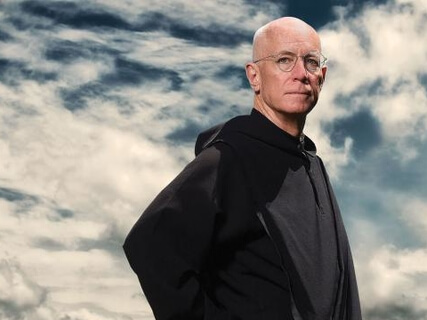

Episode 21: Interview with Fr. Columba Stewart, OSB

Fr. Columba Stewart is the executive director of the Hill Monastic Manuscript Library (HMML) at St. John’s Abbey in 2003, Columba has traveled extensively throughout the Middle East, Africa, Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and India, cultivating relationships with communities possessing manuscript collections from the early medieval to early modern periods. In this podcast, he describes both his studies of early Christian monastic contemplative prayer and his personal practice of the Jesus Prayer.

Transcript

I pick up,

I start reciting,

And my eyes fill with tears.

I'm aware that I've made access to that deeper part of me that normally is not accessed,

Because I'm dealing with the emails,

The thoughts,

The task,

The personal interaction,

The problem with somebody,

All of this.

I'm not the only one,

I'm not the only one.

Hey there everybody.

I'm your host,

Tom Bushlach,

And welcome to episode 21 of Contemplate This.

This interview is with Father Columbus Stewart.

He is a Benedictine monk at St.

John's Abbey in Collegeville,

Minnesota,

An eminent scholar of early Christian monasticism and spirituality,

And he currently serves as the director of the Hill Monastic Museum and Manuscript Library,

Or HEML for short,

At St.

John's.

The work that Columbus is doing at HEML has gotten international media attention recently,

As they have been going into war-torn areas such as Syria or Iraq,

And digitizing ancient manuscripts that groups like ISIS and others might seek to destroy.

You might not think that the work of digitizing the world's ancient religious manuscripts would be that exciting,

But it might help to picture Columbus kind of like a cross between a Benedictine monk and Indiana Jones.

This interview was also personally very rewarding for me to reconnect with Columbus.

In my early 20s,

I considered joining the monastic community at St.

John's,

And I spent the summer of 2003 as a candidate at the Abbey,

Which is kind of like a period of living in the monastery and discerning whether or not to enter the community as a novice or a first-year member.

At that time,

Father Colombo was the formation director,

And when he heard that I decided not to stay,

He invited me into his office for a very candid conversation about my decision not to stay.

It was one of those crucial,

Supportive conversations with a wise figure that took place for me right at a moment of change and transition,

And I will always remember his kindness and willingness to listen during a period that was pretty difficult for me as a young man deciding what to do with my life.

You can find this episode along with the show notes at thomasjbushlack.

Com forward slash episode 21.

That's the word episode 2-1 with no spaces.

I have some links there to his books and to his recent Jefferson lecture that he delivered to the National Endowment for the Humanities,

Which is a pretty big deal,

So you might wanna check it out.

While you're there,

You might notice a new look and feel to my site at thomasjbushlack.

Com.

Now,

First of all,

All the old content is still there,

The blog posts and the podcasts and everything,

But it's been redesigned and laid out to highlight my public speaking and professional development workshops,

And you can now access my online courses previously at Contemplative View now directly on my site.

To view those courses or guided meditations,

You can just click on the Shop dropdown menu at the top of thomasjbushlack.

Com.

And if you or your organization are looking for a speaker on contemplative practice or leadership development for an upcoming event,

You can contact me directly through the Contact tab on my site.

I also wanna let you know that in the coming months,

I'll be releasing another new site at centeringforwisdom.

Com.

This site will feature my Centering for Wisdom leadership assessment tool,

Along with other resources to help you deepen your contemplative practice while improving your decision-making skills for growth in personal and professional life.

If you wanna stay up to date with all these exciting changes,

You can subscribe to my newsletter right at the top of the main website at thomasjbushlack.

Com and as a bonus,

You'll instantly receive a free downloadable MP3 of one of my guided meditations.

Again,

You can subscribe to this wherever you get your podcasts,

Including Apple Podcasts.

Always appreciate your reviews,

Especially written reviews as they help to spread the word.

Okay,

Thanks for being here and with those announcements,

Let's get right into my interview with Father Columbus Stewart.

Welcome everybody,

I'm here with Father Columbus Stewart,

So thank you for being on Contemplate This.

Hey Tom,

Happy to be here.

Good,

Why don't you start by introducing yourself,

Maybe tell listeners a little bit about where you are in the world and then how you got there.

So I'm a Benedictine monk of St.

John's Abbey,

Collegeville,

Minnesota,

A large Benedictine community,

Very involved in educational work and publishing.

My particular job these days,

And for the last 16 or so years,

Has been as Executive Director of the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library,

Which is a project founded by our Abbey,

Now sponsored by St.

John's University,

That for more than 50 years has gone around the world photographing manuscripts that are thought to be endangered.

A Christian,

Muslim,

Just starting a project with Hindu and Buddhist material.

All the Jewish stuff's already been done by a project in Jerusalem,

So we're doing the rest of it.

What stuff?

Sorry,

I didn't catch that.

The Hebrew stuff.

Oh,

The Hebrew stuff,

Okay,

Cool.

So you're covering all the bases.

