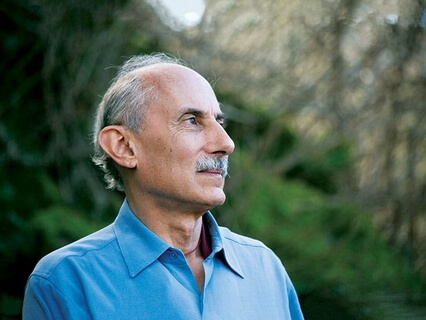

Wisdom For Our Times - Jack Kornfield

Wendy Hasenkamp speaks with Jack Kornfield and their conversation covers a wide range of topics, including how he’s interpreting our current moment, and what’s needed most; his path into Buddhism & psychology, reflecting on family and coming of age in the 1960s; links between Buddhism and psychology in terms of healing and self; the role of Buddhist ideas in activism and social justice work; the most important thing researchers can measure as an outcome of meditation practice; and more.

Transcript

These meditations invite us then to not only turn toward what's difficult that we're carrying,

But teach us how to allow them to open and be held in the great field of compassion and understanding.

And then it allows us to do our work,

To love one another,

To engage in the world,

But in a much different and freer way.

And in the stillness,

There comes knowing and intuition and connecting with deeper wisdom that we all have when we listen.

So meditation isn't just about quieting yourself,

But it's quieting yourself so you connect to something deeper,

To the source of life and to the inherent wisdom and love that's who you really are.

Hi folks,

This is Mind & Life and I'm Wendy Hasenkamp.

We're dropping back into your feed today because as we wind down on what's been an incredibly tumultuous and challenging year,

We wanted to share a special and uplifting conversation.

In September,

I had the pleasure of speaking with renowned Buddhist teacher,

Author and psychologist Jack Kornfield.

And the wisdom he shares in our conversation is so rich and timely,

We didn't want to wait to pass it along.

So in this episode,

We cover a wide range of topics,

Including how Jack is interpreting our current moment and what he feels is needed most,

Some connections between Buddhism and Western psychology in terms of healing,

And the problem of spiritual bypassing.

We also discuss how to work with mental and emotional difficulties by using a stance of allowing and gratitude.

The role of Buddhist ideas in activism and social justice work,

And Jack shares what he thinks is the most important thing we should be studying as an outcome of meditation.

The Mind & Life Institute will also be featuring Jack in January in conversation with Rhonda McGee in our new Inspiring Minds series.

If you haven't checked it out yet,

These are monthly live online conversations between contemplative researchers,

Practitioners and artists digging into some of the core issues we're facing in today's world.

You can find out more and register for free at mindandlife.

Org.

I'm really looking forward to the next one actually on December 16th,

Which will be all about embodied wisdom.

Here on the Mind & Life podcast team,

We are hard at work on season two,

And we're really looking forward to starting up again in January.

Until then,

Wishing you a wonderful holiday season,

And I very much hope you enjoy this conversation with Jack Kornfield.

We'll see you next month.

Well,

I'm here with Jack Kornfield.

Thank you so much for joining us,

Jack.

My pleasure.

So I guess I'll start with probably the question that everybody is asking you these days,

Which is kind of about our current moment in the world and in America.

Just to give some context for the listeners,

We were actually supposed to record this interview back in March.

And so then when COVID and the lockdowns all came,

We delayed this.

So it's wonderful to finally be able to catch up with you.

So we're about six months into the global pandemic of COVID.

And here in the States,

We've also been in a few months of kind of a reawakening,

Just for many a new awakening to systemic racism and protests happening daily.

And then,

Of course,

Where you are in California,

There have been horrible fires for weeks now.

It's kind of just more evidence of the threat of climate change.

So it feels like somewhat of a dire time,

But also potentially a time of great transformation.

So I'm just wondering how you're seeing this and interpreting this moment and what you think from your perspective is needed most right now.

Well,

We are in multiple crises,

As you point out,

And they're not easy ones.

They're affecting the bodies and hearts and spirits of millions,

Actually hundreds of millions of people.

Climate change,

Lord knows the scourge of racism,

The pandemic in a global way,

All of these things.

And then the fires and things which in part are a reflection of global warming and the economic injustice,

All of these kind of things together.

So I guess the first thing I would remind those who are listening is that we've been through these things before,

That as human beings,

We're survivors.

And we've been through earthquakes and typhoons and tornadoes and tsunamis and pandemics.

And we know how to do this.

We're survivors as a species and we're tremendously creative.

If we were to say,

You know,

What is true about humans besides some badly behaved things is our immense creativity.

So we know how to do this and how to get through and maybe even to use it to our benefit in the long term.

What's needed first is clear eyes and a steady heart.

When Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh talked about the crowded Vietnamese refugee boats,

He said,

When they met with storms or pirates,

If everyone panicked,

All would be lost.

But if even one person on the boat remained steady and calm,

It showed the way for everyone to survive.

