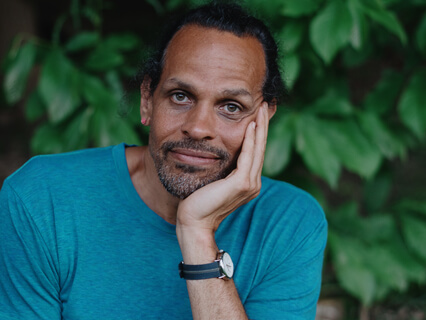

Joy As A Practice Of Resistance And Belonging With Ross Gay

by Tricycle

In this episode of Life As It Is, Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, and co-host Sharon Salzberg sit down with poet Ross Gay to talk about finding joy in the midst of grief and sorrow, the dangers of believing ourselves to be self-sufficient, and how joy can dissolve the boundaries between us. In his new essay collection, Inciting Joy, Gay explores the rituals and habits that make joy more available to us, as well as the ways that joy can contribute to a deeper sense of care.

Transcript

Hello and welcome to Life as it is.

I'm James Shaheen,

Editor-in-chief of Trisicle the Buddhist Review.

It can be so easy to dismiss joy as frivolous or not serious,

Especially in times of crisis or despair.

But for poet Ross Gay,

Joy can be a radical and necessary act of resistance and belonging.

In his new essay collection,

Inciting Joy,

Gay explores the rituals and habits that make joy more available to us,

As well as the ways that joy can contribute to a deeper sense of solidarity and care.

In today's episode of Life as it is,

My co-host Sharon Salzberg and I sit down with Ross to talk about finding joy in the midst of grief and sorrow,

The dangers of believing ourselves to be self-sufficient,

And how joy can dissolve the boundaries between us.

So I'm here with writer Ross Gay and my co-host Sharon Salzberg.

Hi Ross,

Hi Sharon,

It's good to be with you both.

Good to see you.

Thanks for having me.

It's good to be here.

Thanks for coming.

So Ross,

We're here to talk about your new book,

Inciting Joy,

Which builds on your earlier essay collection,

The Book of Delights,

Which I also very much enjoyed.

So to start,

How did you first come to write about joy and delight?

You know,

I have a book before The Book of Delights that's called Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude,

And maybe that was the first time that I was very conscientiously writing about gratitude.

But it wasn't until having conversations about that book,

Which to me has a complicated idea of gratitude.

It's built of odes and elegies.

That's what that book seems to me to be about.

But having conversations about that book,

People were talking about joy,

And it made me start to consider more deeply this idea of joy.

It's interesting because a lot of people when they hear the words joy,

Gratitude,

Delight,

They just groan.

We live in such an age,

I guess.

But you mentioned a student who said they'd always been told they couldn't write about joy because it wasn't serious enough.

How do you understand a comment like that?

I make a joke about a dishwashing soap called joy.

Yeah,

I remember.

Like it's a kind of lightweight,

Maybe you'd say consumerist,

But definitely not a serious emotion.

And that's not it at all.

Joy emerges from the understanding that we live in the midst of profound difficulty,

Not only,

But in part.

Joy seems to me to be the practices of entanglement.

When we're sort of entering the practices of understanding that we belong to one another,

We are not separable from one another,

What comes from doing those practices is joy.

Which is why you can weep with joy,

You know.

Weep sadly with joy.

I was looking online and watching you read several of your poems.

And you do read them sometimes with great joy,

Despite an underlying sense that there's also pain there.

And instead of imagining joy as separate from pain,

You suggest that it emerges from how we care for each other through sorrow and suffering.

I was especially moved by your description of the end of your father's life.

And yet joy still surfaces.

Can you say more about how you came to this understanding of joy?

It's beautiful to be talking to you all because I feel like a lot of it comes from contending with a mind that was often troubled.

I spent a good bit of time realizing that I was trying to resist.

I was trying to fight back something.

I spent a lot of time fighting to avoid my sorrow.

I spent a lot of time struggling on account of trying to hold back,

Push away sorrow or isolate myself from my sorrow,

Which is also,

I think,

A way of isolating myself from other people.

