Arun Gandhi: The Gift Of Anger And Other Lessons From My Grandfather Mahatma Gandhi

by Tricycle

“Anger is like electricity: it is just as powerful and just as useful, but only if you use it intelligently.” So told Mahatma Gandhi to his grandson Arun Gandhi, who lived with the political and spiritual giant on his ashram between the ages of 12 and 14. In our latest podcast, Tricycle's executive editor Emma Varvaloucas sits down with Arun to discuss the lessons that he’s learned from his grandfather about working with anger and cultivating peace.

Transcript

Welcome to Tricycle Talks.

I'm James Shaheen,

Editor and publisher of Tricycle,

The Buddhist Review.

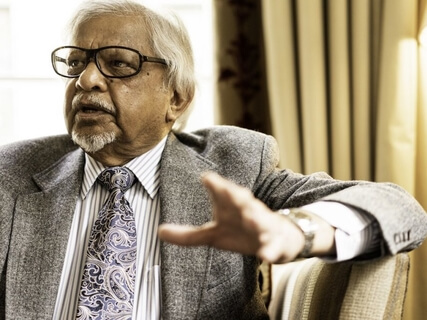

We're here today with Arun Gandhi.

He's the grandson of famed Indian political and spiritual leader Mahatma Gandhi.

Arun spent two years as a young teenager at his grandfather's ashram,

And it was there that he was shaped by the values Gandhi is best known for.

Respect,

Understanding,

Acceptance,

Appreciation,

And compassion.

These are values sorely missed in today's world,

Especially in our current climate,

Where more often than not we give into suspicion,

Distrust,

And fear.

Arun Gandhi has a new book out,

The Gift of Anger and Other Lessons from My Grandfather.

In it,

He advocates for a way of being in the world that comes from a place of love and trust.

As an author and activist,

Arun himself has spent his life following in his grandfather's footsteps.

He's here today to speak with Tricycle executive editor,

Emma Varvaloukas.

So thanks for being with us here today,

Arun,

And welcome.

Thank you very much for having me on the show.

So I know you spent a couple years with Gandhi on his ashram when you were younger,

When you were about 12,

Right?

Could you give me a little bit of description of what it was like to live with him?

Well,

It was a very unique experience,

Largely because he was a great figure.

And I really didn't know how great he was until I came and lived with him.

And I would see hundreds and sometimes thousands of people outside early in the morning,

Just waiting to get a glimpse of him,

And then they would go about their work.

And that's when I realized that he was,

You know,

Honored by everybody.

And so I used to bask in the glory,

Enjoy that part of it.

It was also different because it was a very simple lifestyle.

And we had some very interesting experiences.

The week we arrived at the Sevagram Ashram,

That whole week,

We had nothing but boiled saltless pumpkin and dry bread for all our meals every day.

On the third day,

My younger sister,

Six years old,

She got fed up of this.

And she said,

This is nonsense.

I'm going to go and ask grandfather why this is happening.

And she just barged into his room and she said,

You know,

I think you should change the name of this ashram.

Instead of Sevagram,

You should make it Kola Gram.

Kola is the Indian word for pumpkin.

Pumpkin ashram.

Yeah.

So he asked,

Why do you say that?

And he says,

Well,

Ever since we came here,

We're eating nothing but pumpkin.

And I'm fed up of pumpkin.

Why can't we have something else?

That was the first time he realized that this was happening.

And so that evening in the prayer service after that,

He called the manager of the ashram and said,

This is the complaint I received.

Is it true?

And he said,

Yes.

And so please explain why do you do this?

And he said,

Well,

We are following your advice.

We are eating simple food that is grown on our farm.

So grandfather said,

When I said what is grown on the farm,

That doesn't mean we grow only pumpkins.

We can grow so many other vegetables too.

The message I got from it later on is how dogmatically people would follow his advice and not give any thought to it.

And so it was a very interesting experience.

But I think it was more interesting for me because I had this background in South Africa and I had this physical beatings,

First by whites when I was 10 years old and then by blacks,

Both the times because they didn't like the color of my skin.

I was filled with rage and I wanted to fight back again.

And that's when I was taken to India and left with grandfather.

And the first lesson he taught me was about anger,

Understanding anger and being able to use that energy intelligently and constructively.

He used the analogy of electricity.

He said anger is like electricity.

It's just as powerful and just as useful,

But only if we use it intelligently.

