Frank Ostaseski: Learning To Live Fully

by Tricycle

A pioneer in end-of-life care, Frank Ostaseski brings his Buddhist practice—and a startlingly respectful compassion—to the bedsides of people who are face to face with dying. In his new book, The Five Invitations: What Death Can Teach Us About Living Fully, he has learned lessons that “are too important to be left to our final hours”: By turning away from death, he says, we also turn away from the preciousness of life and our ability to live fully.

Transcript

Hello and welcome to Tricycle Talks.

I'm James Shaheen,

Editor and publisher of Tricycle the Buddhist Review.

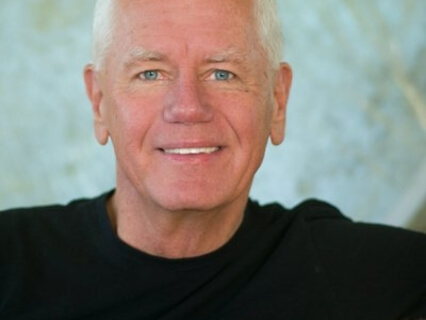

Frank Ostasecki is the author of a new book,

The Five Invitations,

Discovering What Death Can Teach Us About Living Fully.

Frank is co-founder of the Zen Hospice Project in San Francisco,

The first Buddhist hospice in America,

And founder of the Meta Institute in Sausalito,

California.

For the past three decades,

Frank has sat with people in their dying process.

The lessons he has learned over the years inform his wonderful new book.

Amy Gross is a contributing editor at Tricycle.

In this interview,

She talks with Frank Ostasecki about the five invitations he's observed and lived in his time spent with people who are dying.

Frank,

You're writing about your experiences at the Zen Hospice Project and describe your work as being a compassionate companion to people who are dying.

And these truths you say,

What you've learned,

Are too important to be left for our final hours.

It's an amazing book about fear,

Pain,

Suffering,

Transformation,

Mystery,

And love,

Boundless love,

Love as the essence of who we are.

And everyone who is going to die or who loves someone who is going to die should read it again and again.

The five invitations are wisdom itself,

And they are threaded together with stories that I read the way a novice tennis player would watch videos of a pro playing.

Well,

First I want to just say thank you for doing this.

It's really kind of you to do this,

And I'm very glad that we get to share this with a big audience of people.

Yes,

Me too.

Because as you suggested,

Death comes to all of us.

None of us get out of here alive,

Right?

And it's a ridiculous gamble to wait until the time of our death to learn the lessons it has to teach.

To imagine at that point we will have the strength of body,

The emotional stability,

The mental clarity to do the work of a lifetime is absurd.

And so we have to practice now.

We have to see now what our relationship is to these issues.

And then we can step into our life with both feet.

Then we can really embrace our life and savor it and taste every bit of it.

So when I'm with dying people,

Or people who are dying I should say,

I just try to be myself.

There's the story about the woman who is dying of breast cancer who decided that she wanted to get married.

Can you tell us what your response was?

This story that you're referencing is a woman weeks from death who decides that she wants to be married and she wants to get married to her partner.

And I somehow intuitively understood that when you're getting married at this stage of your life,

It's not just about a wedding ceremony.

You're trying to really touch something much deeper,

A deeper sense of belonging,

I think.

She asked me if I would perform the ceremony.

I said,

Yes,

Absolutely.

But what I really think you need is a wedding coordinator.

And I'm very good at that.

I could do that.

And so she agreed and we set about every day talking about the wedding.

What it would be like,

Whether she would be in her bed or sit in a wheelchair.

What would her vows be?

What kind of cake did she want?

Was it chocolate or vanilla?

And then one day in the middle of one of those discussions about cake,

She just burst into tears and she said,

I just want my mom to be there.

Now,

When we're really trying to be compassionately present for someone,

We have to tune into what matters most to them in this moment.

What's the exact face of their suffering?

And in this moment,

It wasn't the fact that she had cancer or the fact that she was dying.

It was that she was getting married and she wanted her mom to be there.

Yeah.

That was the face of her suffering that day.

And that's what we had to meet.

Now,

I could have ridden over it and said,

Oh,

That doesn't matter.