We're covering everybody else.

Yeah.

At least to the extent that we can.

Yeah.

That has me on the road a lot,

Has me meeting a lot of different communities,

But wherever I go,

I carry with me my identity and my practice as a Benedictine.

Mm-hmm.

Okay,

So do you wanna say a little bit more about how you identify those manuscripts,

Or which ones sort of make the cut?

How does that work?

So our primary criterion for what we describe as digital preservation of manuscripts is finding locations in the world where manuscript libraries,

Which could be in a religious institution,

In a private archive,

In a family,

Where they're thought to be at risk.

And there are many forms of risk.

There's the risk of conflict or war.

There's the risk of poverty,

Where people just have a difficulty maintaining these collections in a way that's needed to preserve them physically.

There's also the danger that comes from communities which are themselves at risk.

This is like the Middle East,

Where Christian communities are basically evaporating in real time now,

Leaving behind their cultural heritage.

So we like to work regionally and sort of in depth.

So we don't do just isolated collections here and there,

But we'll say,

Let's go to Iraq and do what we can.

Let's go to Southwest India and Kerala and work with St.

Thomas tradition Christian archives,

The best we can.

And we have a big project right now in West Africa in Mali with Islamic manuscripts from Timbuktu.

So it sounds sort of disconnected,

But in fact,

There are some logical connections and there's breadth and depth in each region where we work.

Yeah.

And I know some of the work that you've done has gotten like national and even international attention,

Particularly in areas that are maybe threatened by groups like ISIS,

Where they wanna go in and sort of destroy like the cultural heritage,

Right?

Which part of that is the textual tradition.

That's right.

Which speaks to something that maybe we don't think about all that much is the importance of preserving those ancient textual traditions.

So how do you think about the importance of preserving that and then digitizing it and making it available?

Well,

People sometimes ask me,

So,

Okay,

What's actually in these manuscripts?

And then my answer is to say,

Well,

Whatever they thought was worth writing down.

Yeah.

At a time when writing down costs something,

The materials were precious,

The skill to write was not a skill that everybody had.

So if we're going to have access to the way that our ancestors,

Either our sort of lineal ancestors or our ancestors in the broader sense of the whole human family,

What they actually thought about,

What they believed,

The struggles they had,

The controversies they were involved in,

The reflections on the history of their community,

The sole access we have to that is what they wrote in their manuscripts.

And if you believe that accessing that kind of information,

Those stories,

Those reflections at the value,

Which would be a fundamental conviction,

Of course,

Of anybody who believes in the humanities or the liberal arts,

Then you have to have access.

And that's where we come in.

I'm thinking about that phrase that you hear about,

You know,

If we forget our history,

Then we're just bound to repeat it over and over again,

Which gets at one piece of the importance of remembering those historical artifacts and times.

Are there any that are particularly interesting to you that you've come across that you think maybe people might not understand why that's so important,

But an aha moment where you discovered something that it's like,

Wow,

That really tells us a lot about the history of a particular culture or religious tradition that's important for today?

I'll give you an example along the lines of,

You know,

We're condemned to repeat history if we don't learn from it.

There's a manuscript in Aleppo,

Syria,

Which contains the only surviving copy in the Syriac language,

Christian Aramaic,

Basically,

Of a history of the world.

And this was written in the 12th century by a patriarch of the Syriac Orthodox Church named Michael the Great.

And the only copy of it that has survived over the centuries is actually a 16th century copy,

But there's no earlier one.

So he's writing at the time when the Crusaders were coming from Europe into the Middle East to liberate the Holy Land.

Yeah,

So Columbus doing air quotes for people who can't see around liberate.

Right,

And what they failed to really understand is that there were already Christians there.

So,

You know,

In some sense,

You might argue the original Christians,

I mean,

The people who actually come from- The ancient Syriac traditions that go as far back as we know.

So these are people who are in the same kind of linguistic and cultural milieu as Jesus and the earliest disciples.

And so when the Europeans arrived with their military might and start attacking these areas,

Which of course are ruled by Muslims at this point in the Crusades,

Islam had conquered that part of the world in the seventh century,

So we're several centuries into Muslim rule.

Guess who took the heat?

Guess who got caught between those two powers,

The invading Europeans and then the local Muslim rulers.

Of course,

It was the Christian minority.

And so this patriarch writes about the way that the Christians were punished by their Muslim rulers for the arrival of the Crusaders.

So for example,

They were forbidden from ringing their church bells.

And so what's the historical parallel?

2003,

We invade Iraq,

We deposed Saddam Hussein,

Iraq collapses into a kind of lawless state because of the lack of wisdom in terms of preparing for a new government and civil institutions.

And the result is Christians get caught between the various forces which are trying to seize control of parts of Iraq and Iraq,

Which was one of the most Christian parts of the Middle East,

A minority,

Yes,

But millions of people belonging to the Christian churches in Iraq,

Most of them leave.

So they are being persecuted,

They're being forced out of their homes because of the arrival of the Westerners,

In this case,

The Americans,

Not the Europeans,

Because they've come to bring liberation and democracy.

This benighted part of the world.

So there's a great example.

Now,

Did anybody who planned the invasion of Iraq read the world history of Syria?

I don't know if I like to pay for our credit card.

Not likely.

And I'm guessing that the Pentagon didn't call you for an update.

No,

I sat by the phone.

