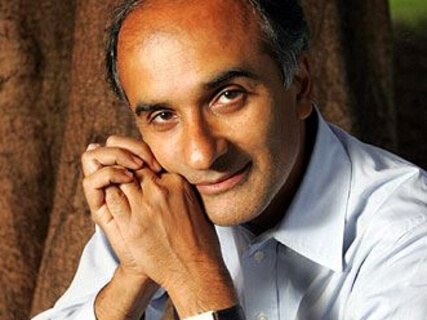

Pico Iyer: Inside Japan As An Outsider

by Tricycle

For the acclaimed travel and spirituality writer Pico Iyer, home is not such a clear concept. The first time he ever felt homesick, it was for his adoptive home in Japan. In this episode of Tricycle Talks, Iyer discusses his latest book Autumn Light, the way impermanence colors Japanese life, and what it means to try to understand other cultures at a time when the term globalist has become, in many parts, a dirty word.

Transcript

Hello and welcome to Tricycle Talks.

I'm James Shaheen,

Editor and publisher of Tricycle The Buddhist Review.

This episode I have the pleasure of speaking with the acclaimed author Pico Ayer,

Who is best known for his writing on travel and spirituality.

Ayer has written more than a dozen books,

Including two novels and a profile of the Dalai Lama.

He has written for Time,

Harper's,

National Geographic and the New York Times,

Among other publications.

Ayer was born to Indian parents in Oxford.

He was raised in England and Santa Barbara,

California,

And his work has taken him all over the world.

But about three decades ago,

Pico married and settled down in his wife's native Japan.

He has since become one of the foremost translators of Japanese culture to Western audiences.

Recently,

He has written two new books about his life there,

Autumn Light and The Beginner's Guide to Japan.

As you'll hear,

Pico views the books as complimentary.

While Autumn Light describes his experience within the culture,

The Beginner's Guide offers his perspective as an outsider.

His work reminds us of the value of trying to understand other cultures at a time when the term globalist has become in many parts a dirty word.

Pico Ayer,

Thank you so much for joining us.

I'd like to start by congratulating you on your latest book,

Autumn Light.

It's truly a beautiful read and I really hope that our readers pick it up and I'll be mentioning it again during this interview and at the end of the podcast.

So,

Congratulations.

Thank you so much,

James.

It's really nice to hear your voice and to be talking with you again.

For those of you who may not know,

Pico is one of our contributing editors and actually wrote for Triscule before I was even there.

So that's a very long time ago indeed.

I think I was in your first issue probably,

1991.

Yes,

I think that's right.

But reading Autumn Light,

It just occurred to me,

I mean,

This is a theme that seems to recur through all of your work and it's the sense of home.

You seem to always be at once at home and not at home and in this case,

In your adopted home of Japan.

I'm just wondering how you look at home and how you understand that idea.

That's a beautiful question and the last thing I expected to hear,

But you've really touched on something fundamental because I am a believer in secret homes and the way in which we can feel affinities with places even if we have no official associations with them.

Just the way you might go into a crowded room and see a stranger and feel that you know her better than the friends and family you came with.

Of course,

The beauty of the global age is we can visit and even perhaps live in the places that make deepest sense to us.

So home in that sense would not just be the place where you were born or grew up or live,

But the place that lives inside you and the place where you become yourself.

Just as you suggest,

That is Japan for me.

I've been there for 32 years now,

Entirely on a tourist visa.

I would never want to be Japanese or not even want to work or be an official part of the society.

But from the first minute I spotted it,

Which was just on an unwanted layover at Narita Airport outside Tokyo for four hours,

I felt that I understood it and it understood me.

I was very surprised just last year to speak to your question.

Somebody was saying to me in a class that I was visiting,

Well,

You've traveled all over the world and you're an Indian but you grew up in England and based in California.

Have you ever felt homesick?

And I said,

No,

No,

No,

The nature of my traveling life is never to feel homesick.

And then I said,

No,

Wait a minute,

I do.

For the first time in my life,

I do feel homesick for my adopted home.

And I realized it's become so much a part of me that now as I'm sitting in radiant springtime California,

A part of me is still just longing to be back in Japan.

It's really become as much a part of me as my breathing.

And it's interesting how you can be at home and feel at home,

Even in a place where,

As I say,

I will always be a tourist.

It's interesting that you say that because in so many ways,

You're more than just a tourist,

At least from,

Say,

My perspective as a New Yorker.

Your wife is Japanese,

Your children are Japanese,

And also you really represent a mix of cultures.

You're a Westerner,

Yet you were raised by Indian parents in both the UK and in the US.

You're both British and American.

And you've lived in Japan for the past 30 plus years.

So can you say something about belonging to multiple cultures or embodying them?

Yes.

And as I listen to you talk,

I'm thinking that in some ways,

Home is the place where all of one's selves come together,

Or as many of the different parts of oneself come together as possible.

And so it's very possible that Japan is in its way a traditional Asian culture.

So the Indian part of me feels entirely at home there.

And although my Indian mother might have once upon a time wished that I had married an Indian woman,

She feels very at home with my Japanese wife because Japanese notions of motherhood and daughter-in-lawhood are very similar to Indian ones.

And certainly,

Japan has always reminded me of England in terms of the scale of things,

The seasons,

The hierarchy,

The codedness.

They're both imperial islands that sift tea and preserve gardens and keep their distance from things.

But of course,

It's an England that's exotic and indecipherable to me.

So in some ways,

It's like an exotic version of the place where I grew up,

Which gives me a sense of familiarity,

But even more richly gives me a sense that I'll never be on top of it.

I can't take it for granted the way I might with England.

I'm not sure if it relates in any way to America,

Even though the surfaces of Japan are so American and I love going to baseball games.

But certainly,

I suppose in my life,

It speaks to this sense that we can make our homes in different ways than previous generations.

When my grandparents were born,

They were more or less given a home,

A religion,

A caste to which they belonged,

Whether they liked it or not.

And I think in the new century,

More and more of us can to some extent choose our homes,

Our communities,

Which places we feel that we have a sense of belonging to.

