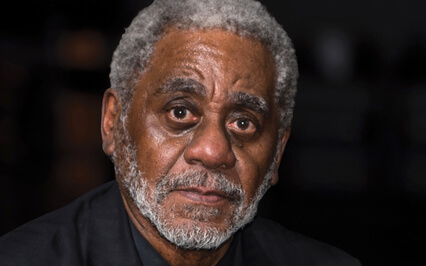

Charles Johnson: How Art Can Liberate Our Perception

by Tricycle

In this episode of Tricycle Talks, Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, sits down with novelist, essayist, screenwriter, professor, philosopher, cartoonist, and martial arts teacher Charles Johnson to discuss his path to writing, how Buddhism finds its way into his work, and why he believes that art should liberate us from calcified ways of thinking and seeing.

Transcript

Hello and welcome to Trischool Talks.

I'm James Shaheen,

Editor-in-Chief of Trischool The Buddhist Review.

Charles Johnson is a novelist,

Essayist,

Screenwriter,

Professor,

Philosopher,

Cartoonist,

And martial arts teacher.

And he's also a Trischool Contributing Editor.

Over the course of his career,

He has published ten novels,

Three cartoon collections,

And a number of essay collections that explore black life in America,

Often through the lens of Buddhist literature and philosophy.

In the February issue of Trischool,

Johnson published a short story called,

Is That So?

,

Which is a contemporary retelling of a classic Zen tale.

In today's episode of Trischool Talks,

I sit down with Chuck to discuss his path to writing,

How Buddhism finds its way into his work,

And why he believes that art should liberate us from calcified ways of thinking and seeing.

So I'm here with novelist Charles Johnson.

Hi Chuck,

It's great to be with you.

It's wonderful to talk to you again.

So you've worked as a novelist,

Essayist,

Screenwriter,

Professor,

Philosopher,

Martial arts teacher,

And Trischool Contributing Editor.

And I remember once I asked you,

Do you ever sleep?

But before all of that,

You started out as a political cartoonist.

How did you get started in cartoons?

I started publishing as a cartoonist when I was 17 years old.

I could draw when I was a kid.

In elementary school,

It was my passion.

And I came under the wing of a well-known cartoonist at the time,

Lawrence Laurier,

And took his two-year correspondence course.

And when I was 17,

I started publishing.

The first thing I published were a series of illustrations for a magic company in Chicago.

But I was publishing in my high school newspaper as well.

And so for seven intense years,

I devoted myself to being a cartoonist,

An illustrator.

A lot of my work was in the black press at the time,

Publications like Jet Magazine and Black World,

And also the Chicago Tribune.

I was an intern there for a while.

It was a passion for seven years.

And there's a new book out now called,

All Your Racial Problems Will Soon End,

The cartoons of Charles Johnson.

I just learned today that it was selected by NPR as one of the best books of 2022.

So that was my early life.

I majored in journalism as an undergraduate,

Which gave me a chance to draw and write.

But it was in journalism that we had to take a required course in philosophy.

And that was the beginning of a new passion for me.

I was introduced to logical fallacies,

Which I'd heard all my life but didn't have a name for,

And also the philosophies of the pre-Socratics.

I was seduced.

So I decided that after I was finished with my journalism degree,

I would stay in school,

Get my master's degree in philosophy,

And then ultimately my doctorate in philosophy.

That's Western philosophy.

I focused on continental philosophy or phenomenology.

But very early in my life,

I was exposed to Eastern philosophy,

Buddhism.

I first practiced meditation when I was 14 years old.

It was one of the most powerful experiences I've ever had.

But I decided,

Since I didn't have a teacher,

I would study Eastern philosophies all the way through my undergraduate years.

It would be my secret pleasure.

But what happened is I ultimately had to get back to meditation.

I've been meditating now for 42 years as of this year.

Find the right teachers and take my vows,

Which I did in the Soto Zen tradition in 2007.

So Buddhism has been a part of my life since my earliest teens.

Tom How did you come upon Buddhism at age 14?

David Well,

My mother was a great reader.

She was in three book clubs,

And she got a book on yoga.

And I looked at it,

And there was a chapter on meditation,

And I was a pretty smart kid.

So I decided,

Let me try this for a half an hour.

At 14,

It was one of the most incredible experiences I've ever had.

And when I got up from that 30 minutes,

I discovered I had been living utterly in the present moment.

Wasn't thinking about the past or thinking about what I was going to do in the future.

I felt compassion for my parents and for my friends.