So I mean,

This isn't to say that the study of these texts makes a huge difference in human behavior.

I mean,

The people who led that invasion,

For example,

On our side,

Were all college educated people who had historical background.

But it does give us a little more information in terms of understanding places and peoples.

And also,

Perhaps a more nuanced framework for understanding our own experiences.

Because of course,

In the Christian tradition,

We read the Bible,

We read the great spiritual writings.

We're always drawing resources from that deep and broad tradition precisely to help us make sense of right now,

The world in which we live and the daily challenges that we face.

I'm thinking about,

There's a line that I think it's from John Paul II in one of his encyclical letters,

Where he talks about the need for like a Western European Roman Catholic,

But also all the other Western denominations that come to remember and reconnect with our Eastern brothers and sisters,

The Orthodox traditions.

And he uses this beautiful image of,

We need to learn to breathe with both lungs again,

The East and the West.

So I wonder if you have any unique insights into the Christian communities that really have an ancient history in the Far East,

In places that we might think of as,

I mean,

You mentioned where we think of as predominantly Muslim in the Middle East,

But even in the Far East,

There are these communities that go way back.

You've got the Ethiopian church in Africa.

I think I just read something in the St.

John's magazine about,

It was like in the Malabar Coast in India.

Yeah,

So what have we learned about some of those communities?

And I mean,

Like our connection to that.

So I think part of what we learned about those communities,

Ethiopia and the so-called St.

Thomas Christians and the Malabar Coast of Southwest India are good examples.

I think what we've learned is that there's more than one way to do Christianity.

We're so sort of conditioned to a very Western Roman style of Christianity.

And I mean,

Roman in the sense of,

You know,

Roman law,

Roman tradition,

Roman empire,

Not in the sense of Roman Catholic.

Yeah,

Even many of what we would think of as mainline Protestant traditions probably inherit that Roman broadly understood.

Totally,

Absolutely.

But then you go to Ethiopia and you find the truly indigenous African Christianity,

Which has a strong Jewish element because they both kept and then reconnected with Judaism in a way that was not true of Christians in other parts of the world.

Musical traditions and practices,

Which are obviously African when you hear them.

Their own liturgical language,

Of course,

Which is an ancient African language,

Ge'ez.

And it just blows your mind because there are parts of it that are so familiar and parts of it that are so strange.

But the point is they're authentic because they're rooted in that particular place and in the complex history of cultural interaction and influence,

Not least including the influence of the Portuguese who started to come in the early modern period.

And that sort of got layered onto it as well.

So you have Ethiopian paintings,

Which are interpretations of depictions of the Madonna and child that were brought by Catholic missionaries who didn't have a lot of success in converting them from one form of Christianity to another,

But who left their mark.

The Christians in Southwest India are also quite interesting because they are distinctively Indian.

So they come out of the same culture,

Of course,

As Hinduism,

Which was already there at the time of the arrival of Christians.

There is the memory of Buddhism in that part of the world as well before the arrival of Hinduism.

There is the effects of climate and trade and atmosphere,

All of which took what was obviously an early Christian mission,

Which they say is traceable to the Apostle Thomas.

Yeah.

On a particular beach in 52 AD.

You can decide if you wanna go for that or not.

But what's important to remember is that it's not as far-fetched as it sounds because we know that there were Roman military installations and trading posts on that coast in the first century because they had spices.

And spices were in demand.

And so there were ships going from the Middle East to there all the time.

So they are a Syriac tradition church because their founders came from Mesopotamia.

Wow.

So the same group we were talking about earlier with Michael the Great,

Christians of Iraq.

And they had centuries to develop a distinctive identity with intermittent contact back to the Middle East.

And then the Portuguese arrived.

And this time the Portuguese were a little more successful than they were in Ethiopia.

But they were partly successful through destruction,

Burning all of the manuscripts,

Doing new manuscripts with more theologically approved approaches to things according to Roman Catholic views of the 16th century.

And so the result is again this incredible mix of obviously Indian practices with affinities to Hinduism,

Ancient Syriac Christian tradition,

A kind of Western European overlay which then gets assimilated in its own manner.

And that's just a fascinating part of the world.

And they wrote their manuscripts often on palm leaves.

So you get these long palms like you'd have on Palm Sunday,

You know,

In a Catholic,

A Lutheran,

An Episcopal church.

And there's writing on them because that's where they write their history.

Huh.

Cool,

I think I'm gonna have my kids do that for Palm Sunday this year.

There you go.

What do you do with them the day after?

Yeah.

You can write something off.

Yeah.

You need to use ink that will last through these damp.

Midwestern areas.

They actually sort of carved them.

So they take like a steel nib and engrave it.

And then they smear ink on top.

And it would go into the inside part of the leaf and then you wipe it off.

You've got that.

Bingo.

Yeah.

Brilliant,

Wow.

It'll make a mess Tom but the kids will love it.

Well,

Actually that's a bonus for them,

Yeah.

Wow,

That is incredibly fascinating.

So one of my interests and the interest of this podcast is around spiritual contemplative practices.

So I would imagine that in those different sort of indigenous forms of early Christianity,

That they would have sort of had contact with,

Like you were mentioning,

Buddhist sources and Hindu traditions,

African indigenous practices.

So what do we know if anything about how that played out in their prayer life?

It's an interesting question and it's not an easy one to answer.

I would imagine.