So this is really an invitation and a reminder to you who are listening that you become that person on the boat for your family and your community.

And it's a kind of faith or trust that we have gone through hard things before that this is part of having a human incarnation.

From the Buddhist teachings,

The very first noble truth is that there will be suffering in life and no one who's listening can deny that in their own life.

But it's also not the end of the story.

There are causes for suffering,

Individually and collectively,

The causes being greed and hatred and fear and ignorance,

Those kinds of things that individually cause us tremendous suffering,

The ways that we cling and grasp and hate and so forth.

But they're equally the source of our collective human suffering.

Life has ups and downs and it's pleasure and pain.

This isn't about that.

This is about the potential of the human heart to go through difficulties,

Which we will all have to do periodically,

With the opposite of those,

Which are wisdom,

Generosity,

Love,

Clarity.

And the beautiful thing is that there are practices and trainings to remind us and to awaken us to this possibility.

So yes,

It's a tough time and we and people we love and just people that we learn about are going to be going through this.

It's our time when people hate to stand up for love,

When people are ignorant to stand up for clarity and truth,

When people are hoarding to stand up for generosity and care.

And the truth is that every hour on this globe,

There are a billion or seven billion acts or ten of kindness and generosity of a father putting scrambled eggs on the table for his children at breakfast,

You know,

And a mother tending to the family and people in business who are actually caring for those who come to work with us,

The people who stop the red lights so somebody else can safely go through the green.

The people who wait in line with some slight degree of patience so that the world can work orderly again and again in a billion ways.

We collaborate because it's who we are.

We're actually family.

And even though you feel the divisiveness and the ignorance or hate and they're there,

They need to be seen clearly.

They're not the end of the story.

They're the cause of suffering.

And the teachings and the wisdom that's been passed down is that we can take a different path,

The path of compassion,

The path of interdependence,

Of seeing our connection.

And this makes me hopeful.

And I'm also really hopeful for the younger generation.

They are terrified,

Like,

Oh my God,

What are these so-called grownups with little air quotes around them?

What a mess these blank blank have left for us.

You know,

We got to get on this.

But I have tremendous faith in the spirit.

You know,

There's the Greta Thunbergs of the world,

But there's hundreds of millions of them in standing up politically and musically and academically.

And there's a whole generation that's going to meet these challenges and first say,

Oeve or whatever the Sanskrit word is for that,

Dukkha,

And then say,

Okay,

We're going to do something.

I sort of went all over the map with that question.

That's great.

You mentioned practices that we can do to help us through these times.

There's of course so many different kinds of meditation.

Are there particular styles that you find have been helpful for people?

Well,

This is a podcast for Mind and Life,

Which I really love and respect as a board member and a supporter for many,

Many years.

And one of the things that Mind and Life has done in the last few decades is to foster an entirely new scientific field of inner life,

Of contemplation,

Also compassion and empathy.

And out of these now eight or 10,

000 papers and published studies that have grown in these last 30 years,

Much of it due to the spreading work of the best people,

Mind and Life,

We've seen a reaffirmation of the traditional practices,

Buddhist,

But really spread across the world.

There are beautiful practices in the ancient African and in Ubuntu and in the Mayan and Latin cultures and indigenous traditions and the mystical traditions of the Sufis and the Christians and the Jewish tradition,

All of that.

The central practices that Mind and Life has fostered in study have been those of mindfulness or mindful loving awareness,

Which is what I like to call it,

Of compassion and loving kindness and so forth.

And these are the essence of the trainings that one finds in the heritage of Buddhist psychology.

But they have their counterparts in these many other cultures.

For anyone who's interested,

There are beautiful practices on my website on using mindfulness and compassion to steady the heart,

To steady the body,

To quiet the mind,

To open ourselves,

To be able to stay clear in the midst of uncertainty,

Which we're experiencing,

To tend the body so that we don't carry so much tension,

To let it be held in a wiser way.

So the practices of mindfulness,

Mindful loving awareness,

And then the deep heart practices of compassion that connect us of self-compassion to ourselves as we go through difficulty,

To those around us,

And then more extensively to the community and the beings of this earth.

And those are the most important practices that I know,

While there are many,

Many other fine practices.

There's a great deal of them online.

You can find the best teachers all available for free.

So look for them.

Yeah.

Yeah,

It's wonderful.

And it's definitely linked to a lot of your researches,

Of course,

On the show notes for this episode.

I'd love to,

I guess,

Hear a little bit about your path in terms of your motivations to originally study Buddhism and then psychology.

My original motivations,

Like all X,

Were mixed.

I was studying pre-med at Dartmouth,

And then I took this class from an astonishingly wonderful professor who had come up from Harvard named Dr.

Wing Siet Chan and heard him talk about Taoism and Buddhism.

Sometimes he'd sit cross-legged on the desk.

And when he talked about the Buddhist teachings that there is suffering in life,

It has causes and it has an end,

That there's a vision of what a wise society or wise human being is like.

And then there are ways to do this.

