenever we met again or sometime by mail,

He would say,

Are you still looking at the wall?

But that was pretty much the end of it.

Yeah,

I think in an essay you wrote,

He says something to the effect of why would anybody go to a place to do that or something like that.

I don't remember,

But it was very funny.

He asked me,

Well,

What do you gain?

What do you go there for?

What are you looking for?

Tranquility or?

And I said,

No,

Equanimity in its absence.

And that was impressive to him.

I have to say,

It was impressive to me too.

I had never said any such thing before.

Well,

Maybe that was the lack of self-consciousness.

Yeah.

You hang out with a guy like that,

He's going to make you a little bit more eloquent than you naturally are.

Yeah.

I mean,

Speaking of which,

I mean,

Your friendships with both of these people is interesting in and of itself.

I mean,

The book is great and bringing them into it with your teacher is an amazing read.

But you know,

Mailer wasn't the easiest guy.

And I imagine that at times you might've been intimidated by him.

I don't know.

But you know,

He's notorious for his misogyny,

His violence.

He was such a provocateur.

How was that?

I mean,

Actually,

When I was putting him in the magazine,

One of the staff was a little bit chagrined that Norman Mailer should appear in our magazine.

I,

On the other hand,

Pretty much separate out all of the criticism of him from his writing,

Which I think is pretty brilliant.

How was the friendship with him?

Well,

I was very lucky.

I met him when he was 75 years old.

Right.

And by that time he had mellowed considerably.

And his body had betrayed him in a lot of ways.

He had serious arthritis.

He had breathing problems.

He had dental problems.

He was hard of hearing.

But he was aging in a very graceful way,

I thought.

At that point in his life,

I think it's fair to say that the priority in his life was friendship.

And he was just an amazingly good friend.

And he was extremely generous with me in every way.

And I think with a number of other young writers,

He could be very generous.

So I know women who can't believe that I would even write about him or that I would even have consented to have a relationship with him.

But they didn't know him as I did.

It was quite amazing the way he was aging.

He said,

I once quoted to him Philip Roth's statement that old age is a massacre.

And he said,

You know,

It's not that disagreeable.

He said,

It's nice to be able to go into a bar without having to square your shoulders.

Yeah.

I mean,

It's as opposed to Woody Allen,

Who humorously,

Perhaps not humorously said,

There's nothing at all redeeming about old age.

I know.

I know.

And Mailer was always surprising me.

Well,

You know,

One time he said he was having trouble with his work,

He said he couldn't sleep.

He had been watching too much television.

You know,

He says,

I did not writing at all.

He said,

If I weren't so old,

I'd be depressed.

That's funny.

So just back up for a second.

Tell us how you met Mailer and how you met Beckett,

Because it seems pretty serendipitous.

Yeah,

Well,

Both were just great strokes of luck and both a result of giving them my book,

Requesting them to read.

I had always sent Beckett my work early on,

Just out of homage.

I had sent him my work without any introduction and I never had an answer.

Of course,

I'd send a care of his publisher and I sent him the book I did on neurosurgery,

Which was,

You know,

Pure journalism.

And I,

It was called brain surgeon.

I expect that I had no chance of hearing from him in response to that either.

But within 10 days,

I had an answer from him with a great appreciation of the book.

It turned out that almost anything about the brain was interesting to him.

It was just a great stroke of luck that I sent him that book.

And of course,

And as I quoted the response,

His letter to me,

He said,

I've always believed that here in the end is the writer's best chance,

Gazing into his synaptic chasm.

That was his first note to me.

Wow.

You must have been pretty shocked that you got a response.

Shocked?

Yes.

I don't know how I could ever describe the shock.

I mean,

That I didn't faint on the spot is a kind of a miracle,

But I just took me some time to figure out the return address on the envelope because his writing was very small.

But yeah,

It was a tremendous shock to me.

And so how did it go from there?

I mean,

What was the next step?

Well,

Immediately.

Then I wrote him and asked him if I could come and meet him sometime.

And again,

I didn't expect an answer.

And again,

He responded.

You see,

I think I was just lucky and this was a point in his life when he was open to younger writers and open in general.

But anyway,

He wrote to ask if I was going to be in Europe anytime soon and it turned out that I was going to be doing publicity for that book on neurosurgery in London at a time when he was going to be directing a production of Endgame.

So he asked me to meet him at that time.

I mean,

He just asked what hotel I would be staying at.

And the day after I got there,

He called me at the hotel.

And what about meeting Mailer?

Well,

Mailer was years later.

I gave him a copy of Ambivalent Zen in hopes of getting a blurb.