But it can be just as deadly and destructive if we abuse it.

So just as we channel electrical energy and bring it into our lives and use it for the good of humanity,

We must learn to channel anger in the same way so that we can use that energy intelligently for the good of humanity rather than abuse it and cause violence.

And then he explained to me how we need to have a stronger mind.

We pay a lot of attention to physical strength but not to mental strength.

And we assume that because we read and we study and so on that that is enough mental exercise.

But that's not exercise.

It's just filling our minds with knowledge.

What we need is exercise to be able to control our minds,

Not allow it to run amok as it happens.

Normally because we haven't done this exercise,

We'll find that there are about 10,

12 different thoughts racing through our mind at the same time.

And to that extent,

We are distracted always.

So we can't pay full attention to what is going on at this moment.

So he made me sit in the room and hold in front of me something that gave me pleasure to look at.

It could be a flower or a photograph or something and then focus on that object for one minute and then shut my eyes and see how long I could hold that image in my mind's eye.

In the beginning,

I found the moment I shut my eyes,

The image vanished.

But when I began to do this regularly,

I could keep that image longer and longer in my mind.

And to that extent,

My mind was coming under my control.

So if you have a strong mind,

Then you don't flare up when you are provoked into anger,

Which is happening now.

You know,

We get angry and we just blow up and say things and do things that sometimes changes the course of our lives completely.

And I think that was a very powerful lesson because today,

Harvard University has found that more than 80% of the violence that we experience in our personal lives or in the lives of our nations is generated by anger.

People just get angry and they blow up and say things and do things that ends up in more and more violence.

So the idea is that you're not a slave to the great intense emotion when it comes up.

Is it then you take a step back and assess the situation or what's the next step after that?

Yeah,

The next step is you assess the situation.

You know,

He also asked me to write an anger journal.

He said every time you get angry,

Don't act on it,

Don't say anything unless you have an immediate peaceful response to the thing.

Take time out and write a journal,

But write the journal with the intention of finding a solution and then commit yourself to finding a solution.

And that was very important because a lot of people do write anger journals now,

But it hasn't really helped them because they just pour their anger out into the journal.

So every time they go back and read the journal,

They're just reminded of the incident and they get angry all over again.

So we don't want the journal to be a reminder of the incident.

We want the journal to help us find an adequate solution to it.

So he wouldn't necessarily be an advocate for maybe venting to people just to get rid of the energy of the emotion.

It would be to actively trying to figure out how to solve it.

Exactly.

Getting rid of the emotion doesn't help.

Then you face that issue again and again over and over.

So it's important that we try to find a solution to the problem and put it behind us instead of leaving it hanging in the air to come back again and haunt us.

And your book in particular,

It's called The Gift of Anger.

What would be the gift of anger in all of that?

I think anger itself is a gift.

It's a motivating factor.

I even go to the extent of saying anger to the human being is what fuel is to the automobile.

If we don't put fuel in the automobile,

It's not going to run.

And if we don't have anger within us,

We won't do anything.

We'll just lay back and be content with everything.

So anger is a motivating factor.

It's a wonderful thing.

The tragedy is that we end up abusing it instead of using it intelligently.

So it's interesting for me to hear because in the Buddhist tradition a lot,

We think about anger.

Definitely it can be a motivating force,

But one that's so often poisonous that it's a motivating force that it's better to find actions being motivated by compassion,

Which can be similarly energetic.

How do we make sure if we do feel ourselves motivated by anger,

Maybe to correct injustice or something like that,

That it's not then poisoning our actions in a way that our actions and our behavior is angry?

Well,

We have to make that conscious effort,

Learn to control our minds and be able to channel our minds into finding adequate solution to the problem.

Then we won't let it fester within us.

We would be able to use that energy properly.

I had a very interesting experience which happened in 1969 when I was living in India.

I was forced to live in India because I got married to an Indian woman and the South African government wouldn't allow me to bring her back with me.

So all of these prejudices that I suffered through the 23 years in South Africa,

All the humiliation of being judged because of the color of my skin,

And finally culminating in not allowing me to bring my wife back to my birthplace.

So one day I got a letter from an Indian friend who was coming out of South Africa for the first time and he was a little nervous and so he asked me if I would receive him in Bombay and make arrangements for his travel and stay and all that.

And because he was a good friend I said,

Okay,

I will do it.