I got really interested because my family upbringing was brilliant and painful.

My father was a really creative,

Innovative scientist who was also mentally disturbed.

He was paranoid.

He was violent.

He was a wife batterer.

He was always uncertain whether there'd be an outburst of rage.

So my brothers and I,

The four of us,

And my mom,

We lived with this and it was very painful and frightening.

So I heard about suffering and that there's an end,

And I began to read it.

And then I thought,

Well,

Are there old masters?

Are these,

You know,

You read about these great Zen masters and Tibetan teachers.

Does that still exist?

Could I find somebody who teaches me?

So I asked the Peace Corps to send me to a Buddhist country because I've been reading and studying and it didn't hurt that I went to Haida Ashbury in the Summer of Love and dropped acid and became happy.

And the truth is that for my generation,

Most of the most well-known Buddhist and Hindu teachers from,

You know,

Ram Dass to Sharon Salzberg and Joseph Goldstein and all the people,

Probably Pema Chodron,

We all were children of the sixties.

And yes,

We did inhale and yes,

We tried all these things.

And what happened with it is that we saw,

Wow,

The constructs of culture of how you're just supposed to go through school and get your degree and get a good job and a family and that that's what life is about.

And it,

You know,

It includes those things.

We're so limiting and that the mind creates everything and that there's these amazing possibilities of wisdom and interconnection and creativity and boundless compassion and all of that.

Okay,

How do I find this and sustain it?

So I became a monk and I trained with some of the most celebrated teachers in Thailand and Burma and India.

And after some years came back and as a lay person,

I didn't want to spend a life as a monk.

I wanted to have a family and relationship to see if I could somehow embody the things that I'd learned in a regular Western lay life.

I went back to graduate school because that's what I've been trained to do,

Be a student and get a PhD in clinical psychology.

And I also kind of wanted to figure out what happened to me.

And like,

Okay,

What did I learn?

How does this fit with our culture?

Now it happened in that first year that I was back,

So this would have been sometime in 1973,

I think,

Or late 72,

73,

That as I was starting to do my graduate studies,

I went to a meeting of the Massachusetts Psychological Association thinking that I was becoming a young professional again,

You know,

How we are as young fools as opposed to the old ones.

And at that meeting,

There was a guy from Harvard who had projected onto the screen the image of the wheel of birth and death,

The tanka that comes from the Tibetan paintings.

And he was explaining that it wasn't a shamanic talisman,

But that it was actually a diagram of the causes of human trouble and suffering in the middle.

You see greed,

Hatred,

And delusion of the opposites,

And then the different realms of consciousness that we can go into,

The realm of fear,

The animal realm where we're afraid somebody's going to eat us,

Or the addictive realm of the hungry ghosts,

You know,

Or the realms of pleasure or pain and so forth.

And then how you move from one state of consciousness to other individually and collectively.

This was Dan Goldman.

He was a graduate student there and also one of the key members in the founding of Mind and Life.

And Danny,

Who I got to meet,

I told him I'd just come from the training I had in the Buddhist monastery.

He said,

Oh,

Come over and,

You know,

Meet some other friends.

So I went to the house where Danny was living,

I think,

Actually this huge extended house of many people,

Almost like a commune,

Of David and Mary McClelland.

David was a motivational psychologist who was the chair of the Harvard Department of Social Psychology.

He's the one who had hired Ram Dass and Tim Leary and Richard Alpert and then fired them later for the LSD things they were doing.

And Danny was in his department as a graduate student and Richie Davidson was an undergraduate.

So I met all those people and then they would have soirees in the living room and there would be the Lama Chogayam Trungpa or there would be Krishnamurti or there would be Ram Dass.

And at one point,

Chogayam Trungpa,

With a drink in his hand,

Which was his usual M.

O.

,

Said we're thinking of starting a Buddhist university,

The first Buddhist university in the West,

Naropa.

And I talked about my training.

I was working on a book of the meditation practices of a dozen of the most famous masters in Thailand and Burma so that people could understand the variations in training and showed it to him.

He said,

Great,

We need someone to represent Theravada and the Southeast Asian tradition.

Will you be on our faculty?

So that started me in a summer with Ram Dass and Sharon Salzberg and Joseph Coldstein teaching.

And that was a summer where we had 2000 people under the stars in the mountains on the edge of the Rockies.

And on one night,

Chogayam Trungpa would give serious lectures about Buddhism and how you have to face the suffering of the world and be straight up about things and,

You know,

Sit up there wearing a tie and drinking a lot of sake.

And then on alternate nights,

Baba Ram Dass,

Who in those days was still,

You know,

White robes and wearing a beard and,

You know,

Bells and whistles and beads would be chanting to the gods and we'd be dancing and he'd be talking about love and everybody was loving each other.

And then Chogayam Trungpa would say,

No,

This is serious.

And then Ram Dass would say,

No,

We have to love each other.