There's always been a lot of interest among historians of Christianity about possible connections with India particularly.

Yeah,

I have been personally fascinated by this.

So for our contact with Buddhism.

And there are hints in Syriac tradition that there were contacts.

There is also evidence among the Manichaeans who were kind of a offshoot of Christianity which developed kind of its own identity,

Rather like Islam,

That there were contacts between their founder,

Mani and Buddhist in India.

But there's no kind of solid link.

And so rather than look for direct influence,

I prefer to approach it in a way kind of more anthropologically or sociologically.

That you have practices which seem to be universal.

Forms of meditation,

The use of bodily postures,

An emphasis on breathing and so on,

Which turn up in each of these traditions in distinctive ways.

And then obviously interpreted differently when it comes to theology,

But which are remarkably similar.

And in some case you can see an obvious derivation like in Islam you have the prayer posture we're all familiar with,

Where there's the going down on the knees and touching the forehead to the ground.

That was actually directly borrowed from Christian practice.

And you see Christians in the Middle East who still do this in church.

They don't have pews,

They like to use their bodies.

This is what they do,

Particularly in seasons like that.

I've had to do 40 of those before lunch.

It's reacted to monasteries during that.

It's like down dogs,

But not yoga.

Right,

Exactly.

You earn your plate of beans by doing that.

But in other cases,

It doesn't seem to be a direct borrowing like that,

But simply humans discovering the same kind of,

Call it universal wisdom,

Call it making access to what Christians might say is the Holy Spirit,

Which informs all things,

Whatever the particular religious tradition is.

And that's really fascinating,

Which of course leads to what we find in interreligious dialogue today,

Where often we meditate together,

Because we can't do anything with words,

Because words identify you and mark difference.

And we can't celebrate sacraments as Christians,

Who even weren't Christian,

But you can sit in silence.

And then you can speculate all you want about what's happening in the little air bubble above each head,

As the Buddhists and the Christians and the Hindus,

Whatever,

Are each doing their silent meditation.

Yeah,

Wow.

Okay,

I'm gonna throw out a question.

This is like,

I wasn't planning on going here,

But it's kind of headed in that direction.

And this is my own little wacky thought about some of these threads that might connect in ways that I don't think we're ever gonna get a direct proof about,

Like you were saying.

But I've always wondered about Pythagoras at this sort of,

What,

Sixth century?

Is that the right century for him?

Roughly in his own,

Yeah.

Yeah,

Ancient,

Early Greek philosopher who seemed to have these kind of wild travels before eventually settling down,

Possibly having connection with sort of Egyptian or Far Eastern practices and cults.

So do you have any insight into his role in any of this?

So Pythagoras is an interesting figure.

And what's interesting about Pythagoras is the many who came after him who claimed him.

Because he represented one of these kind of archetypal holy men,

If you wanna think of it that way.

Yeah,

Well I think they did.

We now just think of him as like the creator of the Pythagorean theorem in mathematics.

Yeah,

I was totally bored by him on those grounds.

Oh,

Same here,

Yeah.

Until later discovering,

Again,

The appropriation of him.

And then the practice of these Pythagorean communities,

Which from an external point of view,

Again back to sort of purely sociological view,

Can resemble a monastic community.

Yeah,

Or an ashram or something.

Exactly,

Whatever.

So an emphasis on aesthetic diet,

Certain communal practices,

Self-reflection,

This kind of thing.

Rigorous study,

Yeah.

So this would be an example,

I think,

Of this kind of archetype.

Yeah.

For many people,

From what Apanikar,

Others have talked about the monastic archetype.

This keeps turning up over and over and over in religious history.

And it may not survive in every tradition.

So in Judaism,

For example,

You've had groups like the Essenes up until the time of the destruction of the temple in the late first century of this era,

Who were leading an analogous kind of luck.

Yeah,

It's hard to survive when the Romans come and slaughter you.

Yeah,

It sort of really changed the landscape.

Yeah.

So I do,

I'm not bad about that.

Yeah,

Hmm.

Oh,

Interesting.

Yeah,

Thanks for entertaining my wild thought.

I know you've got probably more.

Oh,

Go ahead.

Check out the Manichaeans,

Tom.

You're probably gonna,

You're gonna groove on the Manichaeans.

Okay.

I think Mani was a genius.

I think he was just a little bit insane.

Yeah,

Well,

That's usually the case with mistakes.

The guy was a genius.

And it's just one example.

His was a particularly successful one.

Yeah.

It was utterly extirpated in the Byzantine Empire,

But it survived in Central Asia and into China until the 14th century.

Huh,

No,

I didn't know that.

That's just one example among many of these kinds of movements,

Which reflect some of these archetypal contemplative mystical practices.

Yeah,

Yeah,

I mean,

I've always kind of limited my approach to the Manichaeans to Augustine and his forays with him and then his,

Of course,

Vitriol that came later.

Not the best way in.

Yeah.

Yeah.

Little bit of polemic in Augustine.

Yeah.

Yeah,

Wow,

Okay.

Now I wanna switch gears a little bit.

This is fascinating.

But tell us a little bit about how you came into the monastic archetype yourself.

How'd you come to St.

John's?

So I was born in Houston,

Texas,

Grew up there.

Then I went to college on the East Coast,

Started a doctorate on the East Coast in basically religious studies,

Church history.