And he came by ship.

In those days,

Because the Suez Canal was closed,

All the passenger ships from Europe were going through the Cape.

And so he hopped onto one of those ships and came to Mumbai.

And the ship arrived late in the night and I was the first Indian to get on board.

And before I could meet my friend,

I ran into a strange white man who just grabbed hold of me,

Shook my hands and introduced himself as Mr.

Jackie Besson,

A member of parliament from South Africa.

And the moment he introduced himself,

I immediately realized who he was.

He was a member of the nationalist party.

He was very vocal in his prejudices.

He supported apartheid.

And in many ways I held him responsible for all the humiliation that I experienced there.

So my immediate reaction at that moment was to insult him and even toss him overboard.

Exactly.

Toss him overboard.

But then I realized that my parents would never forgive me if I did that.

And so instead of insulting him,

I shook hands with him and I told him that you are a guest here and I will do my best to make your stay as pleasant as possible.

But I want you to know that I am a victim of apartheid.

I am forced to live here because your government won't allow me to bring my wife back.

But I'm not holding it against you.

I'm going to forgive you for that.

And then during the next four or five days that the ship was in town,

Every day from early in the morning till late in the night,

My wife and I would take them around,

Do all the touristy things,

Shopping and sightseeing and whatever they wanted to do.

And during that time,

We also as friends talked about apartheid.

I would express my feelings.

He would try to justify it to the extent he could.

But it was a friendly dialogue.

And every time the dialogue got a little bit touchy,

We would just talk about something else.

I didn't expect this.

On the last day when we went to say farewell to them and wish them bon voyage,

Both of them,

Husband and wife,

Embraced us and wept tears of remorse.

Tears were streaming down their cheeks.

And they told us,

In these few days,

You opened our eyes to the evils of apartheid.

And we are promising you that we are going to go back to South Africa and fight apartheid.

I was still a skeptic at the time.

And I wasn't willing to accept this.

So I told my wife,

I said,

Let's wait and see.

You know,

These people have a habit of coming out of the country and saying one thing.

And when they go back into the country,

They resume their old habits.

So let's see whether he really means this or he's just saying this to make us feel good.

We followed his political career for the next four or five years.

And we found that he had changed completely.

He was such an outspoken critic of apartheid that he was thrown out of his party.

He lost his elections,

But he didn't give up speaking against apartheid.

And that's when I thought,

You know,

If I had given into my initial reaction of wanting to throw him overboard and insult him,

He would have just gone back as a confirmed racist and think,

You know,

These Indians deserve what they get.

But just by interacting with him as a friend and treating him as equal and being nice to him was able to change his entire outlook.

So that is the power of nonviolence.

If you approach the situation through love and respect,

We can find a solution.

If we approach the situation with anger and hate,

It's just going to mess up everything more.

So one thing I thought was really interesting about that story is the way you described how you went about the friendly dialogue with him that at any point,

If it got a little bit too touchy,

You kind of just backed off.

Right.

You know,

In certain circles today,

There's a cry that you should really call people out at all times if they do something that's offensive or that's considered to be wrong in whatever respect.

Do you have any thoughts about that?

Well,

I do believe that we should call people out on when they do something wrong,

But it should be done in a kind,

Respectful,

Friendly way,

Not accusing the people,

Not being aggressive about it.

Today,

In many situations,

We are very aggressive.

Even when we are pointing out somebody's mistakes,

We do it very aggressively.

So it's all about how we approach people.

Sometimes truth can hurt badly,

But if it is said kindly,

It can be a very good way of transforming people.

It's that idiom that it's not what you're saying,

It's the way that you're saying it.

Exactly.

You know,

Just to circle back to your time at the ashram with your grandfather,

I was wondering if you could tell us any other lessons you learned from him or what it was like to deal with him interpersonally just as a grandfather.

Well,

He was a very loving grandfather and very approachable,

Which was something I was admiring.

I still admire very much that in spite of his busy schedule and you know,

All these worldly things that he was involved in at the time,

He was willing to spend one hour with me every day.

And exactly at three o'clock,

He would leave whatever he was doing and come and sit with me and just be a grandfather,

You know,

Help me with lessons if I needed any help or he would talk to me or tell me stories and,

You know,

Just be a grandfather.

And during that time,

We also did spinning,

You know,

He was into spinning cotton all the time and he was a great multitasker.