And the 2000 people were part of this big circus of awakening that was a kind of windstock event,

If you will,

For part of this movement that now has spread so widely.

And mostly it's spread widely because we're in a culture that needs spirituality that's not just about belief,

The old religious beliefs,

But that people in this generation are really searching for ways to live wisely,

To deepen their own understanding and compassion and love no matter what tradition you come from.

And that combined with all the science research that Mind and Life has fostered,

People begin to realize,

Oh,

In education we can teach our kids social and emotional learning and they're happier and healthier.

What do you want for kids but that they be happy and they're more successful or we can use it in business or we can use it in athletics.

And then you see the Seattle Seahawks when they're getting their Super Bowl rings or the Chicago Bulls and the LA Lakers when they win the top teams and people like the mindfulness coach George Mumford who work with all these athletes who are using these trainings to help them understand how they could live and fulfill themselves.

And so it's not just about ambition and fulfillment,

But it's really about a deeper sense of love and fulfillment.

And the culture has been longing for that.

And so now it's spreading widely.

So that's a long answer to where I started and how the movement somehow grew out of it.

Right.

Yeah,

It sounds like an amazing time back,

Especially in Cambridge.

When I spoke with Richie Davidson,

He was talking about those same evenings in the living room and learning to practice with all of you folks.

So was that all happening?

You said you were in graduate school for psychology and then did you develop a clinical practice?

Yeah,

I started to do both.

Sharon Naropa,

Sharon Salzburg,

Joseph Coltsine and I,

People were inspired by the practices and teachings that we offered.

And they say,

Could you lead retreats?

Could you offer us the kind of training that you had?

And so we began to rent Boy Scout camps and facilities out in the country.

The first retreat that Joseph and I taught on the East Coast had Ram Dass and Danny Goldman and Mark Epstein and John Cabot's in came,

Trudy Goodman.

They were all students in that retreat together.

So there was this whole posse of us.

And then after a year or so,

People said,

You know,

We need centers.

We need a place that this can happen ongoing.

So we had the support of friends and were able to buy an old Catholic monastery that the church didn't need and couldn't afford.

And they more or less gave it away to us because they couldn't afford to pay the heating bill for this empty place that had a hundred rooms and 80 acres and is swimming pool and tennis court.

So we got it for one hundred fifty thousand dollars.

And gradually,

Without our doing it,

As Sharon likes to say,

We did it all without adult supervision.

Basically,

We were in our 20s that so many people became deeply interested and moved and changed.

There's something about going on a retreat if you've never done it,

Where you take a week or 10 days and step out of your life.

And every wise culture knows this,

That there's time to go into the mountains or the desert to go be by yourself and step out of your roles and your work and your family obligations and listen to your heart and listen to your place in the natural world.

And in doing so,

To find a deeper connection to your own heart and life and to the world around you.

So when you go on a retreat,

You get to do that and you get the support of other people.

You get some instruction on how to be attentive to your body,

To the emotions that come to all the thoughts that stream through and to learn how to be present for your life,

But also that you're bigger than the usual stories that you tell or the sweep of emotions that come and go.

That who you are is much bigger than that.

You are actually the consciousness that was born into this body,

The loving awareness itself.

And then you learn how to navigate it with a greater sense of freedom and joy and compassion.

And you bring back what you've learned,

The connections to yourself,

The natural world,

To all those things that are so deep in you,

Then you bring them back into your life.

Something I've always been interested in,

These complementary approaches of Buddhist practice and Western psychology in terms of healing and trauma or just any difficulties.

I'd be interested in your perspective having trained so much in both about the similarities and differences of those approaches and maybe even the idea of self,

Because it feels to me like they take a little bit of a different view on what the self is and how to work with it.

So have you thought much about that intersection?

Well I'm not sure that the view is as different as you think.

First of all,

People want to make differences and distinctions and there's value in it,

But those distinctions are also limited.

So there are things in Buddhist psychology,

And the Buddha was not,

He didn't teach a religion.

He taught a science of mind.

If you read all the original dialogues in text,

He doesn't say,

You know,

Become a religious person and just believe.

He says try these things out.

Over and over again,

He says see for yourself and here are the practices and the ways of living,

The ethical ways and the contemplative ways and right speech and right action,

Right livelihood,

How we treat one another with mindfulness and care,

You know,

How we live with one another,

And then how we live with ourselves.

So it's not about a religion,

It's really a science of mind.

And of course Western psychology faces,

Especially clinical psychology,

But also studies is what is the nature of the mind as Buddhist psychology looks at,

And then what's a healthy mind?

How do we foster that?

And there are this huge rich range of contemplative practices and trainings in Buddhist psychology that we're just now beginning to draw on in the West.

And we borrowed a lot.

There's positive psychology,

All that whole movement really drew on Buddhist psychology.

The modern neuroscience movement draws on Buddhist psychology.

The whole movement of incorporating mindful attention or even how to work with thoughts and so forth,

Much of it drawn from Eastern psychology.