But it did matter.

It really mattered a lot.

And so I had to ask her,

How can we have your mom here?

She said,

Well,

She used to write poems and she would have read one at my wedding.

I know she would have.

Her mother had died many years before.

And she said,

Would you read it?

And I said,

Oh,

I'd be honored to read it.

Of course.

And that's the way we went about it.

Keep it simple.

When we're with people who are at the end of their life,

Keep it simple and be real.

And what's going on with you?

I mean,

Here you are.

I was thinking the moment when she'd say,

Oh,

I want my mom.

And I think most people would have said,

Oh,

I'm so sorry.

She's not here for you.

But you didn't.

It's such an un-clichéed response.

How can we bring your mother's presence here?

Yeah.

Well,

People are expressing a need.

So for me,

I think it's having a sense of curiosity,

Really being open and having a sense of wonder,

Like,

What's this going to be like,

This encounter,

This person?

And so I try to keep an open,

Fresh way of being with people.

You're also hearing them as you're not just writing them off as a dying person who has no future.

Yeah,

I don't even like this phrase,

The dying,

Because there is no the dying.

There are just people who are going through a dying process.

And dying is not who they are.

It's what they're going through.

And so there's a whole human being there.

And we have to meet that whole human being.

Right.

And,

You know,

In this case,

It was a whole human being who was getting married and wanted her mother to be present and waiting.

So you throughout the book,

You've said little clues to me when I think to myself,

What's going on in you during these encounters?

What would you teach me to do?

You've said my primary goal is to stay in the room and to keep my heart open and watch your mind.

Watch your mind,

Open your heart.

Yeah.

Another way to say it is let your mind drop into your heart.

And for me,

That's sincerity,

Genuinely wanting to be present.

I train a lot of clinicians,

Including among them,

Many psychologists.

And I always explain to them that I have one intervention that has been most useful for me.

And it could save them thousands of dollars in educational bills.

And that is I walk in the room and I sit down.

Because when I sit down in the chair,

I'm less likely to run away,

Actually,

Even though there's a whole part of me that wants to run away.

You know,

I get scared in those rooms.

I don't always know what to do.

But if I stay still,

If I keep my feet on the ground,

If I keep my butt in the chair,

Then something innate in me will emerge.

I think it's my innate compassion that will come forward and guide me,

Really.

That's how I think about it as a kind of guidance.

You know,

Compassion isn't just a warm and fuzzy feeling.

It's guidance from the deepest part of our nature that shows us what's necessary and how to respond.

So you've mentioned the word fear.

I see fear as a moat around the subject of dying,

Of the death process.

And a friend of mine who just recovered from surgery,

I was telling her I was doing this interview,

And she said dying well has to do with not being afraid,

Right?

I don't know that I would agree.

First of all,

I'm not quite sure what this means,

Dying well anymore.

You know,

There's all this rhetoric in the culture about a good death,

You know.

And I think these are sometimes ideas that we use to comfort ourselves.

But oftentimes they can be an awful big imposition on the person who's actually dying.

We even have a way that we want to choreograph their death.

Fear is OK with me.

I'm a little suspicious,

Actually,

Of people who say they have no fear of dying.

I still do.

And I've been around it a lot.

What I think is helpful is to recognize that when they're afraid,

They know they're afraid.

And that means that some part of me is not afraid.

And I can function from that.

I can be in the world in a realistic way from that awareness.

So it's not that there's no fear.

It's just that fear is not the only thing in the room.

We can cultivate our capacity for that and learn to have a wise and even warm relationship with our fear.

When I think of the way the people you sit with are dying,

It seems so fortunate to me compared with what we see the technological,

Medical,

Corporate deaths that we see on television and read about all the time,

People wired,

Numb,

Sliding out of life in unconsciousness.

Your people seem so alert,

Conscious,

Deliberate,

Aware.

It seems ironic that they're mostly poor people,

Aren't they?

When we started Zen Hospice,

We had a very simple idea.

It was to put together people who were cultivating what we might call the listening mind or the listening heart in meditation,

Together with people who really needed to be heard,

At least once in their life,

Folks who were dying.