Even before we had discovered the name multitasking,

He was doing it in those days.

He said,

Well,

We are talking,

We should use our hands to produce cotton.

The reason for this was he felt that there were so many poor people living in India who didn't have enough money to buy clothes because what Britain was doing was taking Indian cotton away to England,

Processing it into clothes and bringing it back and selling it at very exorbitant prices.

And poor people couldn't afford it.

So they used to be half naked all the time.

And grandfather said that political freedom will be meaningless as long as they are economically subjugated.

So we need to give them the means.

And every member of the family spent a few hours every day spinning and producing the cotton threads.

They could make their own cloth and not have to depend on British goods.

That was a very important thing because I think in many ways that was the turning point.

The spinning of cotton really broke the backbone of the textile industry in Britain.

And in 1931,

When the British government organized a roundtable conference,

By then there were many millions of Britishers who were unemployed because the textile industry had to close down because of the boycott that Gandhi had started in India.

And so when he came to London for the roundtable conference,

The British had organized a lot of security and had arranged for him to stay in a very secure place.

And when he saw this,

He said,

No,

I don't want all this security.

I want to go and stay with the workers in their neighborhood and be their guests.

And the British government said they'll kill you.

They're so angry with you,

They'll kill you.

So he said,

Well,

If I'm to die,

I'd rather die at their hands.

But I would like to go and live with them.

And he went there with an open mind and he embraced them and showered them with love.

And he told them,

He says,

I sympathize with your state of affairs,

But I want you to know that there are nearly 150 million people at that time in 1930s,

150 million people who are in worse situation than you are with poverty.

And I have to think about them.

And they understood.

They in return embraced him and loved him and showered him with a lot of love and respect.

So he was able to transform even those angry people into becoming friends and supporting his cause.

And I think it was all of those pressures that eventually made the British government give freedom to India.

You know,

Those kinds of stories are simultaneously very inspiring to hear and also very depressing because it feels today sometimes that people like Gandhi were an anomaly and that a lot of the people involved in politics and just the political climate and the landscape in general,

Particularly in the United States right now,

Just feels completely devoid of love,

Compassion,

Respect.

Yeah,

Well,

You know,

Gandhi believed that because we have to sustain a materialistic lifestyle,

They want to keep producing more and more things and keep selling more and more things.

And he said to sustain the materialistic lifestyle,

We have to create a whole culture of violence.

A culture of violence over the years has seeped so deeply in us that everything we do,

Our language,

Our sports,

Our entertainment,

Our relationships,

Everything about us is violent.

And in that kind of violent atmosphere,

We can't really create peace.

So the only way we can create peace is by dismantling that culture of violence and introducing the culture of nonviolence.

Our culture of violence depends on fear.

The more fear you can put in people,

The more control you have over them.

And that's why we build so many weapons of mass destruction and armies and all that kind of thing,

Because we want to put fear in our enemies,

So-called enemies.

We do the same thing at home with our children.

When we threaten our children with punishment if they don't behave,

We are controlling them through fear.

And they,

Because they are afraid of that,

They submit quietly to it.

But in a culture of nonviolence,

It is not through fear that we control people,

But through love and respect.

So the culture of nonviolence tends to bring out all the good and the positive things in human beings,

Whereas the culture of violence brings out all the worst things in human beings.

When you talk about dismantling a culture of violence and cultivating a culture of nonviolence instead,

It seems like such a large and impossible project,

Especially when you're approaching it from the perspective of a single individual.

Where does,

You know,

Maybe just a person listening start with something like that?

Well,

Gandhi said we have to be the change we wish to see in the world.

It has to start with the individual.

And it's only when the individual starts changing that ultimately society will change too.

We unfortunately wait for somebody else to make the first move.

We have been shown through examples that it is possible to live a simple and yet a very comfortable life and not keep buying things and buying things and get caught in that trap of materialism.

Because materialism and morality have an inverse relationship.

When one increases the other decreases.

So the more materialistic a society is,

The less moral it is.

And we can see this in our lives here today.

To make money,

People are going to do anything.

And now we have reached the stage when people are dispensable,

Profits are not.

So these big corporations to show big profits,

They lay off hundreds and thousands of people.

And the big top bosses,

They make salaries of millions,

Whereas the workers get a fraction of it.