And that's a challenge because if you don't choose,

You end up falling between the cracks and belonging to nowhere.

But for me,

I think it's been a great blessing that I don't have to live in India or England or America,

All of which are places which I can assume falsely that I know,

But I can live in this beautiful,

Mysterious place that's always unknowable.

And to speak to the beginning of your question,

I was flattered by what you said because my Japanese language skills,

For example,

Are very limited.

But as you said,

I have been with my Japanese wife for 32 years and our Japanese kids for the same amount of time.

And I remember one of my great Buddhist teachers has been Marcel Proust.

And he said,

Because he translated works from English,

I don't really know English,

But I do know John Ruskin.

And I feel I don't know the Japanese language very well,

But I do know my neighborhood where I've been 26 years.

And I do feel I know the little bits of Japan represented by my wife and son and daughter.

Yeah,

Well,

We'll get to Japan in a moment.

In so many ways,

Japan,

Along with the season itself of autumn,

Are the protagonists in many ways.

But you're also a journalist and certainly you're very aware of what's going on in the world,

You travel.

And the very hybridity that you so celebrate really seems in some ways threatened by a resurgent nationalism that seems to be driven by xenophobia that runs counter to the fluidity of identity that you celebrate.

Would you like to comment on that?

You're absolutely right.

And I represent the sort of fortunate globalized elite probably that nationalists are most aggravated by.

And I sometimes think that nationalism,

As you said,

Is resurgent.

It's on the rise partly because it's on the run.

It feels threatened and imperiled as borders are coming down and people more and more like our last president belong to many places all at once.

But I've always had much more faith in individuals than in larger bodies such as governments or corporations.

And inevitably,

The world is never all going to be one and politicians and companies depend on a sense of difference and division for their very identity.

But I think individuals are wiser and subtler than their governments and can reach across the divisions that governments make.

And by that I mean that every day somebody around me in Santa Barbara and somewhere around you in New York or more than one person of Polish origin is marrying someone from Iran and of Rwandan origin is falling in love with somebody from Vietnam.

And when the little children of those unions arise in the world,

Suddenly another division is gone.

So I feel that human by being by human being,

The world is moving in one direction and that's towards the erosion of binaries and of simple distinctions.

And people are always going to be unhappy about that and try to fight against it.

And it's shocking and humbling to see how that has spread,

As you say,

Across the world very quickly.

But I remember how a few years ago I was in San Francisco and I met a woman and she said,

Well,

Maybe I don't think very favorably about Islam.

But suddenly my daughter marries someone from Iran and my granddaughter is half Iranian,

Belongs to the Islamic tradition.

How can I ever hate my granddaughter?

And although not everybody holds to that philosophy,

I think more and more of the world is coming to that position.

I was struck speaking of journalism that the New York Times a few years ago noted that in 1958,

2% of Americans were in favor of mixed race marriages.

By 2014,

The number was 87%.

So from 2% to 87% just in my lifetime of people accepting and maybe in some cases celebrating marriages across racial divides.

So I'm heartened by that.

Though,

As your question suggests,

We don't move in straight lines and it will never be an easy progress.

But I think of growing up in England,

London was the most boring,

Dull,

Gray city on earth.

Now it's one of the youngest and fizziest precisely because the average person you meet in London was born in a foreign country.

Most of them are not of English descent.

Same with Toronto,

Which used to be known as Toronto the Gray.

Same with New York probably quickly where you are sitting.

So we need,

Especially those of us who are in the fortunate 1% to move freely across borders need to be aware that this is unsettling to many.

And I think we most of all need to be aware of the millions who are crossing borders in much more undefended ways,

The refugees and their number is growing so quickly.

But rather than thinking about the nationalists who oppose me,

I probably would think more about the refugees who target our conscience and ask us what we're going to do about their form of multinationalism.

That's so nicely put.

In other words,

Really the genie is out of the bottle,

There's no going back and perhaps this is nationalism's last gasp.

Yes,

Or maybe not last,

But I'm sure it's going to keep gasping and grasping.

And I think it's in the nature of human beings to create walls.

And if some divisions come down,

We feel comfortable in a community,

Which means people outside the community too.

So I don't think we'll ever be without borders or divisions.

But as you were saying,

I think they're less and less relevant in people's thinking.

By chance,

I just met a friend of mine who was at elementary school with me.

And he's a very sophisticated cosmopolitan Londoner.

And he confessed that when he stepped into the fourth grade classroom in England and saw me at the age of nine in England in the 1960s,

He had never seen a dark skin.

And he's raised four daughters in London.

And he is saying that when they bring their friends home,

They don't even stop to mention so and so is from Jamaica or so and so is of Indian background or so and so is Nigerian.

As far as they're concerned,

They're all Londoners,

They're all friends.

And so just between my generation,

His generation and his daughters,

We've moved so much forward.

So I think the media loves to spotlight and sometimes to encourage the bad news in the world and we take for granted the many,

Many divisions that are disappearing every day.

Well,

Thank you.

That's a great way of putting it,

I think.

I'd like to talk about Japan now since you do live there at least half the time.

Is that right?

Yes,

As much as I can.

And in my ideally seven months a year,

So yes.

And it's so much of what your latest book,

Autumn Light,

Is about.

So would you mind reading the passage that I sent you earlier today?

Gladly.

And I think this comes very close to the beginning of the book and is in some ways setting a tone or a theme for what follows.

We cherish things Japan has always known precisely because they cannot last.

It's frailty that adds a sweetness to their beauty.

In the central literary text of the land,

The tale of Genji,

The word impermanence is used a thousand times and bright,

Amorous Prince Genji is said to be quote,

A handsomer man in sorrow than in happiness.

Beauty,

The foremost Jungian in Japan has observed,

Quote,

Is completed only if we accept the fact of death.

Autumn poses the question we all have to live with.

How to hold on to the things we love even though we know that we and they are dying.

How to see the world as it is yet find light within that truth.

Yeah,

That's beautiful.

That's what really pulled me into the book in the early pages.

