1:00:12

1:00:12

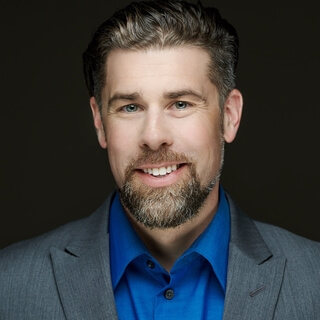

Interview With Michael Poffenberger

Rated

5

Type

talks

Activity

Meditation

Suitable for

Everyone

Plays

274

Michael Poffenberger is part of a younger generation of leaders seeking to integrate contemplative practices with compassionate social action, and serves as Executive Director of the Center for Action and Contemplation. Michael helped to found the Uganda Conflict Action Network, which is now called Resolve. At Resolve, Michael led bipartisan coalitions and developed international campaigns to advance policy change for war-affected communities in Africa.

LeadershipChristianityContemplationHuman RightsInterfaithYouthTransformationCommunityGriefChristian ContemplationSpiritual LeadershipAdvocacyInterfaith DialogueChildren EngagementCommunity BuildingGrief ProcessingInterviewsPersonal TransformationSocial ActionSpiritual PracticesSpirits

Meet your Teacher

Thomas J Bushlack

St. Louis, MO, USA