How Buddhism Entered The World

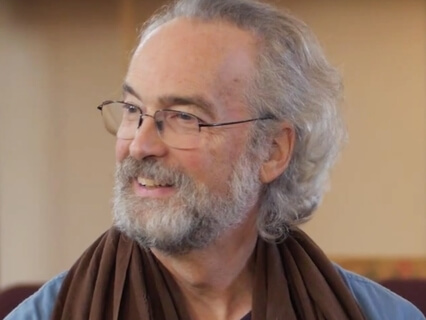

by Doug Kraft

Reconstructing the historical Buddha — who he was, the culture and traditions that shaped him, and how he would have been perceived by his contemporaries — help give insights into how he thought and what he taught.

Transcript

So,

Last night we were kind of going into the weeds,

Some of the details,

Particularly hindrances,

Etc.

And I know there's some people actually learn best by getting all the details together and from that they sort of extrapolate out what the larger picture is.

And there are other people that kind of need the larger picture before they can actually get a hold of the details.

They're just different learning styles and ways different people's minds work.

Tonight and tomorrow I want to sort of go out and really get the large picture of what's going on.

As I said when I was coming up for a title for this,

The one I really liked was how Buddhism came into the world.

So what was it he was really,

Really about?

It's difficult to project ourselves back two and a half thousand years,

A different age,

A different time,

A different country,

A different continent,

A different political structure,

A whole different societal system,

A whole different economy,

A very different worldview.

To try to project our back there and then intuit the innermost thoughts of a spiritual innovator like the Buddha.

And so we end up projecting a lot of stuff on top of that.

And the information is scant but we can put some pieces together.

And even if we get a little bit more kind of sense of what it is he actually experienced and also how his contemporaries heard his instructions,

Because he wasn't talking to us,

He was talking to people he knew there.

If we can understand how they heard this then it becomes a lot easier to figure out how that relates to us today in our situation.

So tonight I just want to tell you a little bit about his story.

We don't actually know what his given name was.

Tradition said it was Siddhartha but Siddha means accomplish and Artha means goal.

So Siddhartha means one who accomplished his goal.

So to me that sounds very much not like a given name but like a spiritual name that was given to a yogi after he attained something great later in life.

It's hard to imagine parents lifting up their newborn child and saying,

Ah,

You have accomplished everything you have for life,

We're going to call you Siddhartha.

We're pretty confident that his family name was Gautama and that his clan name was Sakya.

The Sakyas were a clan of warriors,

A clan of fighters that occupied a small area of the northern part of the Ganges River Valley about two or three thousand years ago.

So he was born into a tribe of fighters.

That's what he came into.

Someone says that his father,

Sadalma,

Was a king.

Well,

I'm not so sure.

At least not a king how we understand it.

At that time the Ganges Valley was a collection of relatively autonomous principalities and his father was the head guy of one of these.

So he was really much less of a king and more of like an independent duke.

Or maybe a better way to say it,

He was like a clan chieftain.

But not a king in the sense that we usually think of it in the West.

His father was said to be highly esteemed by those around him and that seems credible to me.

It would take somebody who is highly esteemed to keep a tribe of warriors together.

One says,

I'm just going to refer to him as Sri Gautama for a while here.

We don't know what his given name was.

And Sri is sort of a generic,

Sort of like Mr.

In some situations it has more elevated quality but often times it's just like Mr.

So.

The later tradition says that Sri Gautama grew up in a palace.

But there was certainly no draw bridges or moats or high turrets or high ramparts.

Erica and I had lunch at his house about eleven years ago.

His homestead in Kiplavatthu,

Which is right along the border between Nepal and India,

The homestead in Kiplavatthu had really been lost in history until about fifty or sixty years ago.

Some archeologists figured out where it was in this seemingly empty field.

And they excavated down about four or five feet and were able to expose the base of all the walls.

And so if you go there today you look out and you see kind of like a footprint of what this place was like.

So you see the footprint of this big house and there was like a double retaining wall around the whole thing.

It encloses I don't know maybe four or five acres.