I felt extremely peaceful and in the present moment.

So I spent a lot of time academically studying Eastern philosophy,

And then came back to meditation and the Dharma.

Tom So it was a year later at the ripe old age of 15 that they began to pay you to illustrate a magic catalog?

David 17.

You can't see my study here,

But I have one of the dollars from that first sale.

And there were times when I was tempted to spend that dollar,

But I didn't.

So yeah,

My first sale was in 1965.

Tom Wow.

So later,

When you heard Amiri Baraka give a talk in 1969,

You were inspired to create a series of cartoons depicting black life in America.

Can you share more about how you view cartoons as a political tool and how this has shaped your work as a writer and artist more generally?

David I did every kind of comic art that you could imagine.

The cartoons in the new cartoon book,

Those are single panel gag cartoons.

But I worked as an editorial cartoonist for the Southern Illinois newspaper when I was an undergraduate and for my college newspaper.

And again,

I was trained as a journalist in the literary circles,

English department circles.

They sometimes dismiss the visual arts because they don't have the background or training in them.

But comic art has an influence on popular culture that cannot be measured.

We have had political cartoonists of note who had impacts on politics like Thomas Nast challenging Tammany Hall in the early 20th century.

I've often said that a really well-drawn cartoon with a really good idea behind it can be experienced like a haiku.

In a moment,

It can give you a revelation.

It can show you something that you had not seen or thought about concerning a situation,

Political or otherwise.

Peter You mentioned twice,

All your racial problems will soon end,

Which was quite popular and was covered in the mainstream press.

What has it been like to look back at your earlier work?

Has it given you any insight into how political art has changed over time?

Because certainly it has.

David Well,

When I look at the 250 cartoons in that book,

I realize I don't remember doing some of them.

It was so long ago,

Over 50 years ago.

Now,

The book does cover early work and some recent cartooning that I did for Tricycle,

Some of these Zen cartoons and Buddhist cartoons.

But some of the earlier work,

I look at it,

I thought,

What was I thinking?

Now,

Back in the late 60s and early 70s,

You have to realize it was more free-wheeling in the early 70s.

You had comedians like Richard Pryor.

You had shows like All in the Family.

You had a lot of comedians who would just go for it.

People didn't feel offended.

But as the decades have rolled along,

I find today that people are extremely sensitive and wear their feelings on their sleeves.

I think this is sad.

Peter Do you feel the constraints yourself?

Has it held you back at times when you wanted to do something,

But you said,

You know what,

People are going to respond and get very upset?

Never.

A good journalist does not believe in sacred cows.

If a subject is worthy of exploring as a drawing,

As a short story,

As a novel,

The artist has an obligation,

I think,

To go for it.

How did you go from being a cartoonist,

Among many other things,

To writing novels?

You've published 10 works of fiction.

They seem like two very different media,

Different ways to express yourself.

How did this happen?

Well,

All the arts are related.

All of the arts are interconnected.

Just as we would say in Buddhism,

Everything is interconnected.

I was a big reader too.

All the way through high school,

I made myself read at least one book a week that had nothing to do with my schoolwork.

And some weeks it became two,

And some weeks it became three,

Because reading stories fed my imagination as a cartoonist.

In the late 60s,

All my friends were involved in the arts in one way or another.

I had friends who wanted to become the next Beatles and the next Rolling Stones.

I had another friend who wrote six novels that never got published.

We collaborated sometimes on comic strips for our college newspaper.

So I was in an environment that was bubbling with creativity.

So it happened one day that I had an idea for a novel.

It was around 1970,

I guess,

And it wouldn't let me sleep at night.

I'd keep thinking of scenes,

And so the only way to get rid of it was to sit down and write it,

Which I did over a summer.

And it was written too quickly,

But it was the beginning for me of novel writing.

I wrote six novels in two years.

With each novel,

I tried to improve.

If in the first novel,

Characterization was not working or plotting or description,

In the next one,

I tried to improve on those matters.

After six novels in two years,

I found myself coming into the orbit of novelist John Gardner,

Who was just on the rise at that time,

1972.

He'd published a critically acclaimed novel called Grindel,

And his first bestseller was The Sunlight Dialogues in 1972.

John took me under his wing.

I knew nothing about the literary world.

And I wrote the next book,

The seventh book,

Which is my first published book,

Faith in the Good Thing,

In nine months with him looking over my shoulder.

And I thought that was an incredibly long period of time to do anything.

Nine months working on something?

I was talking to my friend,

Editorial cartoonist David Horsey,

Who's a two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist.

