Three Essential Practices

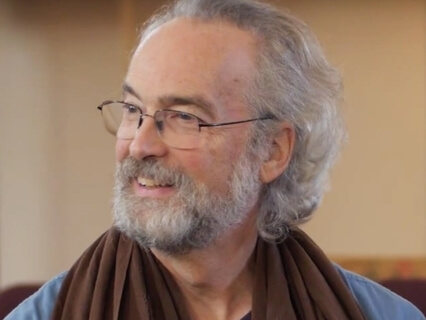

by Doug Kraft

The so-called Four Noble Truths are the core of the Buddha’s teaching. They are not capital “T” truths, but simple meditation instructions. The first three could be translated as turning toward, relaxing into, and savoring. And they are powerful.

Transcript

So,

We're going to be working with three little phrases tonight.

Turning towards,

Relaxing into,

And then savoring peace.

And so,

I want to explore these and develop in a lot of different ways.

But as a place to begin,

I'd really like you just to come back to just where you are right at this moment.

And where you are with your practice.

And as we discuss these as we go through the evening,

To keep coming back to see where you are in relation to these.

Which ones work for you and which ones you tend to move away from.

So just thinking about it right now,

When there's a hindrance comes up in meditation or there's some distress in your life,

How natural,

How organic,

How spontaneous it is for you to actually turn towards that distress and open up.

And how much more likely is it that you might turn away or try to get on top of or control it or get out of the way.

So just even looking at your own practice here,

Is there an instinct to turn towards it?

Because I think the biological one is to go the other way.

And when there is some tension that comes up in your system,

How often do you think that your first response is actually just to relax?

And how often is your natural response to,

Oh I've got to fix that or I don't like it,

Or let's get out of here or push or pull or something else.

And when there are some peaceful moments that come up in meditation or during the day,

How often do you just savor those?

And how often do you,

Like me,

Just kind of ignore them?

Or maybe even look at it as a moment of boredom.

So I'll just kind of get a sense of that.

And I'll unpack more about what those mean but I just want you to be looking at those in that particular way.

So last night I was telling something of the Buddha's story and part of what I hope you get out of it is that it's,

He really was a very human guy.

I mean what he did was quite extraordinary.

But if you look at all those various parts of it,

You know,

Hours before his full of enlightenment,

He was flooded with these hindrances.

So when you feel flooded with hindrances,

Just know you're in good company.

He spent years,

You know,

Fervently dedicated to a practice that he ultimately figured out didn't work.

So I think all of us have had times of taking some practice and then what happens when you discover it doesn't work.

He grew up in a family where there seemed to be at least the average number of dysfunctions,

Maybe more.

I mean not many of us have a cousin or brother-in-law who wants to kill us at some point.

So he grew up with all of that.

He made mistakes even after his enlightenment,

I just love the story of Upaka,

You know,

Just things that,

Whatever friend,

And walking on down the road.

You know he completely missed what was going on.

What I can't say for sure it's really in there,

But what I really imagine was in there and all of that stuff,

Though he just had an enormous kind of curiosity and interest to see what was going on.

And when you've got that,

When things go awry,

You actually learn from it and you grow wiser out of it.

So it really wasn't that different from us.

So this evening what I want to do is then pick up where we left off last night,

Was that first successful teaching,

Not his first teaching but his first one that really worked.

And look into the core of that,

The essence of it.

What is it that made that so powerful?

And what I think that was were these three practices that I was mentioning before,

Turning towards,

Relaxing into,

And savoring the peace.

And those of course are very vernacular translations of lying,

But we'll look at the text a little bit more.

I got interested in this whole topic because the Buddha drew on lots and lots of different practices.

Many of the ones he taught weren't the ones that he created.

He pulled them from all kinds of places and he taught different people different ways.

But for me there is still something,

There is some Buddhist flavor that comes through all of them and I was trying to pinpoint what it was that made those feel like they were Buddhist rather than something else.

And ultimately what it came down to was these three.

And I think for all of us,

Because all of you have practices that are getting to the place and maybe long past the place,

Where it's important to subtly and then sometimes not so subtly adapt the practices to you and what you need.

And there's ways,

Particularly early on you do too much adaptation and you can really get way away from what's effective.