I don't think about that much.

So really not that huge.

So when we were there just looking at it and standing back and taking pictures of it,

To me it sort of had the image of a spacious villa.

And this villa was out in this valley.

They lived a lot closer to nature back then than we do.

I mean for one thing the population of the Ganges Valley is somewhere between fifty and a hundred times greater than it was during his day.

So there was just more nature per capita.

And it was an agrarian culture to say we're much more finely attuned to the cycle of the seasons.

And nature was quite generous to them.

The fertile Ganges Valley easily produced more food than they really needed.

So it was quite a prosperous time.

It just was not difficult to feed yourself and your family.

So with all this prosperity there was a lot of leisure time.

So there was time for music and arts and poetry and literature and time for contemplation and time for studying the ancient Vedic scriptures if you were so inclined.

And with that prosperity it was also a time of social innovation.

So somebody could move into some of the small cities and with just a little bit of entrepreneurial energy could rise above the traditional expectations for whatever caste they had been born into.

So this caste system was starting to get a little squishy back then.

The Buddha is sometimes given credit for starting to break that down by inviting people into the sun of all castes.

And I don't want to take away from him for doing that but it actually was going on already.

He was just actually following the trend a little bit in that.

It was also quite possible for hippies to just drop out of the workforce and beg.

There was enough food to go around,

It wasn't a problem.

And a lot of people did.

But it was mostly older men.

So as they got up into their later years they would turn over the family business of the farm to the next generation coming up and they would wander off looking for spiritual fulfillment.

The families back then tended to live in these large multi-generational clusters with all the hubbub that you would imagine with that.

So if you wanted a little bit of peace and quiet you kind of had to wander off into the woods and a lot of people did.

And these wanderers were called bhikkhus,

Which literally means beggar.

A couple thousand years later when the English first came in and saw these people wandering around who they called bhikkhus,

They translated the term as monk because the modern bhikkhus,

And I think the ones back then,

Tended to dress in robes and walk with this contemplative deportment.

But the term actually means beggar.

They had a little bit more reverential attitude towards beggars than we seem to have today.

With all those seekers it was also a time of spiritual innovation.

There were sanghas and people and just all over the place.

And that actually continues on.

When we were traveling in India there was like a guru on every corner,

Most of them riding bicycles.

The tradition says that Sri Gautama grew up in a 5th century BCE version of the Truman show.

Do you remember the Truman show?

Jim Carrey plays this guy who as a baby had been bought by a corporation and then the corporation raised him in a reality TV show with hundreds of actors in this television setting that was bigger than a small town.

And for the first 29 years of his life Truman thought it was all real.

He was the only one that didn't know it was actually a TV show.

So the tradition says that for the first 29 years of his life Sri Gautama grew up in a palace,

A big palace where he was sheltered from all the harsh realities of life until in his 29th year he was finally exposed to disease,

Sickness,

Old age and monks.

And from that he was inspired to go off on a spiritual quest.

That's what the later tradition says.

But in reality his mother died in the first week of his life and so he was raised by his aunt.

And his aunt and his mother were both married to his father,

He had two wives.

So it's hard for me to imagine he grew up all those years with nobody ever mentioning his birth mother.

And also life back then in that time,

For us it was sort of like growing up on a large farm.

You don't grow up on a farm without having a lot of exposure to birth and death of all kinds.

And as I was saying they lived in these large,

Close-knit,

Multi-generational families,

Extended families in which the elders were deeply revered.

So the kids weren't sheltered from the elders.

So it's just hard for me to imagine he would have gone all those years without being exposed to sickness,

Old age and death.

To say that he was sheltered from all that you would have to imagine that he was probably pretty naive,

Unobservant,

Dim-witted and hopelessly idealistic.

But the picture of course that emerges of this guy out of the text is he certainly wasn't naive,

He was very wise,

He was smart,

He could spin on a dime,

Not only debating but also adapting his teachings to the proclivities and inclinations of his students very rapidly.

Very observant,

You read in Iguisutus and there's lots of references and metaphors to all kinds of things in life.