In the beginning,

We worked primarily with people who were medically indigent,

Who were often living on the streets,

On park benches and single room occupancy hotels.

But we didn't exclusively work with those folks.

We worked with all kinds of people.

And some of them actually did come to their death,

As you suggest,

With a certain degree of consciousness and making,

Sometimes,

Reconciliations they'd longed for in their whole lives.

But some of them turned toward the wall and withdrawal,

And they never came back again.

I think what we had to learn how to do is to be with all of that,

The whole magilla.

I also work with people in all kinds of situations,

Hospitals,

ICU units.

And there is no one right place to die.

I think that we can create loving,

Kind environments wherever people are.

Now,

Certainly,

It's helpful to have good conditions,

Right?

It's like when we go to a meditation retreat and we have a really nice place.

It's easier to meditate.

But I also meditated in Asia where it was loud and noisy,

And ICUs are loud and noisy.

And yet people can still die there with grace and dignity and the love of their families or of the caregivers around them.

Now,

Having said that,

The primary way we have of measuring death in this country are monitors.

You know,

Those lines that go up and down and the beeping sounds and the heart and rhythm of the breath,

Et cetera.

And then there's that dreaded flat line where it goes completely horizontal.

And there's a long beeping sound.

And I've been with family members who've been watching that monitor waiting for their loved one to die.

And I think there are more intimate ways of being with death than that.

So certainly,

I try to encourage that with the people that I work with and with their families,

You know,

To get up close with death.

To get to know it really personally,

To not be afraid to touch,

To speak,

To kiss,

You know,

To hold,

To really love the people that are in front of us.

One of the techniques instead of the monitor is breathing with.

Well,

You know,

The breath is a beautiful tool,

A diagnostic tool to understand at any one point where we are.

And it's no different in and around the time of dying.

There was a woman in our hospice who I really loved,

Actually,

And she was an old Russian lady,

About 86 years old,

Tough as nails,

You know.

And the night that she was dying,

They called me and I went into the room to be with her.

And my habit when I walk into a room is actually to sit in the corner to see is anything really needed before I jump in to help.

And so sitting next to Adele was a wonderful home health aide.

Pat was very kind to her and she had turned to Adele and she said,

Adele,

You don't have to be scared.

I'm right here with you.

Adele turned to her and flat out said to her,

Honey,

If this was happening to you,

You'd be scared.

So I stayed in the corner,

You know.

And then a bit later,

Pat said to her,

You look a little cold.

Would you like a blanket,

A shawl?

And Adele shot back.

Of course,

I'm cold.

I'm almost dead.

You know.

Now,

I hope when I'm dying that I have half of the tenacity of this woman.

So I noticed two things.

The first was that she wanted complete honesty.

She didn't want to talk about tunnels of light or bardos or any of these things.

She wanted somebody who would be real with her.

And the second was that there was a struggle.

There's a labor to die,

Just like there's a labor to getting born.

And the struggle in her case was manifesting in the breath.

Every in-breath struggle,

Every out-breath struggle.

And this was despite the fact that we'd made all the right interventions.

So I pulled up my chair very close to her,

As close as you and I are sitting right now.

And then I said,

Adele,

Would you like to suffer a little less?

And she said,

Yes.

And I said,

Well,

I noticed something.

I noticed that right there at the end of your exhale,

There was this little pause,

A little gap,

Just before the next inhale.

And I wonder what it would be like if you put your attention there on that gap,

On that little pause.

Now remember,

This is a 86-year-old Russian Jewish lady.

She doesn't care beans about Buddhism or meditation.

But she's highly motivated in this moment to be free of suffering.

And isn't that what gets most of us to go sit on a meditation cushion?

So I sat in front of her and I said,

Go ahead,

Try it.

I'll breathe with you.

I didn't guide her.

I didn't try to show her how to breathe.

I just breathe with her.

It's a very intimate thing to do.

And then after a little while,

I could see the fear in her face just drain away,

Actually.

She relaxed and a little bit later,

She laid back on her pillow and she died a few minutes later quite peacefully.

I think Adele found a place of rest in the middle of things.