So this kind of immoral attitude,

Where we don't consider human beings as human beings,

But we look at them as how can I exploit you for my gain?

That is the only thing that we think about.

And we continue to exploit everybody that way.

So as long as we have that kind of an atmosphere,

We are never going to morally improve.

So we have to make a choice.

Are we going to submit to materialism entirely and forget about morality,

Then we are going to create chaos and destructive atmosphere.

But if we want a balance between materialism and morality,

Then we can find that balance.

And we can live comfortably with fewer things and be more compassionate towards those who don't have a life and create that kind of harmony between people.

Because peace today is not the absence of war.

Peace is creating harmony in society,

Where all of us can live with love and respect for each other.

I think what's frustrating for a lot of people,

And I think myself in particular,

When you hear like,

Be the change you want to see in the world.

In theory,

Of course,

I would agree.

But then when you describe this sort of economic machine that's going along,

Sort of chomping everyone to bits,

It seems like it's such an impotent response to say,

Just,

You know,

Work on your inner reactivity.

What would you say to somebody who's feeling that way?

In my opinion,

That's making an excuse for not doing anything.

It's a very interesting story.

So a millionaire,

Everything in life,

Beautiful house and servants and everything that he could want in life,

He had it,

But he was very unhappy.

He couldn't enjoy life.

He couldn't sing and whistle and be happy,

Even for a moment.

He was all the time afraid and worried about things.

He had a servant who was just mopping the floors and doing absolute manual work.

He was paid very little money.

But every day he was coming to work and he was so happy.

He was singing and,

You know,

Whistling away and being joyful.

So this millionaire wondered,

He said,

This guy doesn't have anything at all and he's still singing and being happy.

And I've got everything and I can't be so happy as him.

So he went to his psychiatrist and asked him,

How do you explain this?

And the psychiatrist said that it's because he hasn't joined the 99 Club.

He said,

What do you mean by 99 Club?

He said,

Well,

You put $99 in an envelope and leave it to him,

Put it in his mailbox,

See what happens.

Well,

When this guy gets the $99,

He starts wondering why 99,

Why not 100?

And how can I make this 100?

So he started working harder to be able to make that $99 into $100,

$100.

When he made it into $100,

He says,

Then I can make it into $110.

And so he got trapped in that making the money and he forgot about his singing and a joyful life.

And that is the trap we are all in.

We are all wanting more and more every day.

They come out with new products in the market and we must have them.

To have them,

We all want to work harder and harder and do two jobs and three jobs.

And so we don't know what we want from life.

Do we want quality of life or do we want all these possessions in life?

And sometimes it's difficult to realize that it would just be easier,

Simpler,

Better,

Just to step back,

Decide not to get caught in the trap.

It's a vicious cycle.

One thing I was thinking about in preparing for this was that Gandhi's political movement in part was so successful because there was this spiritual cohesion to it.

And when you think about political movements in the United States,

I think on the right,

You see a lot of political movements that do have in particular Christianity as the backbone and they end up being successful.

I'm thinking about the Tea Party.

On the left,

Which seems to be a little bit allergic to religion,

They don't have the spiritual cohesion.

It seems like they're often unsuccessful in their political process.

Do you think there's anything to that theory?

Well,

I would think there is some part of it is true.

I wouldn't say that religion specifically is the cause of the success of the right-wing people.

Their commitment and wanting to be focused on one issue,

Whereas in the left-wing struggles that we see today,

They really don't have any commitment.

They just want to destroy the present order of things.

They don't have a replacement for it.

One of the reasons why Occupy Wall Street,

Which was wonderful,

The way it rallied around and did everything,

The reason why,

In my opinion,

It didn't succeed is their objective was to destroy Wall Street and destroy the hold that Wall Street had on people's lives and nations' lives.

But what do you replace it with?

I mean,

You destroy something,

Then you can't just leave it in a state and give it up.

You've got to replace it with something.

And people want to know,

This is what we're going to replace it with.

Then that kind of movement will have that moral compass,

Which should come from truth.

What Gandhi did was he called his campaign Satyagraha,

Which is the pursuit of truth.

Even when he was fighting the British,

He was pursuing truth.

He was not just wanting the British to get out from there.

What is the truth?

At one stage,

He felt that the truth is the British should live in India and be equal,

Everybody should be equal.

But then later on,

He realized that that will not work.

So then he said,

Well,

The British have to leave us to our fate and we will decide whatever is going to happen to us.

