1:02:19

1:02:19

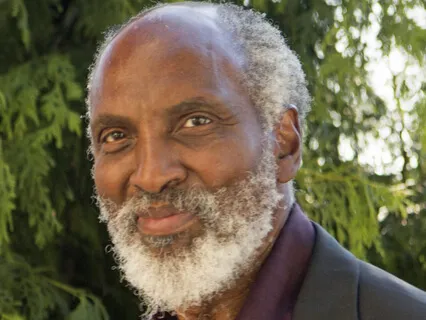

Othering And Belonging - John Powell

Rated

4.9

Type

talks

Activity

Meditation

Suitable for

Everyone

Plays

1.1k

In this episode, Wendy speaks with law professor and civil rights expert John A. Powell about his work at the intersection of social justice and spirituality. They discuss a wide range of topics, including the problem of othering; the roots of whiteness; how our minds create mental schemas; implicit bias and how to change it; the importance of narrative and bridging stories, and the role of leadership; identity politics, and more.

PoliticsOtheringBiasSocial JusticeStorytellingRacismIdentitySocietyLeadershipEnlightenmentClimate ChangeTechnologyDemographicsScienceBridging PoliticsImplicit BiasImportance Of StorytellingSpiritual ConnectivitySystemic RacismIdentity ConstitutionIntertwined StoriesSelvesScience And SpiritualityGlobalizationsSocietal ChangesSpiritual PracticesTechnology Impact On SocietySpirits

Meet your Teacher

Mind & Life Institute

Charlottesville, VA, USA