But a point that you make throughout the book is that impermanence is an ever present truth in daily Japanese life in a way that it isn't so much in the West.

Is that fair to say?

It's a wonderful way to say it.

I should stress this is the first time I've ever talked about this book in public.

So it's really the first time I've had a chance to hear an outsider's response to it.

So yes,

I mean,

My first thought is that suffering,

Old age and death are the stuff of every human.

And so when I wrote this book,

I thought at some level it applies to everyone on the planet because everyone listening to this conversation is getting older by the minute,

Is seeing her parents get older,

Is watching her children grow up and maybe begin to scatter around the world.

So very much universal themes.

But you're right that Japan doesn't flinch from death and doesn't turn away from it.

And actually,

Since I completed the book last year,

My mother-in-law died in Japan and I was there when she died.

And one of the things that struck me was that the day after at the funeral,

Everyone was giving her beer,

Everyone was putting her favorite food next to her,

Everybody was talking to her.

And the dead are very much alive in Japan.

They never leave.

And famously,

In the midsummer celebration of Obon,

There were lights,

Lanterns lit all across Japan so that the departed ancestors can come and visit their loved ones for three days.

And then there were lights to send them safely on their way home again.

So that sense of living amidst the dying and therefore asking what dies and how much other people ever die is,

As you say,

Much more present in Japan than many cultures.

And I think Japan is an old weathered seasoned culture that has realized that we gain nothing by pretending reality doesn't exist.

And we gain a lot by making friends with reality,

Which is to say with death.

And I'm talking to you here in California,

Which in some ways is the home of possibility and therefore of wishing death away and doing everything you can to remain as young as possible.

And coming from California to Japan,

I always feel it's tonic that I think of Japan as an autumn culture because it's about training us to die and training us to live with the fact that the things that we care about are going to die.

So you put your finger on it perfectly.

Impermanence is universal,

But awareness of the impermanence is especially pronounced in cultures like that.

You know,

You mentioned just now a ritual around the dead.

And I know that in your next book,

A Beginner's Guide to Japan,

Which I was fortunate enough to have a peek at,

You point out that in Japan,

While one in four,

Only one in four say that they adhere to a particular religion,

A far greater number of them participate in rituals.

And this is also true in your book,

Particularly with regard to your wife,

Her rituals,

Which in some ways are opaque to you,

But in another way,

You seem to have an intuitive sense of.

Could you talk about that?

I certainly have a respect for them and a sense that grief needs a channel so that when my mother-in-law died last year,

All the rituals are quickly ensued,

The funeral rituals,

The Buddhist monk who chants,

Who comes back the next week,

Who comes back the next year.

I think that allows people to feel that they're responding to loss the way people have done for centuries.

It puts them in a larger community and it gives them something to do with their sadness or anger or frustration.

And I find in this very young culture where you and I are sitting,

That is often a challenge.

I remember my father died many years ago and I and my mother probably didn't know what to do with that,

Who to take our anger at,

What to do with our sense of sorrow.

And Japan has created this very efficient mechanism in some ways,

Emotional and you could say religious for dealing with it.

And it's interesting,

As you know,

I spend a lot of time with His Holiness the Dalai Lama and I travel with him every November when he comes to Japan.

And I remember his once saying in Japan,

Publicly I think,

That whenever he talks about meditation in the West,

Students perk up.

And whenever he talks about ritual,

They tune out.

And he said,

Isn't this interesting?

In Japan,

Whenever I talk about ritual,

Everyone's suddenly interested,

But whenever I talk about meditation,

They're much less interested.

So,

You know,

Japan famously for good ways and bad is a cradle of ritual.

But I think when it comes to death,

It's really useful to have a precedent and somebody to tell you,

These are the things to do when somebody dies.

Though to us,

Often they're startling,

Such as right after the cremation,

Everyone gathers around the bones and picks up the bones and takes them home.

So to us,

That is,

As you said,

Opaque.

But to them,

Maybe it helps with an emotional release.

You know,

One of the things that I really enjoyed the book,

By the way,

I didn't know you were such an avid ping pong player.

It's interesting because so much of the social life there,

In your social life,

Centers around the center where you play ping pong.

And it's interesting the characters you describe and it's quite poignant that even in a description or the description of those interactions,

Underneath it all,

There's this sense of impermanence that runs through it.

People come and go,

Some become sick and disappear altogether.

And yet so little is said.

I mean,

You make a lot of the very taciturn nature of Japanese social life.

Can you say something about that?

Yes.

I remember I started my book on the Dalai Lama a few years ago by saying that I had heard that Buddhism and life generally is about joyful participation in a world of sorrows.

How to bring the fact of loss together with the fact that we can find beauty and happiness in everything.

And so in this book,

Which is more or less about autumn and things falling away and leaves rusting and people getting older,

I wanted at its center there to be something to do with merriment and celebration.

And so indeed,

As you say,

Every other scene in the book is at my local ping pong club where I play three times a week with my neighbors,

All Japanese,

Most of them older than I am even in their 70s and 80s.

And one of the things I love about that is my friends in their 80s are actually much better at ping pong than the occasional teenager who shows up,

Which reminds us of all kinds of things.

Again,

That life doesn't go in a straight line,

That autumn has certain advantages,

That spring does not,

And that not everything is about decline.

Also,

My friends in the ping pong club having retired are much more full of high spirits and youthfulness actually than when they were in their 30s and 40s and caught up in the grind of work.

And I think in Japan,

It's especially notable because people's lives are so pressured between the age of let's say 30 and 65,

That when finally they retire,

They really enjoy a second childhood.

And you could say a second spring.

And the men who tend to be incarcerated in their offices for long,

Long hours,

For 30 or 40 years,

Suddenly are kids again.

They're jumping around.

They have all the time in the world.

They seem younger often than their grandchildren.

And it's a wonderful thing to be reminded of,

That autumn is the first step towards spring in a way.

And that in the midst of,

As you said,

Even in the ping pong club,

People falling away,

Disappearing,

Getting sick and dying,

There can be so much happiness.