But eventually you really have to do that.

And I think these three practices give you a kind of a benchmark or a guidance or a way of seeing if you still have those three elements in there.

There are lots of ways to implement them but if you still have three elements then I think you're basically within what feels like me,

This really effective approach,

Not only to meditation but to life that has these elements in it.

So these three essential practices,

They come down to us under the label of Four Noble Truths.

But I think that whole title Four Noble Truths is misleading.

Four Noble Truths,

First of all they aren't truths with a capital T.

They aren't declarations about ultimate reality.

They aren't metaphysical descriptions of how the world really is out there beyond all of us.

They are really in some ways kind of almost mundane,

Very ordinary observations of life around us.

We all suffer from time to time.

Duh.

Relaxation feels better than uptightness.

Those aren't big huge principles.

So rather than Noble Truths they are just really ordinary observations.

And they aren't noble.

They aren't noble at all.

In Pali,

The language that these are recorded in,

The noble doesn't refer to the truth.

The noble refers to the mind and heart of the person who engages these observations wisely.

So each of these observations has a very specific practice that is associated with it.

And when you engage that practice in an effective way,

It ennobles,

It uplifts,

It has a tendency to free the mind.

So it's not about the observation but it's about the mind of the yogi,

The mind of the meditator.

Stephen Batchelor refers to them as the Four Ennobling.

So ennobling kind of puts the emphasis back on the one who is engaged in them rather than focus it on the observation itself.

Four Ennobling Truths,

Four Ennobling Observations,

There aren't four,

There are three.

So the supposed fourth one is the Eightfold Path.

The Eightfold Path is not an observation,

It's not a truth.

I think of it as a checklist.

So if you engage the first three practices and your practice still gets stuck as it does from time to time or gets bogged down or it's not working so effectively,

The Buddha provided this checklist of stuff that you can use to go back and look at your practice and see if it needs to be fine-tuned.

He gives the eight areas to look at.

So I think what happened with these is that in the West,

Religion is usually defined by a set of beliefs or statement of faith or metaphysical manifestos,

I believe in one God the Father Almighty,

Maker of heaven and earth.

They're usually declarations about things that you can't prove or disprove empirically.

And so,

You know,

Five hundred years ago when Westerners began to really sort of engage and come in contact with these practices and begin to try to translate them,

They didn't really understand what Buddhism was about.

So when they saw these things,

They took these observations and kind of elevated them into a capital P,

Truth,

And they just kind of skipped over the practice altogether.

It was associated with it.

But I do think these three practices are the foundation,

The real foundation of Buddhist practice.

To understand them,

There are three Pali terms that's helpful to be familiar with.

I would rather just give you the Pali because they don't translate really well into English.

The three terms are Dukkha,

Kanha,

And Narodha.

So there's those three words and then there are three practices which translated into English are understand,

Abandon,

And realize.

So what the Buddha said was that Dukkha is to be understood,

Kanha is to be abandoned,

And Narodha is to be understood.

So that's closer to the original language about how they're described.

So let me just unpack these.

So the first one is understanding Dukkha.

So you guys know a lot of this stuff.

So what is Dukkha?

What is Dukkha?

Suffering.

Conflict.

Tension.

Stress.

No,

No,

No,

No.

Tension is stress.

Tension is stress.

Tension is Tannha.

Well I was going to pee.

You were moving ahead.

We'll just stay with Dukkha for now.

Other translations of Dukkha?

Dissatisfaction.

Crazy wheel.

Crazy wheel?

Or creaky wheel.

Oh creaky wheel,

Yes.

Did I talk about that?

Okay.

Grinding.

Grinding.

Yeah,

The origin of the term,

What it literally means is it's the hole in the center of a wheel,

You know,

The axle goes in and you know,

It's greased,

Etc.

And so the way I first heard it was if the hole is slightly off center,

You know,

Then it presses and grinds as it turns.

Lee Brazington,

I heard him recently say it actually refers to a lot of sand and gravel getting inside that so it,

Which I think gives the flavor of it.

The difficulty of translating into English is it does have this wide range,

You know,

From out and out,

You know,

Severe pain to just subtle annoyance.

Lee Brazington has this little page on his website that's kind of fun to read.