At the same time,

In the Western psychological tradition,

Especially for us here in the West culturally in the USA and Europe and so forth,

There's a really good understanding of our Western conditioning,

Our tendency towards self-judgment,

Our excess of ambition and competitiveness that's unhealthy for us,

How we deal with trauma,

Our issues around addiction.

And there's so many things that I learned as a clinical psychologist that were a compliment.

They were really using the very same principles of mindfulness and compassion,

Of learning how to discern where we're caught and attached,

To see those limited identities and to step out of them,

The identity of a story or emotion we're caught in.

Now it turns out that for the wisest therapists and the wisest meditation masters,

Those distinctions fall away.

So my teacher Ajahn Chah,

You know,

Would sit on this little bench out under the mango trees near the hut in the forest monastery where we lived.

And people would come and they would ask him questions about their meditation.

What do I do when light comes or my body starts to hurt or I dissolve into some rapture state or when all this fear arises and he would guide them.

But they'd come with their practical problems.

My son became an addict to opium or my house burned down or I've been drafted to go into the army or my wife is sick with cancer.

Or we're in conflict in our village or,

You know,

I've got terrible nightmares.

And he never said,

Well,

Okay,

Those are psychological problems.

You need a therapist.

You know,

Buddhism only focuses on this and those are the wrong thing.

He had this huge bag of medicine called the great medicine of the Dharma.

And he had practices for people who were grieving and who had experienced loss that date back to the time of the Buddha.

He had practices for people who were dealing with overpowering emotions.

He had practices for people who were in conflict with one another.

And all of these were part of the medicine of the Dharma that he could offer to people.

And it was beautiful.

Similarly,

If you go to Western psychotherapy,

Especially Western clinical practice,

It's divided.

Here's the cognitive people who work with your thought structures.

And here's the trauma experts,

You know,

How you hold trauma in your body and the stories and how you release it.

And here,

You know,

The analysts who want to look at all the deep roots of your conditioning and so forth.

But if you go to the wisest therapists,

They employ the very same basic tools of mindful loving attention to you and helping in a paired relationship,

Helping you to pay attention to yourself and to the beliefs and thought structures and what are the emotions that overcome you and how do you actually hold them?

How do you step out of the issues and problems?

How do you allow the trauma to be re-experienced in a way that doesn't re-traumatize,

But held with some graciousness and compassion?

And then you start to see that they're not as different as you would think.

And part of my own life and the work I've done is really to bring together this compliment.

So in the beginning,

I got a lot of flack.

People would say,

Oh,

Therapy is low class and Dharma sitting on the zafu and getting your Zen instruction or your Tibetan Lama,

It'll solve everything.

But then you look at those Lamas and mamas and,

You know,

Swamis and whatever.

And some of them are great and a bunch of them had a bunch of problems.

And now I could tell you the names of the therapists of a lot of the great teachers that we know because they realized they actually needed help dealing with stuff and that the tradition had also allowed them to do a spiritual bypass on certain things or not deal with things so well.

And it turns out that I'm an all of the above kind of person,

That there's a tremendous compliment between the individual work we might do,

Drama work and therapeutic work and the deep meditation and that they're not opposites.

There are different ways of doing it in pairs with another person that's wise or doing it in yourself.

Yeah.

Can you just mentioned the concept of spiritual bypass?

Can you unpack that a little bit more?

Sure.

Well,

We're Americans.

We know how to misuse anything.

Right.

And you can use meditation,

But you often misuse it or spirituality.

And the misuse is to say,

Oh,

Politics isn't spiritual,

You know,

Or even the body sexuality isn't spiritual.

We should be celibate or,

You know,

The problems that I went through,

The conflicts that I had and so forth.

That's not really spiritual.

I should just think about being one with everything and practice love.

It's a great thing to do.

And the fact that my family is furious at me because,

You know,

I misuse the family money and,

You know,

I didn't respond and I wasn't there when my aunt was dying.

Oh,

That's not spiritual.

I'll just sit and meditate.

So you use your spiritual life in some way to step out of the reality,

To bypass it instead of realizing that the trauma and the pain you carry is actually a gateway to deeper compassion.

That is a gateway to becoming more human and more fully present and actually to a kind of liberation.

I think that's such a key insight.

And it's something I really appreciate about the way that you teach and also probably a link between Buddhism and psychology.

Part of what I heard you pointing to was kind of the emotions and the struggles that we carry are in fact the gateway and not to be avoided.

And I feel like in your teachings it's so valuable to acknowledging and facing and allowing those difficult emotions or experiences that are there,

Which is,

You know,

Also relevant,

Of course,

In the psychological therapeutic path.

So I don't know,

Do you have thoughts on the importance of that kind of acknowledgement and allowing?

Yeah,

I mean,

In a certain way they're hardly different.

It's our human life that we have to pay attention to.

And if we want to be happy,

If we want our heart to be free,

If we want to love,

Which maybe is in the end the big question,

All of those ask that we take our human incarnation without a bypass as the place to embody those qualities of compassion and love.