And so he was perpetually wedded to truth,

Not only in his struggles,

But even his life.

And he said that a pursuit of truth should be the way of life of every individual.

We must always be honestly and diligently pursuing truth in our personal lives,

As well as in our public life.

Could you give me an example of how he pursued truth in his personal life?

Well,

He,

You know,

In his personal lives,

In his relationships with people,

In what he did with everybody,

He looked at the larger truth of the thing and how that is going to help there.

And one of the things that he came to the conclusion of is we have to build communities.

Today,

We have neighborhoods where people have come to live because it's convenient,

But there is no community.

We just go and we lock ourselves in our homes and we don't know who lives next door to us.

We don't care about them.

We are just concerned about ourselves.

And now with technology,

We have make friends thousands of miles away when we don't know who's right next door to us and we don't care about them.

So that kind of independent living that we have become so accustomed to is very detrimental.

It doesn't lead to a community.

And I will go to this extent of saying that if we are not able to build a cohesive family,

Then we are not going to have a cohesive community.

Because if a family is torn apart and there's no respect within the family for each other,

Then you can't expect those kids to respect outsiders.

So we are destroying the very fabric of society right from the family all the way up to nations.

And then we have this whole concept of nationalism and patriotism that we all harp on in every nation.

That gives us the impression that we owe allegiance only to our country.

We must do whatever it takes for our protection and we don't care what happens to the rest of the world.

Now we can be the most powerful nation in the world with all the weapons of mass destruction,

But we are not going to be safe if the rest of the world goes down the tube.

We are going down with them.

So the stability and security of any nation depends on the stability and security of the whole world.

And it's only when we have that kind of world vision,

Then we will be able to save this world from self-destruction.

Today every country's foreign policy is based on what is good for them.

And that means they are exploiting the rest of the world to gain whatever they consider to be good for them.

In that kind of atmosphere of exploitation,

We are just making more and more conflicts.

It's taking a lot of mental gymnastics for me to imagine a world in which countries were not concerned with their own well-being.

Exactly.

We have gotten so used to this and we are pumped by politicians every day that you've got to be nationalistic and patriotic and if you are not,

Then you are a pariah.

And Hindu nationalism in particular is on the rise in India right now.

Yeah,

It's everywhere.

Like here we have the right wing,

Ultra right.

In many parts of the world,

The ultra right wing is coming into power.

And that is also because the people who had been in power for so long,

They just kept on exploiting the community instead of doing something concrete for them.

The reason why we lost this last election in the United States was that the existing parties ignored the pain and agony of all the people who were thrown out of their jobs and had no alternative there.

And so many towns and cities in the country are dying because there are no jobs and there are nothing to sustain.

So Trump was able to come in and speak to those disaffected people and give them some hope and he got elected because of that.

So even today,

If these political parties don't wake up and realize that they have to do something to help the undertrodden and the marginalized people,

We are going to have chaos in this country.

Well,

You had a front row seat to the racism and economic injustice in South Africa as a small child and now you're here in the United States as an adult and it seems like the same events all over again?

Same thing going on and it's just,

You know,

We're going deeper and deeper into it.

You know,

Sometimes things seem hopeless,

But we can't afford that luxury of being hopeless.

We have to remember that all of us can make a difference and we must make that difference.

That's why I call myself a peace farmer.

All I can do is go and plant seeds in the minds of people and hope those seeds will germinate.

But I can't help them make them germinate.

It's up to them to make it happen.

I think you wrote,

Gandhi wouldn't want us to look at the world the way it is now in despair.

Yeah,

He was always full of hope and he felt that there is goodness at every human being.

You know,

That's part of the Hindu belief that all of us are equally good and bad depending on what buttons are pressed.

We are all capable of doing right and wrong and good and bad things.

And if we appeal to the goodness in human beings,

Then they can turn around and create good things.

But if we appeal to the worst in human beings and the negative in human beings,

Then we're going to get more chaos.

Arun,

Could you tell us a little bit about when you decided that you wanted to follow in your grandfather's footsteps and being,

You call yourself a peace farmer?

Well,

I think when I look back now,

I think it's something that I grew up in.

I saw my parents doing work for the poor and showing a lot of compassion.

I remember when I was a little boy,

Five,

Six years old,

And I didn't have anybody my age to play with except the children of the African agricultural laborers who lived around our ashram.

