1:18:52

1:18:52

138 Semantic Consciousness: Abstraction Intelligence (Pt1)

Type

talks

Activity

Meditation

Suitable for

Everyone

Plays

58

"Semantic Consciousness" is the layer of our perception responsible for rationality, intelligence, and symbology (meaning-making). This episode covers how language creates reality and can skew perception. This is a Circuit 3 of Leary's Circuits of Consciousness model, continuing from the Dog Brain (circuit 2) episode.

ConsciousnessAbstractionRationalityPerceptionIdentityEmotionsPropagandaPoliticsIntelligenceSymbologySemantic ConsciousnessLanguage Creates RealityAbstractSemantic DisturbanceRole ClarityEnglish PrimeIdeologiesEmotions Territorial ConsciousnessLanguages

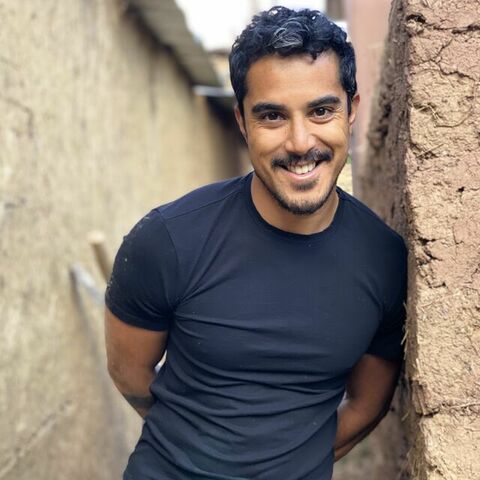

Meet your Teacher

Ruwan Meepagala

New York, NY, USA