Just as that was happening,

Starting that graduate work,

I met a couple months from St.

John's.

I had been interested in some type of religious vocation.

I wasn't sure what.

I mean,

I was like 23 years old.

I mean,

I was exploring all kinds of options.

Was religion,

Catholicism a big part of your family growing up?

It was intermittently important.

Okay.

We,

Periods of practice around like sacramental milestones.

But we always had a strong sense that we were clearly Catholic,

And Catholic was important.

And- And in the South,

That has a different kind of resonance,

I think.

Yeah,

The sort of Louisiana,

Gulf Coast Catholic background that I come out of.

And of course you're Catholic,

Because what else would there be?

We're the kind of old religion,

Right?

So,

I mean,

We have the history,

We have the culture,

We have all these things.

And it wasn't a kind of narrow ethnic view,

But it was just part of the fabric of how you looked at things.

So anyway,

I met these couple of monks on the East Coast.

They said,

Got to know me.

One of them finally said,

Why don't you come spend the summer of St.

John,

Summer of 1980?

I had to learn enough German to pass a reading exam for my doctorate.

I had already done my French and my Greek and my Latin,

But I had to do German.

So I came out here and spent a few weeks that summer,

And it happened to be the 1500th anniversary,

The official,

Just say,

1500th anniversary,

The birth of St.

Benedict.

We don't know exactly when he was born.

And so I'm here,

College of Minnesota,

A very important Benedictine monastery,

And all these experts,

Scholars,

Truth leaders,

Are flying in for symposium and workshops.

It was like a crash course in why this is important.

And even cool.

So that was very powerful.

I decided that rather than get my doctorate and then sort out my life,

I would sort out my life and then get my doctorate.

So I quit graduate school,

Joined the monastery in early 1981,

Made my vows in 1982,

My final vow was 85.

And then I went off to Oxford to study.

And that's when I started working on early Christian asceticism,

Monasticism and mysticism.

Well,

Let's go there.

So you wanna take us through that,

Both,

I guess,

It's both a personal and a scholarly pursuit,

Right,

Of early monastic and ascetical movements,

Which I think is just endlessly fascinating.

So I got,

I mean,

Obviously I was interested in Benedictine monasticism,

But I had already studied a lot of Eastern stuff.

So I'd learned Greek,

I learned a little Syriac before I went off to Oxford to do the doctorate.

And I was starting to get interested in the real origins of monasticism.

I mean,

Like,

What is the milieu in which Christian monasticism develops as a thing?

Were there key moments,

Were there key places,

Were there key texts?

So I did research on what you might call kind of premonastic movements,

And particularly what you find in the Syriac world with its Christianity,

So much closer to a kind of,

You know,

Hebrew,

Aramaic,

Jewish frame of reference because of the linguistic and cultural affinity.

And then how that moves into Greek.

So I got very interested at that point into how a text moves from one language to another,

Or is moved from one language to another,

How they change,

How they're received,

Which ideas and which texts make that transition.

And so that's been a theme of my work ever since then,

Whether from Syriac to Greek or Greek to Latin or Greek into Syriac more recently.

So I love that kind of crossing of frontiers with certain ideas,

And then how that plays out with the kind of new host culture,

And how it changes them,

Or even in some case,

Overwrites their own history,

And they forget their own origins.

So these are the sorts of problems that I followed.

And then alongside that has been another track of looking at these writings on prayer.

So the more mystical,

Contemplative element that you're interested in here in this podcast.

And so I did some pretty intensive work looking at key early monastic figures.

Evagrius,

Who's a monk in Egypt,

Came from Asia Minor initially,

But sort of got his monastic identity in Egypt.

He wrote really interesting and sometimes difficult writings on prayer,

Spiritual knowledge,

A lot of it rooted in philosophy,

So he was very pointed in Greek philosophy.

And it was rooted in philosophy because that's what they knew.

That was their frame of reference.

That was their intellectual culture,

That's the very language they had in Greek to write about such ideas came from philosophy.

And then I got interested in how his ideas came into the West.

So there was a guy called John Cassian,

Latin writers spent some time in Egypt,

And he basically translated that mystical theology of Evagrius into Latin.

That brings it into the Latin world.

Cassian's writings are very popular,

They influence Gregory the Great,

Who of course is the,

Some say the last of the fathers or the first of the medieval theologians,

Who takes that tradition,

Connects it with Augustine's mysticism,

And gives us what is basically the Western mystical tradition.

So I sort of followed that whole line of transmission.

Evagrius is in many ways the source,

And the purist approach to this kind of distinctive understanding of contemplative prayer and experience.

So I've spent a lot of time looking at the way he wrote about what he calls prayer without images.

The idea being this kind of higher spiritual form of contemplation which moves beyond words,

Mental depictions,

All of those ways in which we both express and imprison spiritual experience.

And he got pretty out there in the ways he wrote about that,

And I thought that was really,

Really interesting.

Yeah,

So how would you characterize that if you were to continue to unpack that for somebody who maybe has never even heard of Evagrius before?

In terms of how would he,

If somebody came to him and said,

Father,

Give me a word,

Like the Desert Fathers,

Where would he start with working with somebody if they were like,

I wanna practice this wordless,

Apophatic prayer?

Well,

It may seem sort of counterintuitive,

But the way he would start them is he would say,

Memorize all the songs.

And why don't you throw in the book of Proverbs while you're at it?