That the fact of loss and unhappiness are not exactly the same thing.

And that actually,

I think in Japan,

People would say the fact that things don't last is precisely why we can and have to enjoy them as much as possible.

And so I feel that in a book about loss,

The core of it should be about enjoyment.

And that's partly what the ping pong players represent for me.

Yeah.

You also point out how different competition is in Japan.

You mentioned a Japanese way of being invisible,

Competing in a way that makes everyone feel like a winner,

Rather than,

And to use your words,

A soloist tootling off on his own.

Well,

James,

I'm so glad you were light on that,

Because that really is one of the central sentences and one of the central passages in the book.

So my friends here in the West are very surprised when I tell them that in the ping pong club,

We play best of two games.

So that usually there's no winner or loser.

In Japan,

When you go to a baseball game,

If the score is level at the end of 12 innings,

It ends in a tie,

Which never happens here.

Ties are actually a good thing in Japan.

And in the Japanese baseball leagues,

Because the standings are based on winning percentage,

A team with lots of ties can finish ahead of a team with more victories.

So often teams are playing not to win,

But in order not to lose.

So in the ping pong club,

Best of two games,

We switch partners after every two games.

When we're not switching partners,

There's a sort of boss of the team who subtly makes sure the very good player is paired with a not so good player so that nobody feels a loser.

And it's a cliche that we all know,

But a culture like Japan is essentially constructed around the notion of harmony.

And Arthur Kerstler delivered this wonderful line about how the Japanese have developed a competitive sense without competition.

And I think of Japan as a choir,

To speak to that phrase about soloist,

Almost as an orchestra in which each person knows her part.

She plays it perfectly and therefore a beautiful symphony comes out.

Nobody is noticing each individual part,

But if any individual part were missing,

We might well notice that absence.

And I grew up in England and this country,

Which I think of as the sort of centers of individualism.

And I was encouraged when I was at college to express myself,

To advance myself,

To stress what is unique and different in me.

And it's so tonic and perhaps educational to go to a culture where you're taught to disappear within the whole and that indeed in a choir,

There's no talk of winning and losing.

All you do is serve your part.

And I think that's an aspect of how Japan functions so seamlessly by ensuring people try whatever they're doing very hard,

But taking out the notion of competition and giving people a sense of larger responsibility.

And sometimes if people will ask me,

Why did I move to Japan?

I will say that growing up in England and the U.

S.

I learned to speak,

But I really wanted to listen.

I wanted to learn how to listen.

And Japan seemed to be the place where I could best learn that.

And in England and the U.

S.

I think I was taught to try to stick out.

And Japan was a place where I thought I could go to learn to be invisible.

And England and the U.

S.

In my colleges,

I think I was urged to succeed in certain ways.

And in Japan,

I would be eased into the notion that success is the least important thing of all.

And therefore in the ping pong club,

We'll have 15 games in the space of 90 minutes.

But at the end of the day,

I couldn't tell you if I've won or lost,

Partly because there's a constantly rotating partners.

And therefore one minute I'm winning with a very good partner.

Six minutes later,

I'm losing every game.

And that almost increases the enjoyment because well,

It's like the famous lines in the Bhagavad Gita about being completely committed to the action,

But completely detached from the result.

And I feel that Japan is a good training in that.

Yeah.

You know,

Our web editor,

Matt Abrahams and I were marveling in the office today that baseball could end in a tie.

We thought that was really cool.

But it would be fair to say,

And I think it comes through in your book,

That the higher virtue than success is harmony.

Yes.

Yes.

It's interesting to go back to baseball.

The first time an American manager,

Bobby Valentine,

Was brought over to Japan to lead a professional Japanese team,

Which is 1995.

He took this very mediocre squad and he led them to the stunning second place finish and he was instantly fired.

And certain foreign observers were taken aback.

So they went to the team spokesman and said,

What's with that?

He had such a good season.

And why did you fire him?

The answer came back because of his emphasis on winning.

So in this country,

I think winning is a good thing.

In Japan,

Maybe not,

Because as you said,

It disrupts the harmony.

And such an interesting notion that a team doing well might not be in the larger interests of the team.

Thank you.

Thank you.

Let's move for a moment into Autumn itself.

The book is called Autumn Light and the autumn seems itself to be the protagonist in many ways,

Just as Japan in certain ways is.

Can you say something about how the seasons seem to shape daily life in Japan?

Because,

You know,

I'm aware of the importance of seasonality in Japan,

But I really wasn't until I read your book aware of just how directly it influences daily life that you have even micro seasons.

Yes,

Thank you.

I really do feel that autumn is the protagonist of this book.

And about the micro seasons,

Japan,

I think borrowing is ever from China,

Sometimes says that there are 72 seasons in every year and each season lasts for five days.

And therefore seasonal food,

Seasonal clothes,

Everything that is based on the seasons changes constantly.

So talk about impermanence within a permanent frame.

Every five days,

It's regarded as the coming of a new turn in the cycle.

But that cycle has been going strong and actually providing a frame and a foundation for lives for 1400 years.

But I really do feel that the seasons are kind of religion in Japan.

And so every November,

Which is the season I write about,

All my friends and neighbors flock out into the gardens and especially the parks and the temple gardens to watch the turning of the leaves.

And November is a very radiant time,

So the skies are sharp,

Cloudless blue,

But everything that's going on under those skies is falling away and death on the coming of cold and dark.

And I think people often dress up to go out and look at the leaves.

And I feel it's almost they are going to the gardens the way people in this culture might traditionally have gone to church or cathedrals.

Why do people go to cathedrals here?

To be reminded of something higher than themselves,

To be brought together into a congregation,

To be aware of light even on a dark day,

And to be put in place in some sense,

To be reminded that the human story is just one small part of a much bigger canvas.

And I think that's exactly what's going on with the seasons in Japan.

It humbles us.

It reminds us how little we can know or anticipate or control and how we're at the mercy of these elements.

So we might as well cherish them,

Admire them and get on with them,

Which I think is exactly what Japan has refined over the last,

Again,

900 years.