You know,

We're always looking to find our rest later.

We go on vacation or retreat or inbox gets empty.

You know,

I think that place of rest is always available to us and we need to find it for ourselves.

You know,

She found it in the exhale and the gap at the end of the exhale.

Where do we find it?

You know,

One of the things that I'm trying to do with the book is share those kinds of experiences.

The wisdom of that moment that's available to us through our whole lives,

You know,

Every part of our life.

And I want people to avail themselves of that wisdom and to try and use it to live a happier and more meaningful life.

So there's a wonderful line.

The one who is not too busy is always available.

And I think of that.

New Yorkers are not the only ones who rush,

But I think we are proudest of our rushing.

But that line has come to,

You know,

Reverberate in my mind.

And I think the one who is not busy and I've also begun to think that the word rest is the most beautiful four letter word.

Thank you for that.

Yeah,

It's an old Zen story,

You know,

Zen con,

The one who's not busy.

And you quote,

Nershal Cameron Porche,

Something that comes to me at least once a day.

Rest in natural great peace,

This exhausted mind beaten helpless by karma and neurotic thoughts,

Like the relentless fury of the pounding waves in the infinite ocean of samsara.

Isn't that the best teaching ever?

I mean,

I just wow,

I'm so grateful to him for having said that.

And so many others have adapted it so beautifully.

So go Rinpoche among them.

It's such a perfect description of this human life.

Neurotic thought.

Boy,

I have a lot of those beaten helplessly.

I sort of feel that sometimes like I'm at the effect of the world.

You know,

To find a place of rest is about relaxing with things the way they are.

We're mostly trying to change the conditions.

You know the old story of people trying to arrange deck chairs on the Titanic that they're missing the big picture,

Right?

And that's how it is sometimes in our life.

Finding a place of rest isn't about,

You know,

Resignation.

It isn't about becoming a doormat.

But it is learning to relax,

You know,

To pause,

To then open.

Really to open to life as we know it.

And then to allow whatever is coming forward to come forward and then to become intimate with it.

I have trouble with these words,

Enlightenment and liberation and awakening even.

You know,

They all feel distant.

They all feel far off to me.

Like I'm trying to learn about something that I don't know.

So I prefer the word intimacy.

Like I'm coming close to something that I already know,

Yeah,

But that I forgot.

So to find a place of rest is taking a step in that direction toward intimacy.

There's an amazing quote from a woman,

A professional doctor I think it was,

Talked about the secret gratitude of newly diagnosed cancer patients.

Now they can say no.

It seemed like the most pointed indictment of the way we live.

Well,

You know,

A good friend of mine,

Angie Stevens,

Who I speak with,

Who's an eminent psychotherapist and weight Buddhist teacher as well.

And we were talking one day about exhaustion.

And how we've been holding it up so long in our lives,

You know,

Keeping it all together,

You know,

Keeping a stiff upper lip and all those cliches.

And she was talking about the patients that she works with with cancer and the relief that they feel sometimes at having gotten the diagnosis.

And I don't mean to,

I'm not trying to be romantic about getting a diagnosis of cancer by all means.

It's difficult.

But there is also something in it in which people say,

Oh,

Finally,

Finally I can stop trying to keep it all together.

Yeah.

Finally,

I can say no.

Finally,

I can just be as I am.

We don't give ourselves that freedom.

We don't give ourselves that permission oftentimes.

And we,

You know,

Drive ourselves relentlessly like the ocean's waves,

Right?

So we've mentioned the fourth invitation,

Which is to find rest in the middle of the thing.

So let's go to the first,

Which is don't wait.

Don't wait.

It's one of my favorites.

You know,

When we're waiting,

We're often filled with expectation,

Waiting for the next moment to arrive.

We miss this one.

You know,

I've been with countless family members who've said to me,

You know,

When will my mom die?

And waiting for the moment of dying,

They miss all the moments in between.

So it's not a kind of encouragement to,

You know,

Live with some kind of urgency or to collect all the toys you can possibly get in this life or all the experiences.

It's an encouragement to be here,

Right here,

Right in this moment,

You know?

It's a kind of encouragement toward constancy,

Toward a constant way of paying attention.