It's not someplace else.

It's not in the Himalayas.

It's not in some cool Zen or Tibetan practice or something like that.

So I've been getting a lot of calls in these last months from foundations and big corporations and first responder groups and people all over who are tremendously anxious about the uncertainties that the pandemic and the fires and the,

You know,

Climate change and racial justice movement,

All those have just thrown so much at us.

And many,

Many people are suffering because they've also lost their jobs or lost their homes or lost security.

And the practices that I start with,

Which are these core practices,

Are to have people begin to close their eyes and sometimes to get themselves rooted or to become a little bit more steady in some way and almost envision that they have,

That they're a great tree that can send roots down into the earth or that they're sitting on the earth in some way so that they have a kind of inner strength or resource.

And then with this mindful,

Loving awareness,

We go through first your body.

What has it been holding?

Where are the areas of tension?

What's the trauma that you're carrying?

How are you holding it?

First and bring it into consciousness because it's there anyway.

And if we don't pay attention,

It makes us sick.

Then step by step to hold it with compassion and loving awareness,

To let it show itself rather than to try to get rid of it,

To feel it more fully step at a time.

And as you let it open more and more,

It starts to dissipate and release because the things that are closed is what makes us sick or stuck.

And then you start to realize that this movement of allowing for things to open with loving attention allows the body to unfold in amazing ways.

And of course in meditation that it can lead to the deepest states of the body dissolving into light and joy and bliss,

Those kinds of things for anyone who's interested.

And then we do the same with the heart.

What are all the things the heart's carrying?

Fear and longing and uncertainty and anger about things and,

You know,

Unexpressed creativity and tears and grief.

And first of all,

Just to say thank you to your heart for carrying so much.

And then,

Well,

What are the strong ones that need to be felt and take them one at a time and let them open and display themselves in image and feeling and so forth?

And as they do,

They get bigger and then they gradually open like the clouds and the sky around them of awareness holds them.

And then we do the same for the mind,

Which is like this,

You know,

The gerbil in the wheel is just spewing out plans and worries and ideas.

And you say thank you,

Thank you for trying to keep me safe.

I'm okay for now because that poor little overworked mind,

Thank you for all your creativity.

I appreciate it.

I will use you.

But right now it's okay.

You can relax a little bit.

So we do that and then we start to shift our identity from the body and the heart and the mind to become the loving witness of experience that we are actually,

We are consciousness.

That's what was born into our bodies.

That's what will leave our bodies when we die.

And if you don't believe that,

Just wait and see.

You'll see.

Check it out.

You know,

We're not made of kale and Big Macs.

It's just not your identity.

Who you are is consciousness itself inhabiting this form.

And so these meditations invite us then to not only turn toward what's difficult that we're carrying,

But teach us how to allow them to open and be held in the great field of compassion and understanding.

And then it allows us to do our work,

To love one another,

To engage in the world,

But in a much different and freer way.

And I think about it,

You know,

Mahatma Gandhi took one day a week in silence,

Even in the middle of deconstructing,

Taking apart the British Empire.

And people would come and say,

Gandhi ji,

There are millions of people out on the streets.

People are being killed.

They're shouting,

You must come help.

And he'd say,

I'm sorry,

It's Thursday.

This is my quiet day.

And in that one day a week,

Like the retreats I was talking about,

Or even like a short period of meditation where you step back,

He stepped out of all the ideas and thoughts and conflicts and got quiet enough to listen and say,

What's my deepest,

Best intention?

And what's my most strategic contribution?

How can I make the most helpful difference?

How can I respond?

And in the stillness,

There comes knowing and intuition and connecting with deeper wisdom that we all have when we listen.

So meditation isn't just about quieting yourself,

But it's quieting yourself so you connect to something deeper,

To the source of life and to the inherent wisdom and love.

That's who you really are.

Everything you were saying about the way of checking in with the body,

The heart,

The mind,

And seeing what's there and kind of naming and allowing that,

Accepting that,

It was just bringing up for me some kind of parallel,

I feel like in the current movement for racial justice.

I wonder if there's a parallel kind of on a societal level of this desire to name things that haven't been named or acknowledged about our history.

Absolutely.

As a country.

Because it's there and we're swimming in it.

And until we can name it,

It won't change.

And there's so much suffering.

Racism is the core wound of our American culture.

And it doesn't just affect people of color.

It diminishes and poisons all of us in these very deep ways.

James Baldwin wrote,

I imagine one of the reasons people cling to their hate and fear so stubbornly is they sense that once hate is gone,

They'll be forced to deal with their own pain.

And so when we live in racism and hate,

It's a deflection.

We blame other people for our own insecurity.

We're afraid we'll lose our status,

Our place or whatever.

So we blame the Mexicans or the immigrants or the gays and lesbians or the blacks or the browns or you know,

When I was growing up,

It was the communists who were the enemy du jour because we can't bear our humanity and the fact that our economy is uncertain.