Later on we can talk about the ascents,

Or we can talk about the song of songs.

Though the monastic life as these people understood it consisted of memorizing big chunks of scripture,

Reciting it prayerfully while you work,

While you walk,

While you do all these things.

They would come together and do that communally,

They would do it individually.

You would try to understand readings,

Either that you hear in church or that you're reading yourself in your cell,

And bring to bear various forms of interpretation,

Many of them again derived from philosophy,

Like allegorical interpretation and so on to understand the text.

But the fundamental practice was this internalization of the biblical word.

And so that becomes the foundation of the prayer life,

This what they would call a rumination or a meditation,

Because meditation literally of course means repetition.

Yeah.

That's where the word comes from.

So you internalize these words and songs,

You're praying them,

And they lead to moments,

They would say,

Moments where you would move beyond the words and beyond the imagery and metaphors that the words express to something which is beyond them.

And Evagrius would say,

This is the closest we get to actually kind of making contact,

Like,

You know,

Direct mind to mind contact.

With God.

With God,

Because with this platonic understanding of the human person,

Of course,

The spiritual is the real,

The ultimate,

That's where the action is.

The physical material is necessary for our life and existence in this earth.

But the part of us which is most like God is the mind,

The intellect,

The higher,

The rational faculty.

Yeah.

Let's put it that way.

And he says that when you have these experiences of wordless,

Imageless prayer,

He says,

That you have an experience of a kind of blue light.

And he says it's the immaterial light of heaven.

And possibly the immaterial light of the very holy trinity itself,

Although this is an open question,

Exactly what you're seeing.

Or maybe what you're experiencing is simply the blue light,

The heavenly light of the intellect itself,

Of that part of ourselves itself,

Fully realized,

Which then by its very nature is in analogy with the uncreated divinity.

So wow,

You know,

We have our blue light,

Beyond form and word and line.

This gets pretty out there.

But it's intriguing.

And it's also intriguing because he said,

This doesn't last.

You know,

You spend five years memorizing songs and then you spend the rest of your monastic life living the blue light.

Blue light special.

That's right.

That's right.

You're sort of rocking the blue light for the rest of your monastic life.

That these are brief experiences.

And so then somebody like Cashin gets hold of this.

And Cashin says,

This is really interesting,

But it's kind of chilly.

Yeah.

You know,

There's not much feeling there.

Yeah.

You know,

Blue light is cool light,

Right?

So it's beautiful and it may be like heaven when you look up in the sky,

But it may not speak to everybody's experience.

So Cashin takes the same concept and he talks instead about a prayer of fire.

And so you get a little warmer thing that you're praying your songs and all of a sudden your spirit is kind of caught up,

He says.

In an ecstatic moment.

He calls it an excess of the mind,

Going beyond the mind.

It's just mentis.

And he says,

You're beyond words.

The ability of words to express this kind of exuberance and exhilaration.

He said,

It feels like a jet of fire sort of flaring up and seizing the mind,

He says,

And sort of taking it off to this higher realm.

And that is without image,

That is without words.

Because again,

It's moved beyond these ways that we humans try to both articulate,

But then unwittingly imprison these spiritual realities.

And then of course you come back down to earth.

What's interesting about Cashin is he talks about the ways this can happen.

So,

You know,

You're in church,

You're praying the Psalms,

Somebody chants something,

The voice is beautiful,

Off you go.

You're saying your own recited Psalms,

And suddenly you have an experience where the word touches you deeply.

And he calls this compunction.

We think of as being sorrowful,

Because that's what compunction means for us.

I felt compunction about the fact that I had kicked my little sister.

Or I felt compunction about the fact 20 years later that I had treated somebody shabbily back when I was young.

But in Cashin's view,

Compunction could also be joyful.

It's just a way of talking about stuff really getting in,

The heart being touched,

Literally punctured.

So this,

I don't wanna cut you off,

But this sounds a little more embodied than the pure intellect that you were talking about with.

And connected to it is tears.

So Cashin's the first person to give us a Christian phenomenology of tears,

Which can be joyful,

Sorrowful,

Exhilarated.

But in his view,

And this would also be the view of the broader monastic tradition,

And Evagoras even hints at this,

But he doesn't always say it so clearly.

The true indication of spiritual experience is the presence of tears.

Because in a sense,

You kind of opened up something in the spiritual engine of the self.

And when the mind and the body and the heart are functioning as they should,

The kind of natural exhaust,

The output of that is tears.

The gift of tears,

Of course,

A promise later.

Yeah,

Yeah.

I haven't read as deeply into some of these thinkers,

But a lot of the more contemporary sort of interest in recovery of Christian contemplation has come through kind of a recovery of practices like Lectio Divina of reading scripture in a prayerful way,

In a heartful way that can lead,

Similar to what you're saying,

If you're faithful to the practice,

It's not like you're doing it so that you can guarantee a certain experience,

But with faithfulness to a regular practice,

This is what tends to happen.

We have these little moments that kind of creep in almost unexpected.

And there's an understanding,

Like Cashion,

I think,

Talks about the constant repetition from,

Is it Psalm 69?

Oh God,

Come to my assistance.

Oh Lord,

Make haste to help me.

Almost becomes like a mantra.

Yeah.

And other,

Of course,

They memorize all the Psalms so they can pull whichever ones they want.