He's written a novel recently,

But he said to me he was used to instant gratification.

You do a drawing,

It's in the newspaper the next day or two days later.

With a novel,

No,

It's a little bit different.

So I spent nine months on my first published novel,

Faith in the Good Thing.

But after that,

I began to realize what was at stake with every novel that I did.

So the next book,

Ox-Herding Tale,

I spent five years on it.

The next book,

Middle Passage,

Which received the National Book Award,

I'd spent six years on that and did a ton of research on the slave trade.

And the book after that,

Dreamer,

I spent seven years studying Martin Luther King in every way that I possibly could.

Two years of research just before I wrote the first paragraph.

David Page You write about Faith in the Good Thing that your aim was to enrich the tradition of,

Quote,

African-American philosophical fiction.

Can you say more about the genre?

Richard Davis Well,

I'm working on a response right now to a magnificent book recently published by Richard Schusterman.

The book is called Philosophy and the Art of Writing.

It's something I would recommend to everyone.

It's a seminal book.

Those disciplines,

Philosophy and literature,

Have been united since the time,

Really,

Of the ancient Athenians.

If you look at Plato's dialogues,

They are dialogues.

They occur in a dramatic form.

If you look at Plato's other dialogues,

He has stories and anecdotes.

In the West,

For the last 2,

000 years,

You will find writers who understood instinctively that philosophy and literature were sister disciplines.

Wordsworth,

As a poet,

Understood that.

Augustine understood that in the Confessions.

T.

S.

Eliot truly understood it.

We have a tradition of what is called philosophical fiction and philosophical poetry.

But in America,

I hate to say it,

We have had currents of anti-intellectualism.

So we don't find that many people who have devoted themselves to the philosophical questions.

In our time,

I think John Gardner was one of those people,

Especially with his novel,

Grindel,

Which is a kind of send-up of Sartrean existentialism.

We also saw Bellow.

I like to think there's philosophical dimensions of importance in Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man.

And when I say philosophy and literature,

I mean traditional philosophical questions that try to come to some degree of clarity,

But not a final solution with questions of epistemology,

Political philosophy,

Ontology,

The old traditional questions of philosophy.

Every one of my novels has a core philosophical question at its center.

Faith in the Good Thing,

The question is,

What is the good?

That's Plato's old question.

Ox-Herding Tale,

The question at the center of the novel is,

What is the self?

In Middle Passage,

The question is,

Where is home?

And in Dreamer,

The central question that kept me working on the book for seven years was,

How do we end social evil without creating new social evil?

David So we recently had the writer Ben Okri on the podcast to discuss his latest novel,

And he spoke about how art can help us face what we refuse to see.

And in his case,

He talks about the legacies of racism and oppression.

I'm curious if this resonates with your own experience,

Especially since you've written so much about the histories of injustice in the United States.

Richard Yes,

It does resonate.

My position has always been that the goal of art should be the liberation of our perception.

It should liberate us from calcified ways of seeing and even being.

There's a real Capone that I have always loved since I was a teenager and first read it,

In which a viewer is looking at a Greek statue and it's partly shattered.

It isn't completely there,

But it's beautiful.

And the last line of the poem is the viewer thinking,

I must change my life.

That's what art should do to us.

A reader,

A viewer should not come out of a work of art as clean as they went into it.

Same thing for the writer.

For me,

Every novel I write,

It's the last thing I'm ever going to do.

I'm willing to spend five years,

Six years,

Seven years on that novel if necessary as a way of trying to clarify things for myself,

And I hope for a reader as well.

Now,

Sometimes I've had assignments where I had to write about what you're talking about,

Race,

Which is not always an easy thing to write about.

There are easy ways that people think about race.

I'm more interested in the deeper ways that we can think about this particular subject.

My position has always been that race is an illusion,

But it is a lived illusion that has caused enormous damage for the longest time in human history.

When I write about race,

I'm always trying to probe deeper into whatever the subject is because it touches upon things like identity,

Personal identity,

Things that Buddhists have for 2,

600 years been wrestling with,

Talking about,

Helping us understand better.

Daishi Your novels tend to infuse stories of black life in America with Buddhist folktales and parables,

And you mentioned Oxhurting Tale,

One of your books,

And it follows an enslaved man's journey to freedom through the lens of the Ten Zen Oxhurting Pictures.

Can you say more about how you bring Buddhist themes into your work?

You said that your mentor,

Again,

John Gardner,

Initially disapproved of your interest in Buddhism,

So I'm very curious to hear about that.