And they lived in tremendous poverty.

But I was allowed to play with them.

And I was always told that while you play with them,

You got to learn from them what do they do to entertain themselves.

They don't have the luxury of going and buying toys or the things that they need.

And I found that they would make their own toys.

So we used to go around hunting for those old discarded matchboxes and get all these shirt buttons from discarded shirts and clothes and use those as wheels.

And we manufactured these little toy mini cars and we would play with them.

We also learned to go down by the river and dig up clay soil.

With that clay,

We made human figures and animal figures and we played with that.

So it was educative as well as creative and fun.

And in return,

My parents,

When I started going to school,

They said,

Now it's your duty while playing with these kids to teach them.

Whatever you learn in school,

You teach them.

Use part of your play time to educate them and teach them.

And so I started doing that.

And that,

Of course,

Created a big kind of havoc because the word got around that I was educating all these kids,

Basically just teaching them ABC and counting and subtraction and all that I learned in school in the first grade.

I would come and share it with them.

And that word got around and very soon we had 100 kids from five miles away from our ashram coming to our place to get education.

And that's when my parents and my sisters and everybody got involved and we were running a veritable school there.

So these experiences gave me that understanding of compassion and concern.

I think this one thing led to another and I just kept going deeper and deeper into it.

What an extraordinary upbringing because most people don't have the benefit of having their family always tell you to look outward.

Yeah.

Yeah,

That was,

I think,

Something I'm very proud of.

Thank you so much for all of your insight.

It was really a pleasure to hear about growing up with Gandhi and the lessons you learned from him.

So thanks again for being here with us.

Thank you.

It was a pleasure and I hope that my sharing has led to some understanding of my grandfather's philosophy,

Make a positive difference.

Thank you.

Thank you.

That was Triscule executive editor Emma Varvaloukas in conversation with Arun Gandhi,

Author of The Gift of Anger and Other Lessons from My Grandfather,

Mahatma Gandhi.

We'll be back next month with meditation teacher Sharon Salzberg,

Who will talk to us about real love and what that means.

If you liked this podcast,

Didn't like it or anything in between,

We'd love to hear from you.

Email us at feedback at triscule.

Org.

This is James Shaheen,

Triscule's editor and publisher.

Thanks again for listening.

4.9 (171)

Recent Reviews

Kate

November 14, 2025

Wonderful. Thank you so much for this wise sharing that resonates deeply with me

Ravi

September 12, 2024

I grew up in a Gandhian household in southern India. To me there is no greater figure as a role model than the Mahatma himself. Thank you for reminding me how lucky I was to be able to appreciate that life now.

Richard

March 25, 2024

Wonderful talk, inspiring and uplifting. A genuine pleasure getting to know a little about Arun Gandhi and his life.

Fae

July 14, 2023

Beautiful sensible inspiring interview. Thank you

Carolyn

July 14, 2022

Wonderful interview, filled with compassion and gentle insights.

Heather

September 29, 2021

Very Interesting Thank You

Marlana

January 4, 2021

Wonderful interview with meaningful insights into our world and human interactions that can lead to peace and community.

Letisha

July 16, 2020

Absolutely Excellent, I Really needed to hear this Now & Often. Is there any way of sharing this interview on social media ??? There are so many people I know who would appreciate it & share it far & wide !!! Beautiful Interview, wonderfully produced. ❤🌎🕊🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟

Rohan

June 12, 2020

Like listening to Ghandi himself!

Jacqueline

June 1, 2020

I am so grateful for Arun sharing this timeless wisdom of the power of intelligent action and love for respect, equality and justice for all. Jai Bhagwan! ❤️✨❤️ Victory to the Spirit ❤️✨❤️

Saga

May 18, 2020

inspiring, a joy to listen to

Ellen

May 18, 2020

This message is very important to hear. ❤️🙏🏼

Nick

August 5, 2019

Very insightful talk. Thank you for all this - beautiful to meditate on the wisdom contained here.

Nina

August 4, 2019

Excellent interview! Inspiring to learn more- a great reminder how anger can be a positive strength if used wisely !

Catherine

August 2, 2019

Thank you🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻Interesting and educational 🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻

Marcia

August 2, 2019

.....and, so, Gandhi still lives on. I am grateful, and revived. 🙏🏻

Heidi

August 1, 2019

So inspiring, thank you!