38:41

38:41

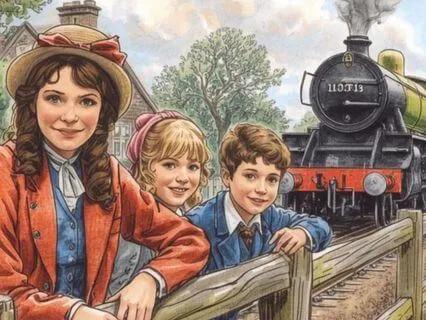

The Railway Children Chapter 11: Bedtime Story

by Sally Clough

Rated

4.9

Type

talks

Activity

Meditation

Suitable for

Everyone

Plays

1.3k

Hello beautiful souls, This is my reading of The Railway Children by Edith Nesbit, a beautiful story about three children who move from London to the countryside and fall in love with the railway. They face lots of trials and tribulations but have many exciting adventures along the way. This is a heart-warming story of love and resilience. This was one of my most cherished stories as a child. You can find all the chapters on my profile in the playlist section. I hope you enjoy this reading of a wonderful classic. Take care, beloveds.

FamilyEmotional ResilienceChildhoodRelationshipsInnocencePerseveranceJusticeEmotional TurmoilFamily DynamicsChildhood AdventureSupportive RelationshipsInnocence And NaivetyJustice And InjusticeMysteriesParent Child Relationships

Meet your Teacher

Sally Clough

Nottingham, England, United Kingdom