You know,

That's what mindfulness is,

Right?

Mindfulness is constant attention.

So don't wait until the time of your dying to learn its lessons.

And please don't wait to tell people you love that you love them.

You know,

Do it now.

Do you have bone to pick with patience?

Do you want to tell us your argument with patience?

Well,

Just that patience has sometimes still this feeling of I'm waiting for something to come along,

The better situation or I'm holding an idea of myself as a patient person.

And it still has a flavor of this expectation in it,

I think.

And I'm thinking instead of patience as a word,

You talk about mature hope.

Well,

Hope is a complex and difficult idea.

You know,

If you say to someone,

Give up hope,

Which is oftentimes the way it's understood in Buddhist circles.

And I don't necessarily agree with it.

I understand what it's doing.

In many,

Many teachings,

There's a notion that fear and hope are two sides of the same coin.

And I could make a case for that as well.

But I have a sense that we actually need hope.

As a culture,

We need it.

Maybe we need it more now than we ever did.

And so then we have to understand hope.

If we need it,

Then we have to understand something about it.

And we have to delink it or separate it from expectation.

Our hopes are usually about a particular outcome,

A particular expectation.

And I think hope is something different.

I think hope is about entering this moment so fully and completely that we understand that the future and the past are in this moment.

It's not that there's no future or past.

There is future and past.

It's just whole here.

The potency for the future lives here.

I have a granddaughter who I love dearly.

She's a year and a half.

And I can see in her tremendous potency for a whole life.

I have no idea how it's going to turn out.

And I don't have an expectation about what she should do with it.

But in her,

I can see the potency,

The innate beauty that is part of her being.

And I have hope in that potency.

So in the section on Don't Wait,

You're pointing to,

First you have Seung-San and his remark,

Frequent remark,

Soon Dead,

To remind us.

And the lines of,

Be aware of the great matter of birth and death.

Life passes swiftly.

Wake up.

Wake up.

Do not waste this life.

And I'm struck by how hard it is,

Maybe impossible,

To remember death.

I wonder if our brains are just wired,

Not,

I mean,

Unless you're doing your kind of work daily,

Daily confrontation with that reality,

It's really hard to hold on to.

Well,

I agree.

I think it is hard.

I think that we've got millennium of DNA conditioning to keep death at arm's length.

And so I think it is difficult.

I think this is why Buddhist practice holds death as such an important reflection.

It's why the Benedictines kept skulls on their desk,

To remember that this is part of our experience.

And in my mind,

It's not just the part of our experience that happens after a long road of life,

But that it's in the very marrow of our everyday experience.

And it's a little bit easier to see it there,

Actually,

The constant coming and going of things,

The arising of this moment and the death of this moment.

Now,

Our ego self,

Our sense of separate self,

Can't really prepare for its dying.

It's too scared.

Who I am,

Little old Frank,

I can sort of decide between vanilla and chocolate ice cream or something like that,

But I can't really make the big decisions.

For that,

I need something more expansive.

I need to be in contact with a deeper dimension of who I am.

My ego self,

If you will,

We're going to use that term loosely,

But it's built on imitation.

As a child grows,

I'm watching it with my granddaughter now,

They imitate what they see.

And then that imitation becomes part of who they are,

Becomes the personality.

The sense of self-image that we put forward in the world.

But something in us knows that that's inherently unstable.

And so we have to understand that it's not the wisest voice in the room and that we maybe shouldn't let it guide every dimension of our life.

For that,

We need to become more discerning and utilize discriminating wisdom that we speak about in Buddhism to guide our lives and to help us do something almost unimaginable,

Which is to prepare for our dying.

Another technique that you use is generous listening.

And there's a quote of Carl Rogers,

Who you credit as an influence on you.

You say,

His listening was so devout,

It drew out the truth.

And Carl Rogers was describing some man whom you would think he'd have no way to identify with and he said,

I too am vulnerable.

And because of this,

I am enough.

Whatever his story,

He no longer needs to be alone with it.

This is what will allow his healing to begin.

It's so touching,

Not only for Carl Rogers' compassion,

But it feels like it enables each of us to say we can take that on.