There's a sense too in which the written word and then the spoken and recited word,

You talked before about meditation as being like repetition or memorizing,

But I think in the contemporary era,

We might think of that as memorizing all the bones in the body for a biology test so I can recite them back,

But there was something different at play in what they were talking about,

Right?

There was a sense in which the words themselves were a gift of God and a living spirit that you take into yourself and you repeat as a way to engage that spirit,

And that's what sort of opens one.

Can you speak to that distinction of praying in that way versus kind of the rational sort of,

Because a lot of the mystics talk about the rational mind gets in the way of experiencing God.

So the reason they focused on,

Let's take the Psalms as the easiest example because they're,

So obviously lend themselves to prayer.

A variety of human immersion.

So in their view,

That's all inspired.

What they mean by inspired is not that God dictates it to King David and he writes it down.

What was that God?

Did I get that right?

Let's go back to line two.

What they mean by that is that the spirit is communicating with us and interacting with us through the medium of those words.

And therefore,

If we read them only literally,

We're not getting inside them to that kind of spirit level.

And so this is why they talk about different forms of interpretation.

So the moral or ethical interpretation,

The spiritual interpretation,

The metaphorical interpretation these are all ways of creating points of access to that kind of spirit that's within the skin of the words.

So that's why the Bible is uniquely valuable for this kind of access to deeper realities in a way that just making up some nice little phrase to live by of your own could be helpful.

You put on your mirror and use it as your screen saver.

But in their mind,

It wouldn't have the same power.

Right.

Because it hasn't been recognized and received by the church as being spirit bearing.

Yeah.

The same way as these texts which have been read aloud and reflected upon and prayed over and preached about that they are recognized as having this particular call.

So this is why in their mind,

When you come to a mantra,

It needs to have that element of the kind of sacramental aspect of a biblical text.

So where this goes in the Byzantine tradition,

This comes a little closer to my own practice is the Jesus prayer.

Yeah,

I was thinking about that.

Okay.

Because you get the classic Jesus prayer,

Lord Jesus Christ,

Son of God,

At mercy I'm a sinner.

And it's actually consists of various little bits taken from the Gospels,

Which are sort of amalgamated into that particular prayer.

So it's all biblical.

It's just been kind of pieced together in the way that the liturgy often works with scripture to create a thing which isn't an actual direct quotation,

But it kind of hybridizes or different aspects.

So when you read the Eucharistic prayers,

They're full of biblical references.

So the Jesus prayer is an example of that.

And it's a kind of expanded form of the simple Lord have mercy,

Kere Elazon,

Which was often the prayer of the Desert Fathers and Mothers,

Is of course the plea of the people Jesus meets in the Gospels who need healing,

Lord have mercy.

And then you have the story of the tax collector in the temple sitting in the back with his head bowed,

Who claims his identity as a sinner.

Jesus' prayer puts all that together into a prayer that's exactly the right length,

Has biblical content,

And lends itself to a meditative repetition.

So this is the classic prayer of the Byzantine tradition,

And then with analogs found in other traditions.

And of course there's been a great rise of interest in the Jesus prayer in the West as well,

Because it just works so darn well.

And typically in Byzantine practice,

And those of us in the West who use it,

You sort of have a kind of woollen or woven kind of rosary that just consists of knots.

And it's not that you gotta do X number of them,

All that can be helpful just to have a way to know I did a whole loop,

Okay,

I'm just about done.

I gotta do two loops.

It's really just a way to have something tactile,

Like the rosary that we're familiar with in Catholic practice,

Which gives you a physical,

Tangible thing to help you focus the prayer.

Yeah.

And remember what you're doing.

The difference between the Jesus prayer rosary and then the one we know in the Western Catholic tradition is that it's all the Jesus prayer.

You don't have to remember the Creed,

The Hail Marys,

The Our Father,

These different things.

It's just all the same prayer.

And in the classic writers on this subject,

In the Greek Christian tradition,

There's an emphasis also on breathing.

Yeah.

So some sort of link between the way you pray the prayer and the natural rhythm of breathing.

So this is an obvious parallel with various kinds of Asian meditation practices.

And then this creates,

Theoretically,

The same kind of space or room that the praying of the Psalms did in Cassian's writings,

Or Agrios,

In which you can both go in and move out,

Depending on what the particular work of the spirit is at that moment.

That's the framework.

Yeah,

And I love how the connection to breath,

To repetition,

To the physical use of a bead or a prayer,

I don't know what you would call it.

If you don't call it a rosary,

Is there another word for it that they would use?

Well,

The Greeks call it a kamvaskini.

Okay.

Which is based on the knotting.

The Russians call it a chotkhi,

Which is different from chotkhis.

Yeah,

I hope so.

A chotkhi,

T-C-H-O-T.

Okay.

A lot of people just call it a prayer rope.

Yeah,

But it provides an anchor to the moment and the wandering mind to come back that creates that space in which the spirit can work,

Where we sort of relax our ego and that running commentary in the mind to allow something else to be present and work in and through us.

You silence the phone,

You set a timer or decide you're gonna do two rounds or whatever it is of the rope,

And they come in 50 or 100 knots.

And you click through them pretty quickly.

Yeah.

You can do like 115 in 10 minutes if you go my pace.

A lot of Greeks go faster.

Yeah.

They like a more urgent pace.

I like a much more meditative pace with the breath happening a couple times in the course of the prayer itself.