He makes the case,

He says the best English word that we have for translating Dukkha,

If you really want to get the flavor of what he is,

Is bummer.

Bummer.

And if you think about it,

It's really great because bummer has that wide range of meaning,

You know,

My best friend died,

Oh wow,

What a bummer.

I dropped almond butter on my sandal,

Oh bummer.

You know,

It really works for that whole wide range.

And also the other lovely thing about bummer is it really has a tendency to push your attention back to the mind of the perceiver,

You know.

Oh I got this almond on my sandal,

Oh it's just a sandal,

Don't bum yourself out,

You know,

It really reflects back.

And he goes on to say that of course he's not going to convince a lot of scholars that they ought to use the term.

It's a better one than most of them.

Yeah,

No,

It really works,

You get the whole flavor.

And for me I also like it because it's got a playful element in it and I think sometimes it just really gets ground down a little bit by it.

So the Buddha didn't say that life is a bummer,

He just said that life has bummers.

And it's not a profound observation and there's nothing noble about it,

You know,

Quite until there's nothing noble about bellyaches or broken bones or grief or death or all that,

You know,

Some of them are just a drag.

So his first practice is to understand dukkha,

To understand bummers,

To understand suffering and dissatisfaction.

The only tricky thing about this is,

Let me just ask you this,

What does it mean to understand something,

What does it mean if you say,

You know,

I really understand Eric,

What does that mean?

I think it means you grasp it at an intuitive level,

Not just analytical.

I think both are multiple spheres of understanding.

You have to work together.

It's also really open to him,

To be able to know him.

You can't have an empathetic understanding of somebody if there's not a certain amount of openness.

It's a quality of being with rather than over against or some other kind of relationship.

It's I'm with them,

I'm with it.

That's right.

In the experience.

And there's a clarification that becomes very clear.

Yeah,

Yeah,

Yeah.

So there's an identification of that being?

Well it could be,

I think it's sort of being against the slip.

Once it goes into identification it starts to slide a little bit into delusion.

But it goes right up to that edge.

Are you aware of the nuances?

Yeah,

Yeah.

Yeah you kind of know,

You know,

You have some sense of how he ticks.

You know,

His fears,

Aspirations,

Motivations,

All that stuff.

And there's almost a sort of implication of,

There's a kind of little bit of a heartful element to it.

If you play with the word,

It's to stand under which would imply then to be inside of it.

Be with it in a different kind of way.

Yeah,

Yeah,

Yeah.

Because for me the only difficulty,

And you've seen past it,

Is understand if you just go over it quickly it can begin to sound a little intellectual.

And that's the one difficulty with that translation but it really is much more what you're talking about,

Standing under,

Being with,

All that stuff.

So what the Buddha was saying was that in order to fully awaken we need to understand suffering.

Right?

So it requires an openness.

You know,

You can't distance,

You have to stand under it,

You have to be with it.

It takes,

You can't do it if there's a lot of aversion.

So it really,

So that's where I get to this thing of turning towards.

You have to return towards and open up.

If you're busy trying to get away from it or understand it or analyze it or rise above it or fix it or all that sort of stuff,

You're not going to understand it in this sort of multi-dimensional way that Eric and the rest of you are referring to with all those different dimensions.

So it's almost like with understand,

It's almost like you sort of have to take it in and feel it on its own terms.

So in your own practice,

You know,

Just to hear the last couple of days,

Are there times when you have spontaneously done that?

There's been some difficulty come up and you just kind of soften into it?

Yeah,

Can a few sort of describe some of those?

Well,

I noticed it straight off on the first night when you had us do the expansion.

I can't remember exactly what the context of it was,

But I was feeling this great expansion,

Just being with it and opening further and further,

And it came to this steel banging around my neck where that just stopped and it's just the sight of an end to me and the brain stem I'm working with.

And it was like,

Oh wow,

It was that graphic,

It was just so graphic.

But what struck me was a wonder,

A wonder if I can,

If it will open up to that expansion.

I don't know if I can tell you how it will open up to that expansion,

But I can tell you how it will open up to that expansion.

So it's got a little bit of that,

It's sort of a curiosity,

And just,

Oh yeah.

Other examples?