And you know,

That the demographics are changing and we're not going to be an all white nation that we never were.

You know,

That beautiful line.

Let America become America again,

The America she never was from Langston Hughes.

And so to be able to turn toward the sufferings in ourselves and name them and in this society around is a radical act.

It's an act of liberation for all of us.

And it's a deep act of compassion to say we're in this together and we can see it clearly and we can do it differently.

I know you've done so much activism work in a lot of different spaces.

Do you want to talk about any of that in terms of anything how Buddhism has informed it or what what's top of mind for you today?

Yeah.

We're all activists or inactivists in some way or other,

But we're all engaged in our society and even if we live alone in our little hut and bury ourselves,

That's an activity.

It's a statement about what we care about.

There's a beautiful teaching from the Buddha about wise society where he says that if a society comes together in harmony,

Listens to one another with respect and departs in harmony,

They will prosper and not decline.

If a society cares for the vulnerable among them,

The women,

The children,

Those who are sick,

They will prosper and not decline.

If a society follows the wisdom of their elders and ancestors passed down for so long,

They will prosper and not decline.

If a society cares for the environment around them,

They will prosper and not decline.

Now the beautiful thing is that we all know this.

You hear this and this is not news.

I remember being at the first White House Buddhist leadership gathering a few years ago under a different president with President Obama and I was able to give kind of the concluding address or summary.

And I mentioned these teachings,

But they're not different than the teachings of the Iroquois native elders or of the Chinese masters of Confucius and Laozi or the African elders and so forth.

I said,

But there is a difference perhaps.

And that is that along with describing these,

The Buddha then offered practices and trainings to embody them so that not only are they ideal that we all can know and aspire to,

But here's a way to train compassion and we can put it in every school in America,

Social and emotional learning so our children really feel that interconnection as maybe happened back in days that were again,

Part of a more indigenous or earlier world.

There are ways to train attention to one another.

There are ways to solve conflicts.

Here are the practices for it.

For activism,

Because this is a time that really calls us to stand up.

And if you look again in the Buddhist history and the stories that are told,

The Buddha actually stepped out to try to stop wars and battles and spoke with the kings and ministers that he felt would listen to him about the ways that they were being misguided and how to tend their kingdom and their people.

He also was a powerful activist against the caste system,

Which was basically India's form still is of racism,

Primarily those who are darker skinned because there's a colorism in it between the Brahmins and the lower caste and the untouchables.

If you can imagine even now being born in an untouchable body in India,

In the rural villages where this still holds sway,

If your shadow passes over the food of a Brahmin or someone who's a higher caste,

It pollutes it and they have to throw it away.

So imagine some little girl walking along and even just her shadow is a pollution.

And the Buddha said,

No,

Come and join our order.

And he gave ordination to those who were the outcasts,

The untouchables as they're called.

And then he ordained some of the princes following that,

Which meant since the hierarchy is in the order of when you ordained that these great princes had to get down on their hands and knees and bow to the person who cleaned the stable or was the,

You know,

The untouchable in the kingdom.

And he said,

No,

When people ask him,

Nobility is not by birth,

Not by status of where you were born or what family.

He said,

There's only one true nobility.

It's the nobility of heart.

And if you have kindness and generosity,

If you carry wisdom and love,

Then this is what makes you a noble being.

So when you approach activism,

You can approach it in an angry way.

And anger has its place.

It's not all bad,

But there's a whole other way to approach activism because that both burns you out.

And we've had tons of burned out activists come on our retreats.

And it also creates its opposite.

If you get really angry and violent,

Then what do you expect in return?

Molly Ivins,

The great activist from Texas,

She says,

You know,

When you go out on the streets,

When you become an activist,

Don't forget to have fun doing it and then tell everybody else that this is something you can do for fun.

Now,

That's kind of an astonishing thing for her to say.

Yeah.

Because people get so damn self-righteous about it.

But actually every side has some points.

No matter how terrible,

Every side says underneath something that needs to be felt or understood or recognized or listened to or even respected in some parts.

I mean,

Some of them may be very destructive,

But there are other points.

And I remember being in one of many,

Many demonstrations with my daughter who runs a beautiful nonprofit organization.

She's a young Berkeley lawyer.

And she and a bunch of her compadres were at the San Francisco airport helping the protests in the early years of the Trump presidency against people coming in from these predominantly Muslim countries.

It's 2000 people in the airport.

At our gate,

There were like 400 people and all these young lawyers.

Her work is to get asylum for people from around the world whose lives are in danger.

There are places called Oasis Legal Services,

And it's an oasis for these people,

Like a gay guy from Uganda who'd be stoned to death if he went back.

So we're all there and people are shouting with their signs,

No ban,

No fear,

Refugees,

Welcome here,

You know,

And the usual kind of demonstration.

And in the middle of our demonstration at that gate,

There was a New Orleans jazz band.

And so the drummer kicked in and he gave us a little rhythm for our chant.

