22:48

22:48

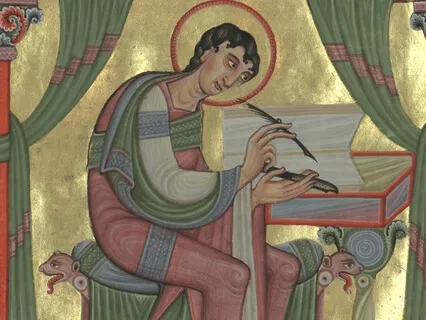

Transience In Early Medieval English

by Erin G

Rated

4.9

Type

guided

Activity

Meditation

Suitable for

Everyone

Plays

408

This guided meditation invites you to contemplate two poems from early medieval England. Read in the original Old English and in modern English translations, the poems invite us to reflect on the transience of each passing moment.

TransienceMeditationPoetryOld EnglishReflectionBreathingImageryBody AwarenessMedieval PoetryOld English LiteratureReflection On Past YearGuided BreathingHistorical ImageryModern TranslationsPoetry MeditationsTranslations