One of the teachings,

It feels like a life-changing teaching,

Was actually in a mindfulness class at Thomas Jefferson Hospital in Philadelphia.

We were just doing like a body scan meditation.

And the teacher asked,

How did it feel?

And one of the students in the class said she didn't like it.

The teacher said,

Well,

Why not?

Are you okay to talk about it in that very good teacherly way?

This is all new to me.

And she said,

What made me sad?

I can't remember exactly what she was talking about,

Maybe something to do with her son or something like that.

As that was going on,

This class of about 30 people,

They were across the circle from me.

I realized that I literally couldn't watch.

I literally couldn't look at them.

It was not like someone having a finger cut off.

It was like someone saying they're sad.

I'm sad.

But I couldn't bear to look at it.

I don't know that I would have noticed it without the lessons from that class,

Actually.

But the thing that I noticed was that in my body,

I was having the same exact feeling that I would have when I would go to visit my mother.

My father had died.

My mother's partner of 35 years had died sort of recently.

And she was really sad.

And it was so difficult to be with her in the midst of that sadness.

And I learned to watch my mind with ways I would try to get out of being with that sadness.

And being with that sadness to me is sort of like,

Well,

That's called joy.

Being with your mother in the midst of her sadness is one of the aspects of joy,

I think.

I think it's really powerful what you're saying,

Actually,

Because we can have so many conditioned reactions to a sense of sorrow,

Which is not allowed for many people.

We might do just what you described so well,

Avoiding it,

Denying it,

Trying to pretend it's not there,

Or the other extreme,

Being overcome by it and defined by it,

Not having a bigger perspective.

And you're talking about this middle place,

Which is so incredible.

And you use an image of inviting sorrow in for tea,

Which exemplifies that middle place.

And it reminded me,

Of course,

Of the story of the Buddha inviting the kind of a satanic figure in Buddhism,

Mara,

To tea.

But the tea soon turns into a neighborhood potluck full of dancing and raucous celebration.

And I wonder if you could say a little bit more about that image of the neighborhood potluck and the boisterousness that can come from sharing our sorrow.

I'm glad you brought that up,

Because I think there's a way that we can become overcome by sorrow.

One of my guesses or hunches is that if we don't reject our sorrow,

We don't reject the sorrow of other people.

And if we know that sorrow is not unique to us,

Maybe we are less inclined to be overcome by sorrow.

Again,

I think that potluck itself,

A kind of practice of entanglement,

And all of the things that happen in that potluck,

Where there's a group of people who start to have like a fermentation group,

And then a little coven forms of people like dancing and all this,

Making kites out of the obituary pages.

It feels to me that all of these practices emerge not only because they're there with their sorrows,

But actually in a way to acquaint themselves with and be able to be with their sorrows.

And so when the sorrows get invited in,

It's actually a party where people figure out how to care for each other.

That was a great way to start that book,

Inviting everyone's sorrows in.

Like Sharon,

I really love that.

You organized the book around two guiding principles,

Investigating the rituals and habits that make joy available to us,

And exploring how joy makes us act and feel.

In other words,

What incites joy and what joy incites is the way you put it.

Can you say more about these principles and how they've shaped how you see joy as a practice?

The question that I ask,

What occasions or what incites joy?

It's sort of,

In a way,

Back to that question about the student saying,

Well,

I've been told that joy is not serious.

Why should I be thinking hard about joy?

And to me,

What I've found to be true is that what incites joy in fact is deadly serious,

Including the fact that we die,

The kind of mutual understanding that things change dramatically.

We grieve,

We suffer,

Et cetera.

But as far as the other guiding question of what incites joy,

As I was getting closer to understanding how to talk about it,

Like these practices of entanglement,

What are the things that we actually do in our lives that practice what makes joy?

What are the things that we do in our lives that we might not even articulate as joy inciting practices,

Experiences,

Et cetera?

For instance,

I talk about pickup basketball.

I talk about gardening.

I talk about dancing.

But I think a lot of these things that I'm talking about are ways that we practice making room for and accommodating as many of us as possible.

The other thing is that there are often these practices where the divisions between us get murky,

Like dancing hard.

The idea of you and me changes when you're dancing.