And he certainly was not idealistic,

He had really very little interest in big visions and fantasies and metaphysical speculation.

I may get in trouble for this but in some ways it's more like a farmer in the sense that it's really practical down to earth,

He was interested in the practical down to earth stuff about how you deal with suffering in life,

Not all this speculation.

Is there an indication that he was trained as a warrior since this was a warrior clan?

It was a warrior clan.

I haven't looked deeply enough into that because it seems so disrespectful but there's one story that Yosadāra,

His wife,

Yosadāra's father was not too fond of Śrī Gautama because he just thought he wasn't together enough.

And so there was this big contest where people were showing their skills and bows and arrows and horsemanship and everything else and he beat everybody.

Śrī Gautama.

Yeah,

And so won the respect and etc.

That story has a little bit of a flavor of myth that had been created but you really wonder.

And in terms of exposure to it,

Even if they were sort of gentile warriors,

But there was a lot of fighting going on back then,

But even if they were gentile,

If they were the warrior clan,

Because it was one of the upper castes,

To not have old war stories and battles and fights and all that stuff seems like it would have been part of it.

And also,

Talk about being sheltered,

After he became a spiritual superstar,

His brother-in-law and cousin Devadatta tried to kill him at least three times that we know of.

And it's really hard for me to believe that that sort of family dysfunction suddenly emerged after he became enlightened and wasn't around exposure to that.

Plus the fact we know there's a lot of political intrigue going on and he was in a political family and was right in the thick of all of it.

What is it like to have his cousin try to kill him?

It's usually described as jealousy.

When he wasn't trying to kill him he also wasn't plotting to kill him,

He was trying to split the Sangha and some of the ways he tried to do it he was asking for the rules for the Sangha to be more restrictive,

He wanted it to be more austere and then try to pull people away who were interested in that.

The only difficulty I have in looking at that stuff too literally is that it was all passed down many centuries later through the Sangha,

Through all the people who were cheerleading for the Buddha.

And so it could have very easily been slanted in all kinds of ways.

But I think the fact that he was after him,

There's enough smoke there that there's probably some fire in it.

So the records of his early life are really pretty sketchy but he was born in a higher caste,

He didn't grow up in a monastery and he didn't grow up in a BCE version of a reality TV show.

And I find all this quite encouraging,

Frankly.

I mean I didn't grow up in a sheltered life,

More privileged than some people,

Sure.

And the fact that he was more likely exposed to a lot of the rough and tumble of life,

Including mean cousins and all kinds of stuff,

People trying to kill him,

And still became fully enlightened,

Sort of means that whatever it is he accomplished it wasn't because he was somehow sheltered from all this stuff and it's too late for the rest of us.

It sort of makes it more relevant to the rest of us.

So that's the world that he grew up in.

And to understand his message and how people heard him,

It just helps to have a little bit of that background.

The records of his life become a little bit richer starting in his 29th year.

And I was just tickled too that in the Truman Show it was Jim Carrey who played him,

It was his 30th birthday where the reality of what the TV show was about became known to him and I'm sure there's nothing to that parallel but it sort of tickles me.

In his 29th year his wife,

Yosadara,

Gave birth to Raula.

I don't know if he had other children but it's the only child that we know of of his.

And he talks about looking in on his sleeping infant one evening and what he wanted for Raula was what most parents want for their child.

They want the highest,

Deepest full well-being and richness of life that's possible.

And he realized that he didn't have it to give.

That he didn't actually know how to get that.

And remember he grew up in a wealthy family in a prosperous time and had at his fingertips all the best that culture at that time could produce.

But still things got messed up,

Crops failed,

Cousins were mean,

Roofs leaked,

Relationships drifted,

People died.

As singer-songwriter Paul Simon put it,

Everything puts together sooner or later,

Falls apart.

And so he realized that the lifestyle that he was following there wouldn't give him,

And so he couldn't give it to his son,

The kind of richness and depth that he wanted.

So if he really wanted that for him he had to look elsewhere.

