1:26:47

1:26:47

Inner Landscape, Part 1

by Doug Kraft

Rated

5

Type

talks

Activity

Meditation

Suitable for

Everyone

Plays

508

This three-part talk is a 3-way conversation between our direct experience, the Buddha’s comments on experience, and science. It explores the components of phenomena (khanda), how to work with them, and ways to skillfully alleviate suffering.

Three Part TalkExperienceBuddhismScienceFive KhandhasSufferingMeditationPerceptionEmpathyOvercoming SufferingBuddhist TeachingsReality PerceptionInner ExperienceCognitive DistortionsEmpathy In ContextConversationsInner LandscapesScientific PerspectivesTranslations

Meet your Teacher

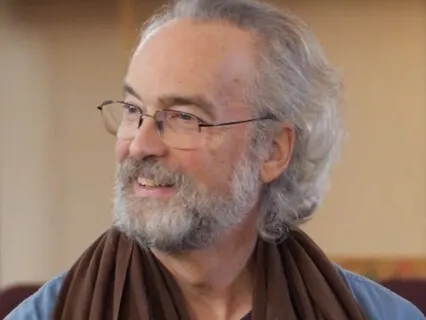

Doug Kraft

Sacramento, CA, USA