Yeah,

As you can feel in both those examples with Erica and also with Chris,

That the only way you can get it is that kind of opening up and feeling it on its own terms to get what's really going on there.

Other examples?

I was in the quantum estate and the image of one of my children came up and it was like,

No,

I'm not getting into that.

Shoo,

Shoo,

Shoo.

And it was turning into that,

What it actually did was open up both compassion and some new insight in relation to that.

So it was like what you said the other night,

The mind wants to bring up to us that we need to see,

Experience,

Know,

Understand.

And we didn't talk about it a lot,

But there was that Asperger's aspect of the hindrances,

If we don't open up to it,

It's like the system doesn't get it,

That you don't want to hear it.

We just keep finding ways to bring it back.

I had a moment in meditation today where I get social anxiety sometimes around lots of people and I had the most intense form of it I've ever had in my life.

It was like a full on panic attack and it felt like my energy system,

It felt like an owl in my head got twisted 180 degrees.

And I felt like I was on a ship,

My whole system was going like this.

And all I wanted to do was run out with the entire retreat center and that's what I want to do when I'm having a life with people and I just sat there and tried a six-hour,

But it was so intense I couldn't even remember the six hours.

I just sat and finally I calmed down enough to be able to six-hour,

But it was a totally wild experience.

That's really great,

That's really lovely.

It really did work,

When it's so intense,

Because under that sort of tense pressure it's like we always regress,

So the things you learn last kind of fall overboard.

But there was enough wisdom there that you actually stayed with it and gave it some space until gradually the system calmed down enough so it could bring back in.

I just want to tell you about Rijerod,

Because 20 years ago I was on a three-month retreat and I went into that kind of experience.

So things have come a long way.

That was off the reservation.

The other thing that's great with all the examples that you're given is that you can see how the wired in biological response is to turn away.

And so the practice is very simple in some ways,

But it's not always easy.

Are there other examples?

I'm kind of relaxing into a lot of expectations that I had prior to the retreat,

And then completely upside down now.

Think about how the retreat would go,

And my meditation and things like that.

It's completely different.

Oh my goodness.

Well everybody wants to know the details of that.

I mean,

I think that things would go great,

But I have a lot of progress and things like that in a classical sense.

But I'm not radiating anything.

My awareness feels incredibly weak.

I've just got hindrances coming up constantly.

I can't sit for more than 45 minutes.

I can stretch an hour and a half if I really focus.

So yeah,

It's completely different.

But it's kind of mixed in with all the bit of tension around,

Well I've travelled so far,

I've got to make the most of it,

I'm with Doug,

I've got to make the most of it.

All these kind of desires and expectations and all this stuff has gone completely the opposite way.

It's a fact.

And then I get to bring up a lot of doubt about myself and my meditation.

So here's the question.

How much can you actually turn towards that and open up and how much does it just have you back against the wall at the moment?

Slowly.

Yeah,

Yeah.

Though this is not easy stuff.

This is not easy stuff.

Yeah,

There's plenty of time.

Yeah,

I'm going to go back to the beginning.

You know,

The story's going on,

I get to the end of the retreat and it's just exactly like it is in day three,

Then it's important that I don't judge myself too harshly.

Yeah,

Well if you do just have a sense of humor about the judgments.

The mind does that.

You know,

When I went to Thailand,

I had one of those two,

But it was this sort of big thing.

I was actually on sabbatical from the church I was serving and after about a week and a half I just wanted to fly home.

But I got all that money and what am I going to tell people?

It was almost like,

You know,

The aversion for going back was bigger than the aversion for staying.

It was the only thing that kept me on there.

And the other thing,

Just in terms of encouragement,

I have seen people come into retreats and everything just goes perfectly and smoothly.

You know,

It's just really lovely.

And they go back out and they go back into life and nothing's changed.

And I've seen people go into retreats and they struggle.

They can't stay with a map for more than two minutes and they flop around all over the place and then they go back out and everything is different.

Everything is different.

So when all that stuff is coming up,

You don't necessarily get the goodies,

But you get this really deep work.

To give an example,

When we lived in Oregon there was this big name Buddhist,

Or Burmese teacher and so it was a three week that we were going to go to.

And it was brutal.

You know,

It was this Burmese,

You know,

Take no guff kind of thing.