Why was that,

And how did you decide to stick with Buddhism anyway because it runs through your books?

Richard Well,

John was good to work with for my first novel,

Faith and the Good Thing.

My next novel,

The Oxhurting Tale,

Not so good.

He was a shyly Christian writer.

I couldn't figure out why he was resisting this book,

Although other people resisted it too.

But he said to me,

If Buddhism is right,

Then I've lived my life wrong,

And I refuse to accept that.

What I realized at that point was that as a teacher,

He had been very good with turning me in a certain direction for craft.

But when it came to my vision,

Which was different from his,

We had to go separate ways.

That book,

Oxhurting Tale,

Was rejected as many times as Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.

Nobody understood that book in 1980.

It was published first by Indiana University Press.

That led to a review by the late culture critic Stanley Crouch.

He wrote a two-page review in The Village Voice,

And that cemented the book for readers in the sense that Grove Press picked it up and kept it out there.

And then one thing leads to another.

That book led me to do Middle Passage and receive the National Book Award.

Let's take a quick break and we'll be right back.

Are you curious about books and authors who have influenced civilizations for millennia?

Love conversation that connects rather than divides?

Continuing the Conversation is a web and podcast series that examines the mysteries of who we are as humans.

Using 3,

000 years of great books as a guide,

The series is produced by St.

John's College,

A secular liberal arts college known for great books and great dialogue,

Offering a bachelor's degree in liberal arts and master's degrees in liberal arts and Eastern classics.

Listen to Continuing the Conversation on podcast platforms and the St.

John's College website sjc.

Edu.

That's sjc.

Edu.

Now let's get back to our conversation with Charles Johnson.

So throughout all of this and through your career,

You've been meditating,

And I was wondering what the relationship is between your meditation practice and your writing.

Do you view the writing,

Say,

As a spiritual practice or as a meditative practice?

Whatever creative work I'm doing,

It is an extension of my spiritual life.

My work is informed by it,

But I have to say that after so many years of meditation,

I see everything as part of my spiritual practice,

Whether I'm engaging with my grandson or whether I'm going to the supermarket and talking to the person,

Checking out my groceries.

I try to be in that place of spiritual consciousness all the time.

Now just before we started,

I sat on my tattered and worn Zafu and had my formal sit because I would not do a session like this until I cleared my head and spirit.

The point is that when I get up off my pillow,

I want to have that same consciousness throughout the day.

It's about everything that I do that includes the creative work as well.

You always have struck me as an incredibly disciplined man in just about everything you do in the many fields you work in.

There's a real Protestant work ethic going there too.

It's pretty amazing to watch.

But I remember once I was listening to Michael Imperioli and Philip Glass and Gaelic Rimpochet on a panel,

And both Philip and Michael were saying that the very thing that made them disciplined and able to apply themselves to their work the way they did was what also allowed them to apply themselves to their practice and explore it in a similar way.

Is that true for you?

We're talking about a particular kind of discipline,

I suppose,

And it does bleed over into every aspect of our lives.

The beauty of Buddhist practice is that it allows us to bring a degree of control over our lives.

We learn how to look at our own mind and the arising and falling of thoughts and feelings,

And to be able with equanimity to examine those thoughts and feelings and not be caught up in anger,

For example.

This is very much a part of my discipline.

So as if you don't do enough,

For the past few decades you studied Sanskrit intensively.

Sarah tipped me off,

Our producer,

To a blog post you wrote for Ethelbert Miller,

And you describe it as,

Quote,

Your most serious intellectual and spiritual hobby,

A language I will study until the last day of my life.

Now that's commitment.

Can you say more about how you came to study Sanskrit and what you love about it?

Well,

When I was in my teens and I was doing my Eastern philosophy studies,

I naturally came across Sanskrit.

And I always thought,

I don't have any talent for languages.

Middle school,

High school,

All the way through college,

I think I had seven years of Spanish.

But I don't have a natural talent because I think I'm a visual person.

Some people are ear people.

They hear with subtlety.

I don't.

And that's what you need really to know three or four different languages.

But as it turned out,

One day we were working out in our martial art studio,

And on the bulletin board they had put up a little flyer.

So when we were taking a break from working out,

I looked at it and said,

Learn Sanskrit over the weekend.

It was a flyer for the American Sanskrit Institute.

And their approach is rather different from academic foreign language Sanskrit departments.