And as you know,

Probably,

In Japan there's a separate word for the self that you maintain within the house from the one that you show in public.

And it's assumed that there need be no connection between who you are behind closed doors and who you are on the street.

And I often feel that cherry blossoms are the face that Japan presents to the world.

Because frothy,

Cheerful,

Young,

A little bit erotic,

Very pretty.

But really what's at the heart of Japan is autumn and that riddle of what to do with the fact of things falling away.

So I always make a point of being in Japan during the autumn.

And I think the core of Japan for me,

And of course you see it in all the haiku and most of its art,

Is this word they have monoganashi,

Which means the sadness of things.

The sadness having to do with the fact that,

As in Buddhism,

Every meeting ends in a separation,

Every life ends in a death.

But also the sadness in which we find our wonder and beauty.

My epigraph in the book comes from Emily Dickinson and because she sat still in her room for 26 years,

Almost as if she was a Zen practitioner,

I think she explains Japan often very well.

And I know at one point she said,

All we know of beauty is its evanescence.

And yet that is certainly why they cherish the cherry blossoms.

If the cherry blossoms were frothing and flattering for months on end,

People wouldn't give them a second look.

But it's the fact that they're about to be gone that makes us go out and celebrate them.

And I think that's how things are with human relationships too.

The fact that as Buddhism teaches,

The person next to me could be a skull not so long from now is the reason why I want to give her my love and attention.

You know,

Listening to you now and having read the book,

I was delighted but not surprised that you're a big fan of the film director Yasujiro Ozu.

You talk a lot about,

A few times at least,

You talk about him.

And you know,

What I took away from that is your discussion of the fact that in Japanese art and literature,

The focus is so often on the backdrop against which human drama plays out rather than on the characters themselves,

Whether that backdrop is the season,

As in this case autumn,

Or the social context,

Or the historical movements.

Those are what come to the fore.

And I think you discuss how we look at paintings,

For instance,

As Westerners,

We might look at the people in the foreground,

Whereas a Japanese might look at the background and understand things more in terms of conditions that we're subject to.

Exactly.

So if you look at any Hiroshige or Hokusai painting,

The characters are just outlines,

Silhouettes,

And what you're really drawn to is the falling snow,

The turning leaves in the background,

Mount Fuji behind,

Everything again that dwarfs us and that will continue long after we are gone.

And as for Ozu,

As you say,

He does exactly that.

One of the cardinal Japanese principles he honors is that what we don't say is probably much more important than what we chatter about.

So he has a lot of silence in his films,

Which I tried to get into this book,

And many of his most pregnant shots are of an empty room,

And suddenly everyone's left the room and he'll just stay on the empty room.

And that's in some ways where the emotion becomes overwhelming.

The rest of the time people are making chit-chat,

But it's when they're gone that you really feel them.

And so I have scenes in my book in which I return to our little apartment,

And it's when I see my wife's things and all the things in which she's invested so much hope and care that sometimes I can see her even more vividly than when she's standing right in front of me.

And I think one of the great principles of Ozu,

Which is inherent to Japan and probably to at least Japanese Buddhism,

Is the notion of nothing special.

And I think an Ozu film could be described as a film about nothing happening.

The diction is very simple.

It's just,

Hello,

Oh,

Really,

Hello,

That kind of thing.

And it looks as if nothing is happening.

And of course,

Everything essential is happening because it's in those seemingly undramatic moments that you notice in a wife's eyes that she's very frail,

And you notice the daughter is looking out the window and she's going to be gone soon.

And you notice when the neighbor comes in that something is happening next door that we don't know about.

And in some ways,

That's much truer emotionally to my experience than a Captain Marvel movie.

I've had my house burned down and me inside it and all kinds of dramas in my life.

But really,

I feel my life is composed of much smaller moments that resound.

And I think Ozu catches that to perfection.

Yeah.

I mean,

The cumulative effect of his films is so deeply moving and yet there's such an economy,

Especially when it comes to speech.

Could you say something about that economy of speech in Japanese culture?

Yes.

I mean,

I sometimes tell my friends here,

And they don't always believe me,

That I think the idea of a perfect date in Japan is you go with your sweetheart to a movie,

You take it in,

Both have very strong responses,

And at the end of the movie,

Silently go home.

In other words,

The less you say,

The closer you are.

And we don't need the chatter.

We don't need the opinions.

Again,

As you were saying,

Harmony is more important.

And that silence brings people together in a way that words so often separate.

And I think that's why Zen practice,

For example,

And so much in Japan,

Is about not speaking as a vehicle for communion,

For harmony,

For taking the static and disruption out of life.

There are two presiding spirits in this book.

One,

As you perfectly say,

Is Ozu.

And the other is Leonard Cohen,

Who of course was an ordained Zen monk for five and a half years.

And I never forget how when I would visit him,

Although he's probably the most eloquent person I've ever met,

He would often take two little chairs out into his tiny garden overlooking a residential street and a flower bed.

And we'd sit there,

And we wouldn't say a single word.

And the first time this happened,

I thought maybe he was giving me a gentle hint.

He wanted me to go home.

And I said,

Oh,

I should leave you.

You're busy.

And he looked at me searchingly,

Said,

Please,

Don't go.

And he had realized,

Thanks to his Zen practice and his Japanese teacher,

That the richest thing and the deepest thing and the most intimate thing within us that we can share is silence,

And that words are just graffiti that we draw on the surface of something much more profound.

And of course,

He was with his Japanese teacher Sasaki Roshi for 40 years or so.

And Sasaki Roshi spoke limited English.

Leonard spoke no Japanese.

And they would just have the most wonderful,

Long conversations of silence.

And Sasaki Roshi,

I think,

Once said,

Why should we talk?

That's only going to lead to an argument.

Not talking is going to bring us much closer together.

Another thing that often strikes me in Japan is that if it's a very hot day,

Let's say you,

James,

Are in New York City and it's very hot,

As you go to the post office,

Everyone's going to describe,

Oh,

It's blistering.

You could heat a raccoon.

