48:43

48:43

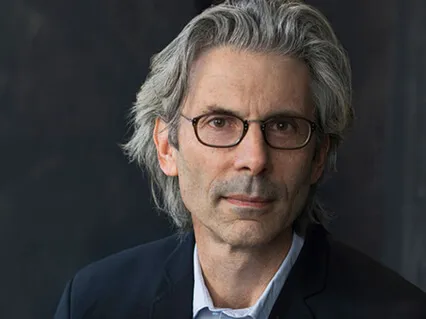

Mark Epstein: The Task Is Being You

by Tricycle

Rated

4.8

Type

talks

Activity

Meditation

Suitable for

Everyone

Plays

20.8k

The Buddha had a prescription to end suffering—the eightfold path. But can the Western tradition of psychotherapy build upon these essential steps? Here, Buddhist psychotherapist and bestselling author Epstein talks with Tricycle contributing editor Amy Gross about how the two realms of wisdom view the idea of self as both problematic and helpful. Drawing from his new book, Advice Not Given: A Guide to Getting Over Yourself, to discuss the ways meditation illuminates aspects of ourselves that we’re afraid or ashamed of, allowing us to let go of the identities that constrict us.

BuddhismPsychotherapyEgoEightfold PathMeditationParentingImpermanenceRight ViewCompassionRight SpeechSelf EsteemDeathDyingBuddhism And PsychotherapySelf Esteem BuildingDeath And DyingParent Child Meditations