I too can be enough.

First of all,

Carl was a genius at listening.

And if we're going back and watch some of his old films that they made of him,

And you can see he says almost nothing often when he's with people.

He just listened so devoutly that he would draw the truth from them.

And then he didn't analyze them.

He just received.

I think we really underestimate the power of simple human kindness.

The generosity in that kind of listening is healing.

We are enough.

We have to remember that long before we had some of the sophisticated techniques that we currently have available to us,

And they're very helpful,

Of course,

We just had each other.

This isn't in the book,

But a woman I trained was the executive director of the National Hospitals in Slovenia.

And she was invited to go to Croatia and Bosnia not long after the horrible devastation there and the wars there to speak about grief with a group of workers.

And she arrived imagining she would be speaking to a group of about 30 people.

But instead what happened was 500 people showed up,

500 people who had lost relatives whose families had been split apart,

Devastated,

Torn apart by war.

And they were traumatized.

And she thought,

What can I do?

What can I say to them?

And so she did this very simple and beautiful thing.

She had them listen to each other.

She just put them into pairs and then the triads and then the small groups,

And she just had them listen to each other.

To allow someone to pour out their suffering and to be listened to without advice,

Without counsel,

Without strategies.

Just to be received and to have what's offered held.

This is an enormous gift.

I think it's the shortest route between two people,

Our capacity to listen to each other.

That's brilliant.

I'm just so.

.

.

Yeah,

I was amazed by her presence,

Her ability to be so presence and creative in that moment.

And I think she used a kind of discriminating wisdom.

She used.

.

.

She put aside her papers and her talk and what she imagined and she met what was in front of her.

So the second invitation,

Welcome everything,

Push away nothing.

Sounds pretty good,

Huh?

I'd make a great bumper sticker.

Yeah.

So it goes back to I am enough.

Do you know what it is that's gonna wake you up in this life?

I don't.

I mean,

I do my practices and I pay attention to my teachers and I do my very best to stay present.

But honestly,

I don't know what's gonna wake me up.

And so I have to pay attention to everything.

Think of all those end stories of bamboo cracking and monks being liberated in those moments.

Of course,

Those stories never tell you that the monk had been practicing on their cushion for 30 or 40 years before then,

You know,

Sudden and gradual enlightenment.

So to welcome everything,

It sort of challenges us,

You know,

Challenges us to set aside our judgments when we say welcome.

I was struck by your saying,

The self-critic stops all growth.

Yeah.

What's your best way of defending yourself against the self-critic?

I think there's numerous ways and we have to sort of see what's appropriate to the nature of the attack.

You know,

One way that I speak to myself or to my own critics sometimes is just to say,

Ow,

That hurts when you speak to me that way.

Don't speak to me that way.

You know,

It hurts too much,

You know,

And so to kind of acknowledge the emotional effect of this critical statement.

Sometimes I use strength.

You know,

I say back off,

Critic,

And I borrow the aggression that's coming from the critic and I use it in my own defense.

And I find in my anger,

Strength.

You can feel it when you get angry sometimes.

The body gets tight,

The spine,

You know,

Gets contracted.

That's not so helpful.

But if you look a little more closely and just stay with the energetic quality of it,

You find that there's a lot of strength in anger.

And we need that strength.

We need that strength to separate,

In this case,

To separate from the critic.

So I think that's a skillful use of anger and of the strength that's hidden within it.

Yeah.

The third invitation is to bring your whole self to the experience.

No part left out.

We're always editing ourselves,

Aren't we?

Trying to perfect some notion of who we should be or how we should look.

Look,

We all like to look good.

We all like to appear smart,

You know.

We all want to be beautiful.

But we are who we are.

And I think it's really important that we come to a kind of allowing and full acceptance of just who we are and bring that forward.

And then when we do that,

We bring our whole humanity forward.

There's a quote in this section that had me writing.

This is the big secret,

Isn't it?

And it's about vulnerability,

How scary that is.

And at one point you say,

We live in a shell of invulnerability and grief,

Which is unpredictable,

Unmanageable,

Cracks it.

It exposes the truth,

Our human frailty.