And they'll all come up with colorful ways to describe the heat.

If I'm walking down my neighborhood in Japan,

Everyone will just say,

That's sweet,

That's sweet.

In exactly the same tone,

Exactly the same cadence,

Using the same words.

And that takes so much of the fiction out of life.

People aren't trying to impress their personality or their individuality upon every passing transaction.

That doesn't matter.

They're actually making themselves,

Again,

Impersonal or invisible to the point where sometimes if I'm walking down the street and I hear a female voice,

I don't know if it's my wife whom I've known for 32 years or a stranger.

Because everybody is deliberately speaking in the same way as everybody else.

And again,

It flies against the norms that many of us grew up with here in the West.

But I think it makes for a very calming as well as harmonious society where all the static of individuality doesn't get into it.

And the texture of public life remains that much more serene.

You know,

When you talk about the de-emphasis of individuality for the sake of harmony,

Or just simply an understanding of how the world actually is,

How dwarfed we are by condition,

I don't know if this is a correct analogy,

But it made me think of the pre-Socratic Greeks.

For instance,

Fate is the prime mover,

Not individual human beings.

I mean,

They become the playthings of the gods.

And so,

And again,

You have this vast backdrop in which all of this action is taking place that seems to be more the central truth or figure than individuals going about their business.

Perfect,

Exactly.

I mean,

As we were driving down for this conversation 45 minutes ago,

I was saying almost exactly that to my wife,

That whether it's Shakespeare's world or Dante's world or Homer's world or all the great cultures that we look to for wisdom,

They all have this sense of capricious gods in the heavens,

The larger presence of time and nature and fate,

As you said,

All of which humbles us.

We don't assume we can remake the world tomorrow,

And we do assume that the world may remake us very,

Very quickly.

And I think there's a real wisdom in that.

And Japan,

I think of Japan as a grownup.

And when I moved to Japan from New York City at the age of 29,

I maybe couldn't have articulated it,

But probably I was thinking,

I want to learn from this wise elder.

It's been around a long time,

Longer than New York City by a factor of seven,

Perhaps,

And it has gathered some wisdom about things.

And I was noticing about ghosts too.

Read the pre-Socratic Greeks or Homer or Shakespeare or Dante.

They're full of ghosts.

They again believe that the lines are very porous between the living and the non-living,

And that death is something,

A presence that we need to keep with us in the midst of our lives.

It's interesting,

When I listen to the Dalai Lama speak,

I often hear the Stoics too.

And I think,

Well,

If these wise presences in Greece and younger wise presences in Tibet have come to the same conclusion,

I should pay attention to the conclusion.

There's probably something going on there.

But I'm so glad you mentioned that,

Because I agree.

I don't think my Japanese neighbors would be at all startled if they were teleported to ancient Greece and were given a sense of what the worldview is.

And they would assume,

Yeah,

This is the way things are.

There are gods governing our lives,

And we just do our best,

But we're powerless beyond a point.

And I think that sense of vulnerability is really useful,

Because it's so easy to imagine we're in control of things.

And now,

Across the planet with cyclones and typhoons and forest fires and floods,

Nature is reminding us otherwise.

You know,

I might get myself into trouble by saying this,

But it seems to me that psychotherapy,

In psychotherapy,

Of course,

There's this hyper focus on the individual.

I mean,

After all,

It's a one-on-one exchange,

And people are talking to each other.

It certainly isn't what we think of when we think of the rather taciturn Japanese.

But it does exist there.

In fact,

Your brother-in-law,

Whom you've never met,

Is a therapist who,

From your perspective,

Is a bit of a fish out of water in Japan,

I think.

But you write,

He might have been bringing the therapeutic way of settling accounts to an old society that thrives by stepping around conflict and allowing the seasons to sort everything out.

And one other quote,

I'm not sure psychology and looking for the human cause of all our suffering can work in a place that flourishes on not looking for answers and ascribing difficulty to something in the heavens.

I thought that was kind of brilliantly put.

Can you talk about that?

I think I understood that correctly.

Yeah.

And I should stress and also absolve you that these are my prejudices that I'm imposing on the situation,

And they're probably wrong.

I'm probably just projecting my own dogmas.

But yes,

So this book begins with my father-in-law suddenly dies at the age of 91.

My mother-in-law,

Aged 86,

That very day has to be moved to a nursing home.

My wife has to tend to all of this.

And her brother,

Who's the only other member of the family who lives 15 minutes away,

Is completely absent.

He disappeared 25 years ago in ways that are more or less unexplained.

And as my wife sends him messages,

You know,

Our dad's in hospital and things are looking bad,

Our mother is declining,

Please come and visit,

No word ever comes back.

Now,

Who knows why that is?

And I've never met my brother-in-law.

But it is striking,

He's the rare Japanese who became a Jungian psychologist.

And he,

Having studied in Kyoto,

Did graduate studies in Kansas and then went to the Jung Institute in Zurich and got his PhD.

So clearly a very intelligent,

Wise man in his way.

But I always think one of my favorite moments from the Buddha is when he says,

When an arrow is sticking out of your flesh,

Don't start arguing about where it comes from,

What kind of arrow it is or who the manufacturer is,

Pull it out.

You know,

That's physician's practicality.

And the question I suppose the book is posing is,

What do we do with suffering?

What do we do when that arrow is sticking in the flesh?

And I think my Japanese neighbor's response is less analytical than it might be in many cultures and is,

You know,

Let's deal with it and let's not look for causes,

Partly because we are human and we don't know and we very likely will get the causes wrong.

But when it comes to pulling out the arrow,

We might have a much clearer sense of what to do.

It's interesting,

This isn't in either of my books on Japan,

But Joseph Campbell famously said,

If you're thinking of going to therapy,

Go to Japan instead and it'll save you a lot of money.

By which he meant,

I think that you used the word economy wonderfully about the expression there,

Verbal expression.

But I think it's a very clean place psychologically,

Maybe because people aren't pushing their agendas,

They're not foisting on you their individual notions.