Anytime you're growing a garden,

What I think of as a very regular practice,

Not a special practice of the garden,

Is to share.

You got extra zucchini,

You share them.

Your potato harvest was wild,

You share the potatoes.

That troubles the idea of you and me,

That sharing itself.

Obviously,

It's a practice of joy,

But it's also like a troubling of this boundary between you and me.

Daishi,

What incites joy and what joy incites,

I can see how that becomes blurred in the way you've just described this.

I'm going to quote you.

You say,

Joy can kindle wild and unpredictable and transgressive and unboundaried solidarity,

Which in turn can incite further joy.

Can you tell us about this transgressive power of joy in bringing us together across boundaries?

It's my understanding and my sense that there's extreme care,

Say like a pickup basketball court.

There are these radical acts of care actually that will happen on basketball courts numerous times during a game.

Or if you think of organizing a strike or something,

People who might really disagree about stuff,

Really gathering.

What does it mean when people who think,

Who've been told they're not supposed to care about each other,

Really love something together,

Really come together around something,

Whether it's a song,

Whether it's a garden plot,

A waterway,

A road that we don't want to go through.

It feels to me like it's dangerous,

That transgressive joy,

That transgressive gathering.

I'd like to go back to gardening for a minute because it's very,

Very different from me.

I don't think I've ever kept even like a house plant alive.

So I felt like I got some glimmer of an insight listening to you.

And so I want to go further into it because when you talked about sharing,

I thought about how it opens us to insight into so many conditions and giving and receiving.

Like maybe somebody had a very poor harvest,

But it's not their fault.

It's not like they're a bad person or a bad gardener.

It's the soil or the rain or something like that.

It can really reveal a lot about the nature of connection and also giving and receiving.

So I'm curious how you first got interested in gardening.

Oh,

Good question.

I moved to Bloomington like 17 years ago and I had lived mainly in Philadelphia or Jersey City or places where I hadn't gardened.

My mother grew a couple flowers in front of the apartment where I grew up.

But her folks were farmers and by the time we were five or six years old,

They had moved into town and they kept serious gardens.

And then people on my dad's side of the family also garden sort of seriously.

I often used to talk about,

I first started gardening when I moved to Bloomington.

But the fact of the matter is we grew up where there's wild raspberries along I-95 and there was a mulberry tree.

So there was a kind of relationship with fruit particularly.

But when I did move to Bloomington,

This is a town where people really garden.

My partner is a gardener.

That was an influence.

I had someone in the first class that I was teaching here who is a really serious gardener who was just talking about it so enthused.

Another buddy who became a buddy from that class was a serious gardener.

And one time I was riding around town in Bloomington and I saw a guy at a community garden turning mulch.

I asked him what he was doing and he said,

We're turning the compost.

And he asked me to join him and I joined him.

And then I got involved with this community orchard project here in Bloomington.

And that's a real central part of my life now.

Just on my way here,

I was walking and bumped into this guy who's a farmer in town and we just had a conversation about garlic because he sells garlic and it keeps real good.

And I was asking him for advice.

We had this exchange,

This sharing actually on the sidewalk.

But in a deep way,

It was here that it started.

You refer to gardens as archives of love,

Records of the people who've cared for us by saving and planting seeds.

I wonder if you could say just a little bit more about that and interdependence.

We are in a tech world where we imagine we can invent ourselves out of everything.

But the fact of the matter is that so much of what we grow has been brought forward.

People had to select the seeds.

Seeds are selected.

Seeds are kept.

Plants go to seed and people will keep those seeds if they love the plant.

And they might love the plant because it tastes good or it's beautiful or it grows in certain conditions that are difficult or their parents kept it and their parents and their parents.

Anytime you're growing a garden,

You're growing the kind of archive of love.

And you may not know the whole story of the love.

Of course you don't.

But you know that it's the evidence of love.

That's the evidence of care.

Multi,

Multi,

Multi-transgenerational care,

Epigenetic care.

You don't outsmart the earth.

You are always the recipient of the kindness of the earth.

When you grow a good crop,

It's not because you did it.

It's because not only the seeds,

Not only the soil,

Not only the rain,

Not only the light,

Not only the wind was okay,

Not only the birds didn't eat it,

Not only the chipmunks,

All of this stuff has to happen,

This interdependence in order for it to come.