And then you're going to talk about the paradox that the being with vulnerability,

Undefended,

Is how we find our invulnerability,

Something invulnerable in us.

Yeah.

Vulnerability is scary.

And it's scary because we have it mostly tied up with fragility and dependence,

Helplessness,

Or the possibility that we can be harmed.

What we usually encounter when we think about it that way is all our defenses against vulnerability.

Vulnerability itself is just open.

It's porous.

I was teaching a workshop for docs and nurses on compassion,

And in the course of it,

I had a heart attack.

And this resulted in triple bypass surgery and many,

Many months of healing.

And in the course of that experience,

I felt very,

Very vulnerable.

And it scared me.

It really scared me.

I couldn't do anything.

I couldn't shower myself.

I couldn't use the toilet by myself.

I needed people to help me with everything.

But gradually,

As I allowed it,

I began to experience myself as something more tender,

Less rigid.

And I found there,

In that porousness,

An ability to really receive the world in a way that I had been familiar with before,

But I became much more intimate with.

And it had to do with receiving both the beauty and the horror of this world and letting it all impress itself upon my soul,

Upon my being.

And I think this is something that's particularly unique to human beings,

That we have this capacity to know the most sublime and the most awful of aspects of reality.

And what enables us to do that is our ability to allow it to impress itself on us.

And that can only happen if we allow for this kind of vulnerability that I'm speaking of here,

Which is a kind of openness,

A receptivity,

In a way,

A kind of innocence.

The fifth invitation is cultivate don't-know-mind.

Yeah,

I sort of felt like I should put something Zen-like in the list.

What does that mean,

Cultivate don't-know-mind?

I remember once giving my son,

When he was a teenager,

Zen My Beginner's Mind,

And he was reading some parts of it that had to do with the Heart Sutra,

You know,

There are no ears,

No eyes,

No mouth.

I came downstairs and he looked at me with utter confusion.

He said,

Dad,

What the hell are they talking about here?

This is what you teach?

I don't understand it at all.

And so when we say cultivate don't-know-mind,

It's a little bit confusing for us.

It sounds like we're saying let's cultivate ignorance,

But it's not an encouragement of ignorance.

We know stuff.

It's good that we know stuff,

But it's also good to put what we know in the context of all there is to know.

And then we can understand that there's a lot of stuff we don't know.

Ignorance is not exactly not knowing.

Ignorance is actually that we know something really,

Really well,

But it's the wrong thing.

To not know means I don't use my knowing to kill this moment.

I don't clobber the moment with all my knowing,

All of my expertise,

All of my,

You know,

I walk into a room where someone's dying.

I don't know.

I don't know what they need.

I don't know.

I think they might know,

But I certainly don't.

And so I have to walk into that room with a don't-know-mind to meet what's in front of me with wonder,

Curiosity.

My advice is not going to help them,

You know,

Even the best of my good counsel.

So to cultivate don't-know-mind is to cultivate a mind that's willing to be intimate.

You know,

When we walk into a room and it's dark,

You know,

We have to feel our way around for the light switch,

Right?

I call it using the Braille method.

You know,

I feel my way through the experience.

And so,

You know,

In Zen we say not knowing is most intimate.

Yeah.

Dogen described it as not knowing is nearest,

He said.

It means it's the closest thing I could say to what the experience of enlightenment is.

Yeah.

So you talk often about death not being just a medical event,

But this process of transformation.

People get to be transparent,

They become radiant.

And one of these people is Sono,

Who seemed to be very matter of fact.

You thought you were going to enjoy working with her.

You know,

I have a photo of her at the hospice,

Taken two hours after she came in the door,

And it's her fist in front of her face,

Unbelievable determination.

And then I have a series of photos of her that show her writing in her journals,

Looking out the window and reflecting,

Coming forehead to forehead with one of our volunteers in a very intimate moment.

And then I have a photo of her shortly after she died,

Two hours after she died,

Very peaceful.

And pinned to her bedclothes is her death poem.

One afternoon we were sitting in the kitchen at the hospice,

And I was reading a book of Japanese death poems.

And you know,

There's a tradition in Japan amongst monks and others,

That you write a poem on the day of your death that tells the essential truth of your life.