They're wildly individualistic behind closed doors in terms of their passions and hobbies,

But they feel that the considerate thing to do when they meet somebody else is respond to that person's needs rather than inflicting on them their particular concerns.

And to me,

There are probably flaws in that,

I'm sure,

But there's a healthiness too.

And I went to Japan partly to learn about what a doctor could teach me about not being overly analytical.

I grew up in quite a cerebral intellectual background and I thought,

Well,

I've done my part by that,

But Japan can teach me how to be liberated from overthinking and bringing an analytical mind to something that might be better served by kindness or a practical response.

You mentioned Joseph Campbell in your upcoming book,

A Beginner's Guide to Japan.

When is that coming out?

Is that in fall?

Yes.

So we are mostly talking about this book,

Autumn Light,

Which comes out essentially now.

But I deliberately wrote two books about Japan at the same time that are more or less contradictory.

And my idea was to bring them out at the same time and my publishers wiser than I said,

Let's put a few months between them.

So this book called A Beginner's Guide to Japan comes out in September and I think you've already looked at some parts of it.

And my thought was whatever we're describing or assessing,

Whether it's our hometowns,

Our mothers,

Our adopted homes,

We see them through many lenses all at once.

And so the book,

Autumn Light,

Is really meant to be about to pitch the reader right into the thick of daily life in a typical neighborhood in Japan to the point where she's not really thinking about Japan,

But she's thinking about parents and children and absent brothers and universal stuff.

And it's really meant to be about approaching Japan through the heart and through sympathy and what does it feel like to be in Japan.

The second book that comes out in September is full of an outsider's wild prejudices.

And there my persona is that of a westerner who's just arrived off the plane and is trying to explain everything from the baseball games to the wild fashions to the temples and the gardens and the history of Japan.

So it's lots of provocations,

But it's very much an analytical book and a western take on Japan where my hope is that in the Autumn Light book one loses all sense of distinction between west and east because one's rooted in the human.

And I must say that one of the things I most appreciate about Japan is it does for me,

Free me from binaries.

I think growing up in the west I was tempted a lot to think in terms of you or me,

This or that,

All those kind of things.

And while Japan does have that in certain ways,

I think it knows that life and the universe are subtler than black and whites and that,

As Graham Greene said,

It's mostly about operating within a thousand shades of gray.

And with the dead,

For example,

You could say they're not present,

But that doesn't mean they're absent,

That they live in some middle space between those two extremes.

And so I suppose the Autumn Light book is a little bit about living in that middle space because autumn is on the one hand the culmination of summer and it's also on the other the first step towards winter and also,

As I was saying,

Every day in autumn is bringing you closer to spring.

So you can't really take refuge in hard and fast distinctions.

And those are some of the things I wanted to learn from Japan.

Well,

Both books go so well together.

Right now,

Autumn Light is available and we're very much looking forward to September then.

I don't know if I sent you the quote,

The Joseph Campbell quote.

I don't think I got it.

I'd love to hear it.

Okay,

Because I just wanted to ask you about it because I thought it was so astute because the way we understand Zen in this country is in so many ways conditioned by our Western culture and it's often vastly different in Japan.

So you write,

For a Westerner,

Joseph Campbell noted in Japan,

Meditation may awaken a sense of divinity within.

For Japanese,

It's more likely to inspire a sense of divinity inside a temple,

A flower,

A gnat.

The person sitting still doesn't say,

I'm awake.

She says,

The world is illuminated.

That seems to me to capture a real psychological split between East and West,

If it's fair to even say that.

But what do you mean by that?

I guess I mean that the nature of self,

The nature of community,

The nature of surrender,

I think are all very different between East and West.

And I suppose that's an interesting issue for a magazine about Western Buddhism to address.

I think I also say in that book how in my experience within the Zen temples of Japan,

And I haven't done a Zen practice,

But I've been around temples a lot,

The Japanese teachers are very excited when Westerners come because they're much more motivated.

They're coming because they want to study Zen.

The Japanese students are often there because they've inherited a family temple and they have to be there whether they like it or not.

So I think the Western students bring much more excitement,

Engagement,

Real sense of inquiry to the practice,

But for the same reason that restlessness often takes the Westerners away from Zen practice after at least away from the temple,

Whereas the Japanese guys who are doing it for reasons of duty and responsibility will stay the course.

And so as somebody who's partly Eastern and partly Western and has really spent my writing life for 32 years looking at the way the two of them dance around one another,

I've always been fascinated by,

Again,

My subjective sense of how that same tradition which has taken on new identities in Tibet and Thailand and Japan and everywhere it visits is now acquiring a whole new identity.

And this is the subject of tricycle wonderfully in the West.

And I should say because this is a tricycle conversation that one of the elements I really wanted to stress in the Autumn Light book is there's a whole section about the Dalai Lama coming to Japan,

Visiting the area that was stricken by the tsunami and dealing in this practical physician's way with the suffering of people who had lost everything in the world.

And part of the book is also about the Zen master in whose temple I met my now wife.

And it was interesting that when my wife divorced her first husband and then took up with me,

Most people around her in Japan were frowning and giving her a hard time practically,

Socially,

Emotionally.

But the Zen master was completely free of that,

Generously said he would give her all the support,

Practical and moral that she needed and was a fountain of open-minded compassion I would say.

He was not bound by the rules of Japanese society but saw some deeper truth.

And he always used to say that one of his favorite symbols in the world was a bridge.

And he had made it his practice,

Although he'd seen his country devastated by American bombs,

To make a bridge between the Japanese Zen tradition and the West.

So he would visit this country every year and talk for 30 days across the nation.

And so when I met my wife in his temple,

He would say,

I'm your cupid.

He was delighted that we'd met under his auspices.

And I think that was another kind of bridge for him.

And just the way that Buddhism,

Whether in that instance or through the Dalai Lama,

Is about breaking through,

Dissolving barriers,

Breaking through divisions.

And that's one of the most inspiring aspects of that tradition for me,

Whether in the East or the West,

The fact that the Dalai Lama gives talks on the Gospels and calls himself a defender of Islam and publishes a book called Beyond Religion.