After two days I just said,

I can't do this.

And I drove home and Pat was good enough to say,

Go Pat!

Pat,

A little bite.

It was what you say,

It was really a tough retreat.

And yet,

You know,

I got a punch of stuff.

It was just one of those experiences.

These aren't tough retreats.

These are very wonderful retreats and then almost every retreat somebody wants to leave them.

So here's the trick,

Here's what we do.

I'll just tell you the inside trick.

So they come up to me and they say,

I really,

I think I'm good.

So,

OK,

So why don't you go outside and take a walk and walk around the place and we'll get you an interview,

But just relax and enjoy the outside.

So then I go and talk to the teacher and then the person walks around and then they might talk to the teacher or they come back to me and they go,

I think I'm going to stay.

I'll try another few hours.

Or they go and talk to the teacher,

But rarely anybody ever leaves these retreats.

The personal retreats.

OK,

Good,

Good,

Good.

So I think you've got the flavor of it.

And what I love about some of these examples too is it's very easy to say,

You know,

Just relax and open up to it,

But it's not easy,

Particularly when all their stuff is being thrown up in your face.

Well,

It's counter-biological,

You know,

The body is wired to run from discomfort.

And if we didn't have that we would destroy our bodies really quickly.

I mean,

It makes a lot of sense.

There are people who don't actually feel pain,

You know,

And they're usually physically erect because they burn their hands and cut,

They're not aware of it.

So it's just wired into us.

It's a survival mechanism,

But it's not a,

I was trying to do the parallel word for thrival,

Thrival word.

It's about surviving,

It's not about thriving.

Meditation is about thriving.

You need a different set of instincts.

And it takes a while to cultivate,

To trust it.

But you learn a lot from this,

So it's great.

So turning towards,

And as you begin to understand bhāmas,

Suffering,

Dukkha,

Dissatisfaction,

It's not just the discomfort of it,

But as you keep doing that you get to the point where you begin to see the discomfort rising,

The bhāmas rising and then fading,

Coming and going and coming and going.

And that's where the real wisdom comes in,

When you can see them coming and going.

And when that happens what you begin to see is that our experience of discomfort always arises out of tanha.

So this brings us to the second practice.

The Buddha described the second practice as the origin of the experience of suffering is tanha.

Tanha must be abandoned.

So what's tanha?

Tension.

Pardon?

Tension.

Tension.

Mental,

Physical,

Or any kind.

Right.

Craving.

Craving,

Yeah.

So tanha covers this whole range of stuff and craving is kind of the extreme end of it,

But it's probably one of the most common translations of it.

I call it urges.

Urges?

Urges.

Yeah.

Pemaśodara uses a useful term,

You use their face,

Sometimes you call them hooks.

Hooks,

Yeah.

You know,

Something that sort of grabs you.

But the hook comes after the urge.

There's an urge and then the hook.

Well okay,

So that's for everybody to explore and see.

No,

No,

No,

You're not even given a secret away,

Because I think it arises different ways for different people.

Yeah.

So tanha is an instinctual and I think it's a biologically based contraction and it is pre-conceptual and it is pre-verbal.

Probably some of the most blatant examples are you're driving down the road and somebody cuts you off in the lane of traffic and what happens?

Your hands tighten on the steering wheel.

It's not like you think about it.

The body just goes,

Like that.

Or if there's something that's very attractive that comes along,

You know,

The body just goes,

Okay.

So when you say think about it,

So there's cognitive,

It's not pre-cognitive.

Yeah it is.

It is pre-cognitive.

It is pre-cognitive.

How can it,

If the mind is cognating,

How can,

Is it just like,

Because if there's a perception there's a cognition and we may not be aware of it,

But I mean I don't know neurology that well,

But I think there is some kind of a cognitive.

No,

No,

There's actually spindles in there.

So it's pre-verbal.

Yeah,

Yeah,

Yeah.

And so,

Okay,

I may need to back up a little bit because sometimes I get a little confused about cognition.

That cognition is not necessarily verbal thinking.

So it's just like knowing something.

So citta,

Mind,

Is this vast field that's got memories and impulses and all kinds of stuff going through it.

Okay,

I look at that as mano,

And the mano is affecting the citta.