And so I went,

And it was a wonderful,

Incredible three days of immersion with my teacher,

Ajah Thomas,

Who is a priest,

Actually.

And so I've studied with Ajah for a long,

Long time.

The American Sanskrit Institute approach is holistic.

The same way it was in India and is in India.

It is my most serious intellectual hobby.

I wish I had time to get back to it because I really have to study every day to make progress.

I'm writing a piece right now,

This book,

The Philosophy and the Art of Writing,

And that's taking up all my time.

But I walk around with Sanskrit in my head all the time.

Daishibhyaan Has it in any way shaped how you write English or changed the way you write English?

Do you play with that?

David Oh,

Absolutely.

When I first started studying Sanskrit,

I would grade my students' papers,

Their stories and so forth.

My sensitivity to language was so acute in terms of rhythm and meter.

It really had a good impact on my dealing with my students' work,

But then also my own work too.

Daishibhyaan I mentioned you're a Sanskritist,

A cartoonist,

You're a martial arts teacher.

And I'm wondering what drew you to the martial arts and do you see a relationship between your martial arts practice and your writing?

David I started martial arts when I was 19 in Chicago,

Chittawachuan of the monastery.

It was like a cult,

Really.

I did a lot of karate,

And I finally settled in the early 80s into one system,

Chorley foot,

As taught by Grandmaster Doc Phi Wong in San Francisco.

I started there,

Training in his school.

Then we had schools here in Seattle,

In Bremerton,

Washington.

So,

I've been doing this for a long,

Long time.

We have a workout tonight,

As a matter of fact,

With me and some of my old friends.

I'm 70,

Another guy is 50.

We have seen some of our teachers and friends pass on over this long period of time that we've been training,

But we still get back to it.

Because one of the things you want to do in life,

If possible,

Is the integration of mind,

Body,

And spirit.

I think I said to you before in our last interview,

When I was young,

I said,

Okay,

You know,

That's what I want to do.

I want to develop myself in three directions—mind,

Body,

And spirit.

For mind,

I chose philosophy.

For body,

I chose the martial arts.

And for spirit,

I chose Buddhism.

They flow together and reinforce each other in one way or another.

I will have to say that there's certain very high kicks I don't want to do anymore.

I have to be very careful about it at age 74 or I'm going to feel it the next day.

So you make adjustments over time.

Tai Chi is very important to me right now.

Daishi You recently published a graphic novel called The Eightfold Path,

Aptly enough,

Which is an anthology of Afro-futuristic parables inspired by the Buddhist teachings.

Can you tell us a little bit about the project and how it came about?

Daishi It was a collaborative work.

I went along for the ride.

That's the way I see it.

The stories are by my friend,

Afro-futurist,

Sci-fi writer Stephen Barnes,

Who's published a lot of books.

And it's illustrated by Brian Moss,

A talented young artist.

And what Steve wanted to do was a graphic novel,

And he was inspired by the old EC horror stories.

But he didn't really have a background in Buddhism,

So he brought me on board to interject in places where I could,

Both Western philosophy,

But also as much Buddhism as I could get into his stories.

And then I wrote a final essay that's at the end of the book explaining for readers what the Eightfold Path is,

If they don't know.

Daishi We recently interviewed Bernard Foer on the podcast,

The historian of religion,

And he celebrates the multiple manifestations of the Buddha from the early texts to graphic novels to science fiction.

And he spoke about how cultures have continually reinvented the story of the Buddha,

Constructing new myths,

Developing new genres.

And it seems like this graphic novel anthology is a continuation of that tradition.

What can be gained by translating Buddhist teachings and stories into other mediums?

Bernard Foer Buddhism is 2,

600 years old,

And nothing was written down in terms of my understanding for about 500 years.

So it was oral tradition.

So there were technologies that developed over millennia for the communication of Dharma that didn't exist in the Buddha's time,

Didn't exist in the 19th century.

A new form that is very popular in this country right now is the graphic novel,

Graphic arts.

The impact graphic novels have had on popular culture,

To me,

Is amazing on movies,

On television programs.

They are the source material.

So why not for introducing readers to the Dharma?

Daishi Do you like depictions of the Buddha in manga?

Bernard Foer It's okay.

It's very influential.

I've got comics here in my garage,

And among them you're going to find manga.

I have a series that was done on the life of the Buddha in a manga form.

Yeah,

It's absolutely okay.

Daishi So Chuck,

Your retelling of an old Zen tale appears in the February issue of Tricycle.

The story is called,

Is That So?

Can you tell us about that story and what it means to you?