Well another model that was around was all those bhikkhus.

It was pretty rare for somebody his age to go off and become a wandering bhikkhu like that,

But there was a model there and the inspiration and this sense of it was worth looking into.

And as he reflected on this later,

He said he was looking at Raula and he realized that if he didn't go off in that clasp right away that the bond he had with his son would be more than he could possibly overcome and he wouldn't be able to leave.

So he called on his bodyguard,

Chana,

And together in the middle of the night they snuck out of the family compound.

And when they had gotten far enough away,

He took off his clothes,

Put on monk's rove,

Shaved his head,

And traded in the life of a well-to-do warrior for the life of a barefoot monk on a spiritual quest.

So I think of it as the focus of his attention at that point shifting away from the outer world and shifting more into the inner world to see what he could find there.

Some people like to refer to him as a deadbeat dad who walked out on his family responsibilities to pursue his own selfish interests.

You can try to make that case,

But to make it you really have to ignore the whole family context.

His family was embedded in this caring network of people.

He didn't take any of the family resources,

He left it all with them.

And I think of it a little bit more,

It's not unlike an alcoholic father going off to rehab for the sake of his son.

He knew he just didn't have it and so he was going off for his sake.

And after he was enlightened within the first year after that he did go back home and he did reconnect with Raula.

And Raula eventually became one of the youngest monks to join the Sangha and became a fully enlightened arahant.

So he did bring a deeper contentment to his son than he could have as a lay dad.

Did Raula's wife start with none or two?

Yeah,

Padrapani.

Which is kind of an interesting story because it took some convincing to get him to do that because it was misogynistic culture at that time.

And there was… Still is.

And still is.

And still is.

Yeah.

So his focus is turning inwards and particularly in that part of the world for many many centuries the saints and seekers had been developing practices and looking inward and there was a rich variety of tools and practices available to them to try on.

They were all based around a particular view of how the spirit and the world operate together.

The prevailing sentiment was that there are spiritual forces and there are worldly forces and they are in conflict with one another.

And so if you can suppress the worldly forces it makes the spiritual ones stronger.

And by the way as I go through this I would invite you just to reflect lightly as you go along to your own practice in places where this may connect in with it because as you know with this practice as we've learned here the Buddha eventually did not teach that fierce suppression.

And many of you have tried it.

I tried it and found that it just doesn't work.

But there was not another model back then.

And that model really appealed to the warrior mentality,

Suppressing the emotions and the bodies and the instinct and stuff for the sake of a deeper bliss.

So Venerable Gautama's first teacher that we know about that he studied with was a guy by the name of Alara Kalama.

And we actually know about Alara Kalama from outside Buddhist circles.

He was quite well known back then so this is not something that was made up.

He had a very large Sangha and so he went and he trained with Alara Kalama.

And Alara Kalama taught him how to suppress body,

Emotion,

Mental activities and go into a deep state of mental absorption that they called the realm of nothingness.

He redefined those term later but it was called the realm of nothingness.

And he became so adept at this that Alara Kalama invited Venerable Gautama,

We'll call him Venerable now,

He was a monk,

Invited Venerable Gautama to come and lead the Sangha with him.

That they would share it together.

He was so adept at this.

And Gautama declined.

Despite the deep equanimity that can come out of the mental absorption into the realm of nothingness,

It's really just a temporary state.

That inner bliss was not eternal bliss.

So he would come out of that state and there was all this freed hatred,

Delusion and other stuff going on inside him.

I did my own version of this.

When I first started training in this,

I call it SAVE,

Standard American Vipassana,

I was really convinced that I didn't have enough concentration and that that was really getting my way.

So I went in to see Larry Rosenberg who is the main teacher at the Cambridge,

Massachusetts Insight Meditation Center.

Really wonderful teacher,

He's a wonderful man.

I went in to have an interview and I expressed my concern to him about this and he told me,

He said,

You know,

In this tradition you don't need that much concentration.

He said,

You know,

If you can count ten breaths ten times,

That's plenty.