You could just as easily have a terrible crop of collard greens as you could have a great crop of collard greens.

When we can kind of get our heads around that,

Our hearts around that,

It feels like,

Oh yeah,

We all need.

We're all in a perpetual state of need.

We need the light to be right.

We need all of this.

We're constantly the beneficiary of this kind of generosity.

Daishi So talking about interdependence and what you learn from gardening,

I have to ask about the dangers of believing ourselves to be self-sufficient,

Especially when it comes to our relationship to the earth.

And you say that,

Quote,

When we refuse to celebrate the earth's kindness,

We prepare the ground for the earth to refuse kindness to us.

So what does it look like to accept and celebrate the earth's kindness?

That makes me think of when you first started thinking about your own sorrow,

Your inability to share that with others.

Daishi A useful practice is to notice how much of the earth explicitly makes one's life worth living or maybe livable,

Period.

You could walk out the door and you wouldn't get down the block.

Like to talk about the trees,

That is not only about what they offer to the creatures and that they make shade and that they take care of the air.

There's a million things that we don't know.

It's beyond.

A useful practice is to acknowledge again and again and again how much we're indebted to the earth.

Maybe you note it.

Oh yeah,

If it wasn't for that.

One of the sorrows of a certain kind of masculinity is to reside in this dream where you think that everything you do is on account of yourself.

We might in fact commit incredible harm.

We might be incredibly brutal to keep that illusion up.

Instead of acknowledging that my water comes from a place,

To avoid acknowledging that,

I could do anything.

I could be incredibly brutal.

Or the complete isolation we inflict on ourselves when we do that.

Yeah.

It's impossible to live that way.

Totally,

Yeah.

It's a brutality to oneself too.

What a lonely life not to be paying attention to the kindness that is offered.

What a sad echo.

What a lonely life.

In a later chapter in the book,

You catalog your work developing a community orchard.

You write that planting the orchard revealed a matrix of connection,

Of care,

That exists not only in the here and now,

But comes to us from the past and extends forward into the future.

Can you say more about this network of care?

I remember I had a former colleague here at IU and he talked about how people would plant black walnut trees and they would take 25 years to grow big enough.

They plant them for their grandkids maybe.

It would take long enough that they'd get big and you could harvest them for board wood and pay for someone's college.

It was such a kind of beautiful idea of tending to something for the future.

Planting trees is so often that.

This community orchard,

Just to talk a little bit about that project,

My friend Amy Countryman had this idea of a community orchard.

She had this phrase,

Free fruit for all.

And we all got behind that.

The idea was like,

What if we grow an orchard?

It's going to be open and you can harvest what you want.

We were a bunch of people who for the most part didn't know each other.

I didn't know any of these other people who I was working very hard on this project with.

But the thing that was so moving to me about it,

And it got more and more moving as I realized as it became clear to me,

Is that fruit trees take a while before they get into full production.

I teach college.

One of the things that college teachers do is they move around a lot.

It wouldn't at all be unusual if I were to be gone by the time.

But also trees take 10 years to get into full production.

People die in 10 years.

And it felt like we were people who were coming to know each other and we were gathering around this idea of these people in the future who we didn't know who might be able to harvest fruit.

That was the reason that we gathered.

We liked the idea that in the future,

There'll be fruit here for people.

And doing that project also made me aware of how often that has happened for me.

Again,

To talk about the seeds,

People selecting seeds,

Saving seeds,

Carrying seeds.

That is the evidence,

One of the zillions of evidences of people behaving that way for my benefit.

It was just so beautiful and moving to me because I don't know that I had had the occasion to think as hard and clearly about that as a kind of practice,

A kind of practice of thinking about,

Oh,

We're going to make this thing that's going to care for people that we don't know and can't imagine.

And the care is going to be really unabstracted care.

It's going to be like pears.

Daishi B.

Meyer You know,

I guess growing trees takes a lot of patience.

I grew up around a lot of fruit trees.

I know how long they take.

And you talk about our relationship to time,

Especially through activities that run counter to our entrenched notions of productive time or capitalistic time.