Bernard Foer Well,

I thank you for taking that story and publishing it.

Since my teens,

That was when I first encountered that story,

Which is only three paragraphs in a lot of the versions that I've seen.

I've simply thought about it for all of my life.

In 1998,

I fathered a reading series here in Seattle for Humanities Washington.

It used to be called the Washington Commission for the Humanities.

Every year,

They have a fundraiser in October,

And I suggest,

Why not have writers write a new story and read it,

And you give us a theme or a prompt?

Every year,

There's a different theme related to bedtime.

The one for the story you're talking about was light in the darkness.

And many people,

Writers locally have participated in the bedtime stories event.

My late friend,

The playwright,

August Wilson,

Did it three times.

My former student,

David Gunnarsson,

Author of Snow Falling on Cedars,

He's done it.

So I had to write a bedtime story.

And my thought was,

Okay,

What do I want to write about light in the darkness?

And so I reached back to that story.

I thought to myself,

Okay,

Suppose I update it.

Suppose I set it on Dashon Island.

I said,

Well,

Let's look specifically,

What would happen if you suddenly had a baby put in front of you,

And you have to take care of it?

What I thought about in terms of the details was this will become for this abbot his way,

His practice,

This baby,

Which in order to take care of a child,

You have to stop being a child yourself.

So every moment of the day,

This life is one he's responsible for.

It transforms him.

People think it's his baby.

And so his temple begins to lose parishioners and laypeople.

But he stays the course until the grandparents come and ask for the baby back,

Because their daughter had lied to them about him being the father.

So now he has to experience letting go.

First,

The process of dealing with this baby,

Which creates him as a father and a mother through love and identification with this child,

And then the child is taken away.

So he has to learn at the end of the story how to have a deeper and more fully realized broken heart.

Daishi,

As I remember the first time I read it,

It had more to do in my mind with,

This is your child,

He says,

Is that so?

He accepts it without complaint.

And then they come to take it and they said,

This isn't your child.

He said,

Is that so?

And they take it.

I thought of it in terms of praise and blame,

But in this story,

It's really about unexpected gain and then a terrible loss.

Yeah,

It's a powerful story about accepting the present moment.

Oh,

Is that so?

Okay.

But I kept thinking to myself,

What changes is this abbot going through as he takes care of this baby?

And what emotional changes?

And his life is turned upside down.

But he has learned from the experience and evolved spiritually.

But it doesn't come without pain and suffering.

Daishi,

Well,

I was abroad and I was lying in bed when your agent sent it to me.

And I thought,

Oh,

This is a novel.

And I put it aside for a moment and wrote her back and said,

I'll read this book when I get back to the United States.

She wrote back and said,

It's not a book.

So I read it really quickly and I was immediately smitten.

And I thought,

Okay,

We've got to publish this.

So thank you for that.

And for our readers,

You can read it in the February issue.

It's a wonderful retelling of an old Zen tale.

So Chuck,

Between Sanskrit study,

Martial arts,

And many,

Many publications,

It seems like you've always got an iron in the fire.

So what are you working on now?

I'm working on trying not to be working on things.

Yeah,

I'm always working on something because I'm always curious about the world and what's going on.

I don't force it.

And when there's a story to write or a drawing to do,

Then I do it.

Well,

Charles Johnson,

It's been a great pleasure for our listeners.

Be sure to check out Chuck's story in the February issue of Tricycle and his many,

Many books.

Just go online,

Google Charles Johnson,

And you'll find a very long,

I would say,

Endless list of work.

It's a pleasure to talk to you always.

So thank you,

Chuck.

Thank you.

You've been listening to Tricycle Talks with Charles Johnson.

To read his story in the February issue of Tricycle,

Visit tricycle.

Org slash magazine.

Others featured in the issue include Karen Armstrong,

Pico Iyer,

And Jacqueline Stone,

Along with teachings on how stories and myths shape our understanding of ourselves and the world.

We'd love to hear your thoughts about the podcast,

So write us at feedback at tricycle.

Org to let us know what you think.

If you enjoyed this episode,

Please consider leaving a review on Apple Podcasts.

To keep up with the show,

You can follow Tricycle Talks wherever you listen to podcasts.

Tricycle Talks is produced by As It Should Be Productions and Sarah Fleming.

I'm James Shaheen,

Editor-in-Chief of Tricycle The Buddhist Review.

Thanks for listening.

4.9 (31)

Recent Reviews

cate

January 1, 2024

Inspiring. Made me look up some of his novels.