Yeah.

And it's a lifesaver for me.

Ideally,

When I'm at home,

I do it using one of those little kneel or prayer benches.

Mm-hmm.

I find that posture where I'm on my knees,

Although supported.

Yeah.

To be very comfortable and also focusing.

Sitting upright on a firm chair is another way to do it.

If you do it in a recliner,

You fall asleep.

Yeah.

You gotta have a little way of being attentive.

Yeah.

This thing's a lifesaver for me.

Yeah,

Can you say more about that?

And how has it been a lifesaver for you?

I live in words constantly.

Words,

Words,

Words,

Words.

Concepts,

Concepts,

Concepts.

Like everybody today,

I'm inundated with imagery,

But it's mostly words and thoughts because that's the work that I do.

I mean,

I'm dealing with texts.

I get 200 emails a day.

Blah,

Blah,

Blah.

So this is anti that because you've got just this little thing that you're focusing on.

And for whatever reason,

And I think this is a grace,

I pick up,

I start reciting,

And my eyes fill with tears.

They're not like pouring down my cheeks,

But it's like I'm aware that I've made access to that deeper part of me that normally is not accessed because I'm dealing with the emails,

The thoughts,

The task,

The personal interaction,

The problem with somebody,

All of this.

Now,

I wish I could be in touch with that part of me all the time.

Yeah.

Maybe I couldn't bear it.

Maybe it's just too much being so exposed.

Yeah,

Hmm,

We lost you.

Oh,

You're back.

Okay,

You froze with the weirdest look on your face.

Well,

So did you.

You were like.

I was in full-time mode,

And you just looked like.

Okay,

Well,

That was terrible timing on our computer's part because you were,

I think.

What did we lose?

Well,

You were talking about the grace of the tears that can come,

And then also,

Oh,

You were talking about whether or not,

What I think a lot of people experience is once you taste that,

That moment where the commentary in the rational mind sort of falls away,

It's so present and so sweet compared to the tension and stress of daily life that we just wanna stay there.

But then you were saying maybe you wouldn't be able to handle it if we did,

And I think that's right where you cut out.

Okay.

So I really need that opportunity daily to access that,

That whatever it is,

And you can say it's going inside.

You can say it's going to some higher realm.

The spiritual tradition has every possible way of describing this.

I like the sort of interior way of thinking about it,

That I'm accessing levels of experience and consciousness that are not normally engaged throughout the day.

And you know,

Augustine's great spiritual insight was that instead of spending his whole life looking for God outside,

He just had to turn around and look into himself,

And that's where we define the immaterial divinity.

And so I think that's critically important for reconnecting with myself as not only a fully human person but also as a spiritual person.

And you can say reconnecting with that grace I was given at baptism,

Reconnecting with that spirit that's flowing through us at all times.

You know,

As Paul writes in Romans 7.

But I think it's pretty critical.

Now the question is,

You were suggesting people have that experience,

They want to stay there.

Can we stay there?

Right.

T.

S.

Eliot said humankind cannot bear too much reality.

And what did he mean by that?

Well,

Whether he meant this or not,

Maybe it's saying that we can't bear to stay in this place now.

And Cassian has a really interesting way of talking about this.

Because he says,

You know,

The Lord takes us up on the mountain of the configuration.

And there we see him beyond form or image.

We have this experience of light.

He says,

But then we go back down the mountain with him,

Into the villages where we meet the people who need healing and care.

And when Cassian writes about Martha and Mary,

Rather than saying it's a contrast between the active and contemplative life now,

He says,

Here we are all Martha.

We are caring for each other,

We're fulfilling the apostolic precept of love.

Someday we will be like Mary,

After this life,

Where we can simply sit at his feet and fully contemplate.

But that's not now,

Except for these little tastes,

These little hints,

Which of course make the rest of it bearable.

Yeah,

What other sort of,

Not the right word is,

Applications,

Implications,

Do you see when you do go back to the words in the email and the work,

The daily labor,

How has that changed when you're sort of doing your practice regularly and open for when those moments drop in?

I think it makes it easier to let it go,

Easier to step back from it.

Vagrius,

In addition to his teaching on this sort of highly esoteric sounding form of prayer,

Also wrote an acute analysis of the way human beings function in his teaching on the eight thoughts,

Which we call the seven deadly sins.

And I think the value of having a spiritual practice which gives you just a little bit of perspective is it might give you a little extra ability to step back from the moment where we can so easily react or grab in that sort of reaction of anger or that compulsion of desire to say,

What's this about?

Why am I feeling in this moment the need to lash out or the need to gratify?

Now,

It doesn't mean we're gonna stop doing it.

It certainly doesn't mean that I've stopped doing either of those things,

All of their manifold forms.

But I think we've got a chance of understanding our experience a little bit better.

If there is some moment in the day,

Some part of our lives where we see the larger whole.

And I would say that another thing that helps me with this and I think speaks to many people who might not think of themselves as religious or spiritual and these kinds of ways we've been talking about is nature.

Yeah.

And there's something about the utter vastness and objectivity of the natural world that I find somehow very consoling.

I mean,

I can't manipulate it.

4.8 (17)

Recent Reviews

Odalys

September 24, 2022

Great!!!! 🙏🏾❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️🙏✝️🛐🕯🙏🏻👼🏽👼👼🏻🪷