Let's have a discussion on this offline because I'd like to really get your understanding of that.

Okay,

Okay.

Yeah.

Mine comes from Utejani,

I think yours comes from,

It would be interesting just to compare those two traditions.

So the tightness,

It's really important to realize it's not willful.

It just happens.

And we can have lots of thoughts and decisions that come after that,

But the impulse itself is,

It just… It covers this in a colloquial kind of way,

But it's my instinct to go for or away or to feel without having pre-verbally to judge it.

Yeah.

I'm there with it.

Right.

Yes?

But I experience a lot that the body just expresses it and I have no connection with what I would call an intuition.

You were saying instinct.

That's what I'm saying.

It's my body response that I in some ways don't even control.

That's right.

Right.

Yeah.

Yeah,

It's reflexive in that sense,

Like an instinct is.

It comes out of the wiring.

I think a lot of it bypasses the frontal lobes,

Which is where our awareness of actually looking at it just… An example I think probably a lot of you have had is walking through the woods and you're walking along and you jump and then you notice a snake and then you notice it's not a snake,

It's a stick.

And it kind of goes in that order.

First there's a reflex and then there's a little bit of a recognition and you realize it was wrong.

So it actually comes first.

So what are some other examples of… Question on that.

Would an enlightened being respond the same way in a sort of automatic impulsive jump in fire or the snake?

Give me a few more years and I'll let you know.

My guess is yes to a certain degree,

To the extent that it's wired in.

And part of the reason I say it,

There are these lovely passages in the suttas where the Buddha is given a Dhamma talk,

A whole bunch of nuns,

And Mara appears.

Mara is the sort of embodiment of delusion.

And the Buddha says,

Mara,

I see you.

And then typically once Mara's seeing kind of slinks away.

Well if you translate that into modern psychology,

Using that language,

The Buddha is there and he experiences a delusion.

And the difference between him and us is he immediately recognizes a delusion as a delusion.

He's not fooled by it.

And so I think what happens with… I would think with enlightened beings is that underlying wiring may still be there and so it will trigger those things.

But there's the clarity to see it for what it is,

So they're not fooled by it.

And there's a lot of descriptions about moving towards enlightenment,

That's what happens is that the time between when something comes up and you get triggered and when you recognize what it is gets smaller and smaller and smaller.

But I think that there's probably some of it that's still there.

And I think I can say this safely,

I think Bhante would disagree with me on that.

Why?

Because I think what he would say is that a full enlightened being,

That greed,

Hatred and delusion are completely gone.

And so it kind of gets down to nitpicking about what that really is.

I think there is a biological reflex that can still be there that does tighten.

You just don't buy it.

But it's not like the impulse is gone completely.

So I may be able to talk him out of it,

But I don't know.

I've had this conversation,

We haven't quite gotten there yet.

So are there examples of atthana?

Wanting,

Not wanting?

Yeah,

Yeah.

Thoughts create tension.

What thoughts?

Thoughts create tension and thoughts can actually arise out of tension so it can be a whole,

They can work both ways.

If there's tension in the system,

Sometimes the system will try to bleed it off through thought and we can have thoughts that trigger more tension.

It can work both ways.

We were talking earlier today about different kinds of thoughts and I can't remember if you covered this part,

But without any tension at all can you still have certain kinds of thoughts like the kind of non-hijacking thoughts or if you have no tension or all thoughts that you can still have without there?

I'll try and see if we can do this quickly.

I don't want to get too far off track,

But it's really a fascinating part because thoughts get a lot of bad press.

And so what we were talking about is three different kinds of thoughts.

So there's one that's called vikaka and what that is,

It's just a labeling.

Frogs.

Breeze.

You know,

There's an experience and the mind just puts a label on it.

There's a little bit of tension in it,

But it's very,

Very little and it's really,

It's not problematic.

There's another kind of thought that's called vikara and it's a type of thinking,

So this is the shared secret that we do a lot of thinking when we're meditating.

So you're sitting there.

4.5 (14)

Recent Reviews

Ahimsa

November 6, 2024

Informative and appreciated. www.gratefulness.org, ahimsa of www.compassioncourse.org

Cary

January 5, 2023

Thanks 🙏