And this seems to be a running theme for you as you devoted a chapter in the book of Delights to the Joys of Loitering,

Which I remember well.

There was great humor there in taking one's time.

Can you say more about how society has conditioned our understanding of time?

And can we break out of this model of scarcity and instead view time as abundant?

Dr.

Michael Kahn I think it's tricky.

I think there's all kinds of ways.

I've been thinking hard about how my mother,

She's 82 now,

And she worked 10 hours a day at a job she didn't care about.

And then she had a paper route on top of that.

And then she had the hustle of the broke.

My dad too,

But I'm thinking about my mom because my mom's still alive.

And there was a scarcity of time for her.

She didn't have a lot of time to kick back,

In fact.

And now she has a lot of time to kick back.

She's retired.

When my dad died,

He had good life insurance.

And so now her concerns are very different.

What does it mean that I have a kind of abundance of time?

And that there are so many,

Many,

Many,

Many,

Most people,

I would say,

Who due to various straight economic conditions have a scarcity of time imposed upon so many of us.

So that's one thing that I would say at first that I sort of think about.

And I think about,

You know,

My mother,

Where I'm like,

Gosh,

She's so delighted.

Oh,

That's right,

Because he's not looking at her watch.

And she's not terrified about her bank account.

The other thing is that I also think there's a kind of compulsion period among so many people to be productive,

To be acquisitive,

Always on the go.

That essay definitely made me think or wonder about joy.

And also,

I think in that essay,

I might say mongrel gathering,

The kind of,

Again,

Transgressive gathering.

And also knowing what feels important to us in our lives.

It seems like it often happens outside of a temporal compulsion.

It happens often when we're doing nothing.

Sometimes that's when a kind of clarity of purpose or desire or curiosity can arrive.

It's interesting,

Though,

Because when time is abundant or when people do have time,

Sometimes they speak of killing time.

I wonder,

Is that term a kind of relationship to what you're supposed to be doing with your time?

You know,

Kill the time until it's time that you're making money.

Or it's sort of turning away from that space that opens up,

The way you might turn away from sorrow,

Say,

Or the way you may lack the imagination to sit with that time and let something come up.

I've experienced it myself.

I think most of us have.

But you cite Auden's famous line that poetry makes nothing happen.

Yet rather than reading this as a dismissal of poetry,

You see it as a celebration of poetry's ability to make nothing happen,

To stop time.

You say more about the nothing that poetry makes happen and maybe a little bit about what I refer to when we sometimes have the compulsion to kill time.

One of the things that's interesting to me about poems is they slow you down.

And they require often a kind of contemplative relationship to something.

The way I think of poems is that they are extremely bodily.

A line of a poem,

To me,

Is a breath.

So a poem is made up of breaths.

A poem is a kind of body.

And there's some way that being in residence with this breathing thing,

There's some kind of absence of getting-it-doneness with a poem.

But maybe it's a getting-withness or something with a poem.

Yeah,

I've loved that line for a long time because people really tussle with that line and they want to argue with it.

And I'm like,

Well,

I don't know if it means that thing that you're talking about.

If we're making poems,

We're not making bombs.

I'd like to just suggest that anybody listening who would like to see Ross read his poems,

Go online and look him up.

It's a real joy to watch you recite those poems.

Let's take a quick break and we'll be right back.

Are you curious about books and authors who have influenced civilizations for millennia?

Love conversation that connects rather than divides?

Continuing the Conversation is a web and podcast series that examines the mysteries of who we are as humans.

Using 3,

000 years of great books as a guide,

The series is produced by St.

John's College,

A secular liberal arts college known for great books and great dialogue,

Offering a bachelor's degree in liberal arts and master's degrees in liberal arts and Eastern classics.

Listen to Continuing the Conversation on podcast platforms and the St.

John's College website,

Sjc.

Edu.

That's sjc.

Edu.

Now let's get back to our conversation with Ross Gay.

You also describe how you incorporate practice of joy into your pedagogy,

Particularly as a means of countering some of the strictures and stresses of traditional academia.

So how do you invite creativity and joyful exploration into the classroom?

If it's anything like you're reading your poems,

I want to take a class.