I had very little hope when I gave it to him.

I knew him just superficially around Provincetown from a few social encounters,

But I had no reason to expect that he would be interested in me or interested in a book on Zen.

A week later,

He called and invited my wife and I to dinner.

And we went to his house where I sat at a big table,

About I think 12 people at the table.

If he didn't mention my book until the very end,

He pointed at me and he said,

This guy's wrote a pretty good book.

I'll tell you why I like it because it shows me why I've always hated Zen so much.

Well,

That's very nice.

That's good dinner table conversation.

You know,

They were both strokes of amazing luck,

Right?

Why that had ever happened cannot be explained otherwise.

But your friendship with Beckett was much longer,

Is that right?

Yes.

How old were you when you first met Beckett?

When I first met him,

I was around 50.

And it was several years later that you met Mailer?

Well,

Quite a few years later,

You know,

I was in my late 60s when I met Mailer.

Right.

So how do these two influence your work or how have they?

I mean,

They must have influenced your work before you even met them,

But was meeting them,

Did that deepen the influence or change how you looked at writing?

I don't know that it did.

The influences were very,

Very deep from the start.

You know,

Beckett had been my deity as a writer for many years and then and Mailer,

My deity as a journalist.

And you know,

The great irony is that the book that I sent Beckett,

The brain surgeon,

Was very much influenced by Mailer,

By armies of the night.

I think that helped me write that book more than any other.

And they were,

As you know,

They were completely different.

They were antithetical as writers.

That antithesis existed within me as a writer.

So what about now?

I mean,

Does this dilemma continue?

Are you continuing to write?

Does the same dilemma figure into the same extent it did in the book that you just wrote?

Or have you taken a break?

I'm trying to take a break,

But I'm not very good at it.

What does that mean?

Are you?

Well,

I'm yeah,

I'm writing.

I'm trying to,

I'm trying to write more.

To tell you the truth,

I'm trying to write about my dog.

I'd like to write a biography of my dog if I could,

But a lot of people,

As you know,

There's a vast literature on dogs.

I think we talked about Jay Ackerley's My Dog Tulip,

Didn't we?

We have,

We have.

It's one of the great ones.

Right.

I'm reading now a book called The Difficulty of Being a Dog.

That is,

I recommend to anyone who's interested in this subject.

What's it called?

The Difficulty of Being?

The Difficulty of Being a Dog.

It's more of an investigation of the treatment of the dog in literature.

It's extremely interesting and moving.

Right.

A mutual friend of ours laughs about how much we actually talk about our dogs.

I mean,

Isn't it pretty amazing how close you can get to a dog?

Oh,

It's astonishing.

It's a kind of intimacy that I've never known before.

I've never known it otherwise.

And well,

My dog died about six weeks ago.

I'm so sorry to hear,

Larry.

I'm sorry to hear about that.

Yeah,

I'm still dealing with that primary grief.

Oh boy,

I'm so sorry to hear.

I know how much you love that dog.

I love mine too.

I'm sorry about that.

Of course,

You know that you take on mortality when you take a dog on,

Their lifespan is short.

Right.

But the intimacy,

You know,

The grief you feel when they're gone is proportionate to the intimacy you knew when they were alive.

You know,

It's inexplicable that she's gone.

Yeah,

Yeah.

I lost a dog early on and I certainly know that.

In fact,

The dog I have now has the same name.

So these 50 years later,

I would say.

Okay.

Is there anything else you'd like to say about the book?

I did my best with it.

You know,

I hope I serve the practice because that's the whole point of it.

Yeah,

I thought it was a great book.

I'm recommending it to our readers and congratulations.

It's really a fantastic book.

Well,

Thank you so much.

I appreciate your interest in it and I appreciate your having me here.

Okay,

Thanks so much,

Larry.

Thanks again for the invitation.

Sure.

Thank you.

Bye bye.

Bye bye.

You've been listening to Lauren Schoenberg discuss his new book,

Four Men Shaking,

Searching for Sanity with Samuel Beckett,

Norman Mailer,

And My Perfect Zen Teacher here on Tricycle Talks.

If you'd like to hear more episodes,

Visit us at tricycle.

Org slash podcast.

We'd love to hear your thoughts about the podcast.

Write us at feedback at tricycle.

Org or leave us a review on your podcast player.

Tricycle Talks is produced by Paul Ruest at Argo Studios in New York City.

I'm James Shaheen,

Editor and publisher of Tricycle The Buddhist Review.

Thanks for listening.

4.8 (21)

Recent Reviews

Debra

August 23, 2019

Fascinating and insightful discussion! Thank you for sharing this. Namaste