I think that's what the global world needs more than ever.

And that's one of the great things that Buddhism can contribute to everybody,

Whether you're a Buddhist or not.

Just the wide view to see things beyond binaries and to realize that we have more in common than apart.

And that when I leave this conversation,

If I walk into somebody from Afghanistan of Islamic faith,

It's not so difficult for me to find what links us.

We have kids,

We have wives,

We worry about the economy rather than the small things that separate us.

Well,

That's so beautifully put.

You know,

You mentioned Western Buddhism and certainly when we began,

We thought in that way too.

But I think in your book and you as an example is pretty much describes what we're experiencing now at Tricycle say,

We're discovering this notion of Western Buddhism is getting ever shakier.

In other words,

There's so much contact between cultures and urban centers now that the line is becoming ever more blurred.

And I think that's a really good thing.

For instance,

Our inclusion in over the past 10 or 15 years of Pure Land Buddhism was something that many Western convert Buddhists had never really considered before.

So all of those barriers,

I sense are coming down to whether it's,

You know,

We refer to Western Buddhism,

But that is becoming less distinct,

I think,

Rather than more so.

Do you have any sense of that?

No,

That's wonderful.

And you know much,

Much more about this than I do.

But I love the fact that Buddhism in Europe and North America is becoming as diverse as it is in Asia.

And as you say,

The same core principles,

Whether you're in Laos or Germany,

But each culture can refresh it and remake it in the light of its own,

Not just each culture,

Each community.

So it's a wonderful thing if even the notion Western Buddhism or that term disappears,

Which is probably a large part of what you are doing in Tricycle.

And it just becomes one new iteration in this wonderfully evolving tradition of 2,

500 years.

You know,

We may end on your last statement because it was so beautifully put,

But I just have one more question since we're running out of time.

I was so taken with this idea,

Just sort of the fluidity of identity in Japan.

You say they're at home and they're one person,

They go out in the world,

They're another person.

But in fact,

They slip in and out of roles so easily and seamlessly.

And for us,

We think,

Well,

That's hypocritical.

You've got to be constant.

And in Japan,

There seems to be this sort of celebration of just changing hats or changing clothes or changing identities,

Depending on,

Again,

The backdrop.

Do you want to say something about that?

So well said.

I mean,

Famously at a Japanese wedding,

The bride will wear probably three different costumes.

She'll wear traditional white Shinto hood.

Then she'll wear probably a classic Western wedding dress.

And then she'll wear chic black Chanel dress for the reception or something cool or something more cutting edge.

In the last week of the year,

The Japanese think nothing of going into a Christian church to hear Beethoven's Ode to Joy on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day.

On New Year's Eve,

They'll go to a Buddhist temple to hear the bell rung 108 times to purge the sins of the year just passing.

And at dawn on January 1st,

They'll go into a Shinto shrine to set an auspicious tone.

So exactly so.

They don't see a contradiction.

And again,

I think it's we who are caught in this rather simple black and white notion.

Because the fact of the matter is that at the end of this conversation,

If I describe it to my mother this evening,

I'll describe it in a very different way than I do to my wife.

And both of those will be very,

Very different from the way I describe it to my best friend and very different from the way I describe it to a passing acquaintance.

In other words,

We too have these myriad selves and we respond to every event in different ways.

And when we're emailing or texting our friends or talking to them,

We'll describe the same event in six different ways.

Our father's death in six different ways to six different people,

Depending on our relation to the people,

Who the people are and the context.

And yet we reside in this illusion of a single self.

And I think the Japanese are happy to say,

No,

We all have many selves and let's acknowledge that.

And by acknowledging it,

Work with reality better.

So it's no hypocrisy for me at the end of this day to say I had a wonderful conversation with James to my mother and to say to another friend,

Well,

We talked about this and this and this and this.

No contradiction there.

And I think the Japanese are much more interested in the notion of cohabitation than contradiction.

The same way that when you go to many a Japanese meal,

You will have the dessert,

The first course and the main course all in the same tray as in an airline.

So it's not as if the dessert is contradicting the first course,

But each serves its place and we can enjoy all of them.

So Pico Ayer,

It's been fantastic talking with you.

I hope we get a chance to talk again soon perhaps when I'm out in Los Angeles,

I can drive up to Santa Barbara.

Please,

I'd love that.

And I'd love for our readers to pick up a copy of Autumn Light.

It's a truly beautiful book.

It's a lyrical ode to autumn,

I would say,

And to Japan.

And thank you very much for taking the time to speak with us.

I really,

Really enjoyed it,

James.

And thank you for taking such time and care with your questions and reading the book.

That's quite a luxury for writers.

I appreciate it.

Okay.

Well,

Congratulations to you.

It's a wonderful,

Wonderful piece of work.

Thank you so much.

You've been listening to Pico Ayer discuss his two most recent books,

Autumn Light and a Beginner's Guide to Japan on Tricycle Talks.

Tricycle Talks is produced by Paul Ruist at Argo Studios in New York City.

I'm James Shaheen,

Editor and publisher of Tricycle the Buddhist Review.

Thank you for listening.

4.8 (101)

Recent Reviews

YC

July 21, 2024

Beautiful conversation and insights about Japan, ritual, human connections, and home away from home.

Luisa

November 25, 2020

Pico has a beautiful mind. I feel grateful for getting a peak in to his mind and just listening to him describe and explain things. Thank you Tricycle for always having thought provoking and brilliant guests. ✨

Karen

July 12, 2020

Love to think what the world could be like if we all prioritized harmony. Thank you. ❤

Ellen

June 28, 2020

I really enjoyed this talk! I have never been to Japan but have always been fascinated with the culture. Very insightful conversation.

Angela

June 25, 2020

So beautiful and inspirational. As someone who lived in Japan for many years and returns annually, this talk and Pico’s wonderful books speaks so much to my own deep love of Japan and many of my own insights and experiences. Domo Arigato

Xanadu

June 16, 2020

Lovely talk! enjoyed the insight shared. Thank you