Well one thing is that I try to do as much collaborative stuff as possible.

And I talk about this in the essay.

So often the classroom is a place where you want to distinguish yourself.

Because I am thinking about joy,

Et cetera,

As not necessarily a kind of isolated experience,

But an experience of gathering and joining,

I want to make the classroom a place where we can actually do that.

That's one thing,

As much collaboration as possible.

And then as much experimentation or play as possible.

This relates a little bit to the time question I feel like.

Usually students who are in college or students who are in grad school are pretty good at being students.

They know how to follow directions and be like good enough.

And in a way I'm sort of like,

Well,

What if we just threw that out?

And what if instead our project was not to be good,

But our project was sort of to get lost and to sort of wander around together?

That's another thing that I try to do in my classes.

And another thing that I do in my classes that maybe permits this kind of being lost and encourages us not to want to distinguish ourselves,

Isolate ourselves in a way,

Be solely excellent.

I don't grade,

Or I give everyone A's in my classes.

So I just start off with the idea that we're just not doing that.

That's not the objective of this class.

The objective of this class is care and it's metaphor.

Let's work on our care and let's try to make good metaphors or something.

I want to go to this class too.

You'd get an A for sure.

I had a moment thinking,

God,

Where were you when I was in college?

I think a lot of people did.

Well another incitement is laughter.

And you write that your friend once said to you that when you laugh,

You look like you're dying.

So can you say some more about the relationship between laughter and dying?

It's funny.

I was taking a walk with that friend,

Dave's name is.

He's very funny.

He makes me laugh really hard.

And that I'll kind of gasp and he was imitating it this weekend in a way that was really cracking me up.

But you know,

Like one of the things when we laugh,

We gasp,

We breathe,

We become acutely aware maybe of the fact that we're breathing.

Laughter is so often the evidence of our being connected to one another.

We make each other laugh or we laugh together at similar things.

But again,

Because the breath part of it is so important.

Like that gasping is actually a part of breath,

A part of laughter.

It feels really connected to the fact that we are in the process of expiring in a certain kind of way.

And to come to the idea of like killing,

Comedians kill.

When they make everyone laugh really hard.

But yeah,

I'm glad you mentioned that essay.

You have a wonderful line when you wrote,

Laughter draws us together by reminding us of the dying we share.

Yeah,

It feels like another one of the ways that we tend to one another is passing.

You talked about caring for your father in the last months of his life.

And earlier you told us that you had difficulty holding sorrow.

And here you say that you were terrified of grief.

Why were you afraid?

Maybe that's a rhetorical question,

But still it would be interesting to hear the answer.

And what do you think was so destabilizing about the prospect of grieving?

I think one of the things that grieving does is that it makes it very plain that you are connected and you are not this isolated singular entity,

But that you are fundamentally permeable.

And maybe more than that,

You're fundamentally everything else.

And I think that is terrifying.

And I think maybe it's more terrifying based on your conditioning.

Sometimes I think of growing up as a man or growing up in these certain kinds of ways where being moved is not particularly permissible or being needy or being made of fundamentally other people is not permissible.

And grief,

Being heartbroken,

Devastated by heartbreak,

Maybe it's the evidence of that.

I think that's a thing that I'm sort of regularly contending with,

The fact that sometimes I want to protect myself from connection,

Even though my sort of whatever,

Higher self or a truer self who understands that you don't protect yourself from connection.

And to protect yourself from connection is really to be sad,

Like we said.

It's really lonely.

Grief is the evidence of fundamental connection,

And that can be horrifying.

What do you all think about grief?

I tell you,

For a good part of my life,

Did not know how to be alone and I did not know how to be with other people.

And learning to do one helped me with the other.

But grief is one of those things that you either break or you open to others.

For me,

That's just pretty much how it was.

And I like the way you say it.

It bespeaks connection.

It almost imposes connection on one.

But if you're open to it,

It's the only thing that really saves you that others are grieving with you.

Somebody once said something that I think about a lot,

Which is grief is love that doesn't have the normal place to land.

The person is gone or the situation is gone or the hope that things would work out a certain way is gone.

But it was the love that drove it in a way.