And then the trumpeter played a riff on top and the sax player played some melody.

Pretty soon we were going,

No ban,

No fear,

Refugees,

Welcome here.

Made a whole tune out of it.

We're all singing.

The cops start smiling.

The security guards are dancing with us.

We were there.

We were standing up.

We were not going away.

It mattered to us.

We were going to be there until these people got their freedom.

But we were doing it with love.

We were doing it artfully.

And it changed the entire dynamic.

So yes,

Go out on the streets or yes,

You know,

I've got a project to get all the Buddhist and yoga teachers of America to get their students to help people in their communities out to vote.

Do it,

But do it out of love.

That's what's infectious.

And that's really what changes us.

Beautiful.

I love that spirit.

I'll just ask one final question as relates to contemplative science,

Actually.

I feel like oftentimes in the field,

We're not necessarily measuring the most relevant outcomes.

And sometimes it's because we don't necessarily have good ways to measure them.

But from your perspective as a teacher and in your students,

What would you say are the most important changes that you see that we could try to measure as a field to get a sense of the development on this path or just the main outcomes for meditation that are most important?

Well,

I'm going to put it in a very colloquial way first.

If you want to know about a great master,

Some Tibetan Lama or some great Zen master or some great,

You know,

Meditation master of other traditions,

Talk to their wife or their husband,

Because that's really where the measurement matters.

I remember standing at a gathering,

It was a soiree that my dear friend Angie Terriot had.

She and her husband,

Dick Terriot,

Was the publisher of the San Francisco Chronicle.

And so it was a gathering with Robert Bly,

With whom I'd taught with for many years,

And Michael Mead starting that men's movement in the 80s.

And I just come back from being at one of the events in the woods that we led for many years,

Many of them with kids coming out of street gangs and things like that,

To get them to have an initiation or a different experience of how we could live together.

And it was the wife of one of the celebrities that was there,

Who was a very strong feminist saying,

It weirds me out that these men are going out in the woods and beating drums.

And,

You know,

I mean,

They've so much trouble with men anyway,

From the feminist perspective.

And this is just kind of,

It's all going to make it worse.

And what are they doing out there?

And then my ex-wife spoke up and she said,

I don't know what they do out there,

But he's a lot nicer when he comes back.

So this is the measurement.

Yes,

We can dissolve the body into light.

Yes,

We can go into deep samadhi and change our breath and lower our pulse.

And yes,

You know,

Maybe we can even get deeper intuition and feel into the emotions and minds of others and all those kind of cool things.

What matters?

Do we love well?

Are we humane and decent human beings?

That's what we need to measure.

Yeah,

That's fantastic.

I think there's been such an emphasis in this field of merging the,

What's generally called the first person and the third person perspective.

So kind of subjective of your own view.

And then the third person,

Like scientific view,

Like neuroscience or other sorts of measurements like that.

But what you're raising up is what we sometimes call the second person view of just another person.

And that's so important.

Thank you.

There's where you get the real story.

Yes,

We need to weave that into the research.

Well,

Thank you so much,

Jack.

This has been amazing.

I really appreciate you taking the time and thanks for all of your wisdom that you're sharing in the world.

My pleasure.

And I,

You know,

I'm so appreciative of mind and life giving birth to this whole field of both contemplative science and neuroscience coming together,

Eastern,

Western,

And in some ways also to the field of affective neurobiology,

To the whole field of emotions and so forth.

And life has really been at the forefront with His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Francesca Durella and Richie Davidson and all the other characters that we know who've been part of it.

And this is a great treasury that we have as human beings to draw upon and now bringing the treasure house of the contemplatives together with modern science.

We need it because it's so obvious that no amount of outer development of the artificial intelligence and internet and computers and nanotechnology and biotechnology and space technology are going to stop continuing warfare and racism,

You know,

And economic injustice and climate change and environmental destruction because these are all rooted in the human heart,

You know,

As the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff said at one point,

We're a nation of nuclear giants and ethical infants.

And so what's now called upon us as human beings is to match this remarkable outer development that we have with an inner development.

That's our task on this earth.

And Mind Life and the things that we're doing together is really a part of making that happen.

So thank you.

This episode was edited and produced by me and Phil Walker.

Music on the show is from Blue Dot Sessions and Universal.

Mind and Life is a production of the Mind and Life Institute.

4.9 (425)

Recent Reviews

Siobhán

January 4, 2024

Incredible

Judy

December 2, 2023

Love the sense of acceptance

Cary

July 14, 2023

🙏

Sharon

July 1, 2023

Thank You

Marcia

December 19, 2022

Integrative excellence🪷 I am deeply grateful for what this touches 🙏🏻

lesley

May 11, 2022

Awesome. Great interview- good questions -relevant to these difficult times. Love Jack’s humour and realness.

Heidi

May 10, 2022

Wow wow wow! Great, informative talk, thank you!!

Tammy

April 13, 2022

Powerful and inspiring