How awake do you have to be then,

Right,

To do that?

So anyway,

I was reading this book of poems,

And Sono asked me about them.

And she said,

I want to write one of those.

And I said,

Okay,

Great.

She said,

What's the form?

I said,

I don't know,

Worry about the form,

Just you write it.

So she did,

And several hours later,

She called me up to her room and she said,

I've written my death poem.

She said,

I want you to learn it by heart.

I want it to live in your soul.

Would you read it for us?

No,

But I'll recite it for you.

Oh,

Thank you.

Don't just stand there with your hair turning gray.

Soon enough the seas will sink your little island.

So while there is still the illusion of time,

Set out for some other shore.

No sense packing a bag.

You won't be able to lift it into your boat.

So give away all of your collections.

Take only new seeds and an old stick.

Send out some prayers on the wind before you sail.

Don't be afraid.

Someone knows you're coming.

An extra fish has been salted.

Thank you.

Thank you so much.

You've been listening to Amy Gross in conversation with Frank Ostoszewski about his new book,

The Five Invitations,

Discovering What Death Can Teach Us About Living Fully.

If you'd like to share your thoughts with us,

Email us at feedback at tricycle.

Org.

Tricycle Talks is a production of the Tricycle Foundation,

Publisher of Tricycle,

The Buddhist Review.

This episode was produced by Cary Donoghue and recorded and mastered with Paul Ruest at Argo Studios in New York City.

For all of us at Tricycle Magazine,

I'm James Shaheen.

Thanks for listening.

And we'll see you next time.

Bye.

Bye.

4.9 (562)

Recent Reviews

Nina

March 25, 2025

Wonderful discussion. I learned so much about living and dying from this wise, compassionate man. 💛🙏🏽

MSP

October 4, 2024

Excellent! Thank you, Frank.

NicoleLee

June 15, 2023

Everyone single one of us needs to listen, listen, listen to this.

Rev.

May 22, 2023

I love the absolute honesty and touching truth revealed in this conversation. I bow deeply to you for your service. I would love to air your talks on my radio station in Sedona. If you are interested you can email me. I’m Cindy Paulos Cindy@mauigateway.com

Dan

January 23, 2023

Very interesting... deep yet simple, honest and open. Thank you 🙏

Lee

July 21, 2022

Amazing and profound, yet presented with a gentleness. So much here. Will return. Many thanks and many Blessings 💜🕊

Millie

May 7, 2022

Grateful to have come across this track. Happen to be currently reading his book. Much to take home. 🙏🏽

Pat

April 29, 2022

This was soo profoundly powerful & Soul searching. It made me think about an important decision I had to make about my own life. Soo thought provoking. Thank you soo much for all the beautiful lessons about LIFE.

Kim

February 4, 2022

Excellent. Enlightening. Educational. Emotional. Empathetic. Energeticically enticing.

Teresa

January 21, 2022

Thank you for this tender, enlivening, soul inviting talk. My heart trembles with gratitude. Sending good wishes.

Jill

April 7, 2021

Just beautiful. I've learned so much from Frank and his book, The Five Invitations. It is the first book I've been able to read all the way through since my son Austin ended his life 4 years ago.

Elaine

October 22, 2020

Thank you 🙏🏻❤️

Evelyn

February 10, 2020

These five invitations are inspirational. 🌸🌺

Anna

October 27, 2019

Amazing! I can’t wait to read the book. Thank you!

Mel

October 26, 2019

Rewarding listening. Gentle, compassionate and calming. Thank you for opening new doors of awareness.

Elizabeth

October 26, 2019

WOW... I have already read the book, but hearing his voice is so impactful... 🙏 thank you for sharing your wisdom teachings with us, Frank❤️

Sheila

October 26, 2019

Thank you for this beautiful talk this morning. I will listen again to this. As I approach my 80th birthday this topic is often on my mind, not in a morbid sort of way. Death is not often discussed among family and friends in our society. It’s good to be prepared for any journey we’re going to take. ❤️❤️❤️ with much gratitude.

Randi

October 26, 2019

So powerful. Thank you.