If we didn't have the love,

We wouldn't be as distraught at the loss.

It's almost like grief is a vehicle for joy.

Not joy that we're happy something has happened,

But in finding one another,

As you've been saying.

You've written that you've come to see grief as the metabolizing of change.

I was intrigued by this definition because I've sometimes used that term talking about one of my own meditation teachers,

This woman named Deepama who began her life as a meditator having suffered terrible,

Terrible loss and trying to describe what happened to her in her first meditation retreat.

She somehow metabolized all that pain and it became compassion.

Yeah,

It's beautiful.

The connection and the love doesn't go away.

And I think that could probably be the devastation.

When we talk about being consumed by grief,

I wonder if that is sort of like,

Oh,

Well,

The love is gone or the connection is gone.

But I think the love isn't gone.

And I think there is this question of how we relate to the changing of the love that we can no longer walk with the person or we can no longer call them on the phone.

Metabolize is kind of interesting.

I love that it's profoundly bodily.

This is in our bodies.

There's a certain amount of grief you feel that is the residue of love.

And that's a beautiful thing and that can give rise to joy.

There's also a kind of grief that comes from a sort of attachment that feels more difficult and less joyful,

An inability to let go.

Those both seem to coexist within the grief and grief that is a residue of love is what I think you're talking about.

Yeah,

That's right.

So you also write about grief as a form of atonement,

A way to recognize and mark the harm we've inflicted.

Can you say more about how we can grieve the subtle harms and daily hurts that we cause?

Yeah,

I started thinking about that in earnest when I was in couples therapy or something.

It seems like the condition of being a human being is to be actually hurting other creatures,

Maybe the people closest to you in a certain kind of way.

Learning about couples therapy stuff not only in this relationship either,

Not only in my primary relationship,

But in all kinds of friendships and everything else,

With my mother,

Like all these other relationships,

I've noticed this.

There are instances where I've done something that I might like to apologize for.

I've hurt someone in some kind of way.

And I'm not talking big drama or anything,

But maybe.

And there's a part of me that wants to refuse that,

To refuse the acknowledgement of that.

And then the refusal of the acknowledgement encourages me to do something else that I would rather not do,

As opposed to just saying,

Hey,

I think maybe I hurt you and I'm sorry about that.

It's so much harder to do,

But so much easier in the end.

Oh my God,

I know,

It's wild,

It's wild.

And you don't always hear back what you want to hear.

And that has to be okay too.

I know,

I know.

So we recently had the novelist Ben Okri on the podcast.

I don't know if you know Ben Okri,

But he spoke about how when we refuse to face difficult truths about our country's past,

Those truths grow and continue to cause harm.

And you describe a similar dynamic on an interpersonal level.

When we avoid acknowledging that we've caused harm,

We end up continuing to hurt ourselves and the people around us,

More or less what you were just saying.

So I guess breaking the cycle of hurt then would be to acknowledge the hurt we've caused.

Is that right?

Oh,

I think so.

And I think on a kind of national level,

That's just so obvious in that essay.

I make a kind of analogy between the personal and the institutional.

If we're not able to sort of acknowledge the sometimes profound and irreparable damage that we've inflicted,

Then there seems to be a good chance that even the avoidance of acknowledging it is going to lead to the infliction of more brutality,

More damage.

I was wondering if you would be willing to read a passage from the final chapter of your book on gratitude.

Oh yeah,

I'd love to.

This is a passage from the last chapter that's called,

The last incitement called joy and gratitude.

The luminous mycelial tethers between us,

Our fundamental connection to one another,

The raft through the sorrow,

The holding through the grief joy is,

Reminds us again and again that we belong not to an institution or a party or a state or a market,

But to each other.

Needfully so,

Which we must practice and study and sing and story and dream and celebrate.

Belonging to each other as though our lives depended on it.

Beautiful.

Thank you.

Could you say just a little bit more about joy as a practice of resistance and of belonging?

Joy is so powerful.

It reminds us that we can belong.

I feel like culturally,

There's a kind of profound alienation that people are feeling.

I feel like joy itself is the evidence of a feeling of belonging.

And that feeling of belonging can be heartbreak.

It can be a kind of mutual heartbreak or gathering around,

You know,

All kinds of things,

But it does feel like it is the evidence of the belonging to one another,

The evidence of a feeling of belonging.

And that,

That feeling of belonging incites more stuff by which we understand we belong to one another.

The important thing that I'm finding is I want to be able to articulate all these ways that we do this daily in simple ways.

I want to be able to sort of articulate and notice the ways that walking down the street,

Going to get my coffee or whatever,

I'm in the midst of a kind of remarkable care,

A kind of daily care.

The practice is noticing it and articulating it and saying,

Oh,

That's one of the ways we do this.

And I'm curious,

What brings you joy these days?

You know,

I just had like a four and a half hour meeting with a student who's doing like an honors thesis,

Undergraduate thesis.

And it was so lovely to see this kid go from writing poems,

What she was writing poems like at the beginning of the year,

To now watching this kid read a lot of stuff and meet other poets and work on their craft and to see how sort of delighted she was.

It was so lovely.

It was so dear.

That's one thing.

Being with students is kind of a lucky daily thing for me.

The other thing is that I've been torn around with this book a little bit,

Giving a lot of readings.

I love giving readings.

I love being in rooms with people.

And I love the sort of generosity that the people at these readings have.

I have these conversations where I come to understand more like what I'm thinking about and changed every single time that I do it.

It kind of feels like an entry into joy doing that too.

Well,

This episode has given me a lot of joy.

So,

Roskay,

It's been a pleasure.

Thank you.

Thank you so much for joining us.

For our listeners,

Be sure to pick up a copy of Inciting Joy,

Available now.

We like to close these podcasts with a short guided meditation.

So I'll hand this over to Sharon now.

Well,

I'm feeling a lot of joy as well.

Why don't we sit together for a few minutes,

Close your eyes or not,

Just be at ease.

Start just by listening to sounds.

It could be the sound of my voice or other sounds.

It's a way of establishing a kind of big space in our awareness.

Sounds come and go.

Some we like,

Some we don't like.

But we can just allow them.

Feel your body sitting,

Whatever sensations you discover.

See if you can feel the earth supporting you.

And feel space touching you.

Something I learned as teachers would suggest that instruction and we would all like pick up our fingers and poke them in the air,

Is that space is already touching us.

It's always touching us.

We just need to be able to receive it.

And feel your breath,

Which is really the life force,

Just a normal natural breath,

Wherever you feel it most distinctly,

Nostrils,

Chest or abdomen.

You can find that place.

Bring your attention and just rest.

This breath is not only our own life force,

It's that which connects us,

Each of us in this world.

And with the greatest of appreciation for our time together,

You can open your eyes or lift your gaze and we'll end the meditation.

Thank you so much,

Sharon.

And thank you again,

Ross.

It was a real delight.

Thank you.

It was lovely to talk with you both.

You've been listening to Life As It Is with Ross Gay.

We'd love to hear your thoughts about the podcast.

So write us at feedback at trischool.

Org to let us know what you think.

If you enjoyed this episode,

Please consider leaving a review on Apple Podcasts.

To keep up with the show,

You can follow Trischool Talks wherever you listen to podcasts.

Trischool Talks and Life As It Is are produced by As It Should Be Productions and Sarah Fleming.

I'm James Shaheen,

Editor-in-Chief of Prisicle The Buddhist Review.

Thanks for listening.

5.0 (31)

Recent Reviews

Kathi

April 18, 2024

Uplifting and inspiring ! Thank you 😊

Monica

December 29, 2023

Very refreshing views and perspectives. Will share with others and wondering if you have something for high school students? Namaste 🙏🏽

Marie

April 7, 2023

I connected to so many elements of this talk, it was wonderful! The gift of sharing « the bounty » with others, be it zucchini, our shared interest in gardening, our resistance to acknowledge our sorrow/fear … and the joy of connecting with another person/s… Sharing excitement, frustration at the last frost killing our budding plants is often a « safe way » to connect with ourselves and others… clearing a path to intimacy… testing the safety of those relationships and capacity to hold and be held with tenderness, experience the flow of sympathetic joy. - A wonderful interview, with everyone sharing the delight in each other. Thank you!