And so me with my German blood went home and dutifully tried to see if I could count one hundred breaths,

Ten breaths ten times,

One hundred breaths without having my attention waver at all.

So breathing in,

One,

Breathing in,

Two,

And if I was going along,

You know,

Breathing in,

Twenty-seven,

Wow,

I'm getting pretty far,

Oops,

I drifted.

Breathing in,

One.

I eventually was able to do it.

It took me nine months.

And I kept on going with it because having done it once,

You know,

So I got to the point where I could reliably count a hundred breaths without having my mind drift.

And then I looked to see what my mind looked like.

And it was like a steel trap.

It was like,

I thought,

Boy,

This is worthless.

There was nothing in that.

So I don't know what happened with Venerable Godamana,

But I used to imagine going into the deeply absorbed states and coming out of it and finding the mind tight and loosen up and there's all this stuff around.

But whatever the case,

It wasn't enough,

It wasn't true freedom,

So he left Alaric Kalama.

His next teacher was a guy by the name of Uddaka Rama Putta.

Putta means son of,

So it was Uddaka,

Son of Rama.

And Uddaka Rama Putta is also very well known in ancient times with all kinds of records even from outside of Buddhism,

Even a larger Sangha,

Very popular teacher,

Large groups.

And his father,

Rama Putta,

Son of Rama,

His father Rama,

Had known and had mastered a deeper state of absorption called neither perception or non-perception.

And Uddaka Rama Putta had not mastered it,

But he knew the instructions and his father was dead and gone.

So Rama Putta was able to give Venerable Gautama the instructions for getting into neither perception or non-perception.

And so Gautama undertook that practice and he was able to master it.

So he passed his teacher and went into a deeper kind of absorption than probably anybody at that time,

Any of his contemporaries could.

And so Uddaka Rama Putta offered to step aside and turn the Sangha over to him,

Venerable Gautama,

And Rama Putta would become one of his students.

Remind me if you want later,

We can go back and I can take some of the stories apart.

So what happened to Venerable Gautama was it was the same thing.

He would go into these deep states and he would come out of it and there were still the seeds of greed,

Hatred and delusion.

So he declined the offer and at that point he seemed to give up on teachers.

And so he went off and practiced on his own.

And as he was doing that gradually there were other monks that were practicing on their own and there was this little group of five or six of them that ended up practicing together in the hills of Rajagaha,

This little town in the Ganges River Valley,

Practicing up there in the mountains.

None of them were the teachers,

They were just companions on the path.

And as he started practicing with them he took on more and more of these aesthetic practices,

You know of deep fasting,

Of wearing very few clothes,

Certainly no contact with women,

Just very,

Very aesthetic practice.

He was down to the point where he was eating very few calories a day and he said that when he touched his stomach he could feel his spine.

His hair began to fall out,

His skin was turning black.

I don't remember if I read in there that he was losing some teeth,

I mean that happens with that deep malnutrition.

And so he was following this stuff and he realized he was right on the edge of death.

You know he had taken those practices as far as they could go.

If he kept on going to that he was going to die.

He still wasn't awakened,

He still was not enlightened.

And so what was he going to do?

He finally accepted that these practices really didn't work.

And there's a way in which,

I still feel like we have a debt of gratitude for him just for that part,

Because he took those practices out as extreme as you can go.

And if he hadn't done that then we could sit here and say,

Well I don't know if he'd gone just a little bit further,

But he was just right on the brink of death.

He couldn't go any further without dying.

So after six and a half years of practice he rejected the path of the spiritual warrior,

The path of this deep aesthetic denial.

Frail and famished he wandered out of those hills,

Wandered out into the Ganges Plain.

And he got,

This is about two or three miles,

And he just ran out of energy.

He just couldn't move any further.

And so he sat down under a tree and just leaned back against it.

Death was very close.

At that time the folk religions in the Ganges Valley were all centered around tree spirits,

Devas.

So every village had a tree in the middle of it that was the home of this tree spirit,

Of a deva.

And so what would happen to the young women when they came of age,

Twelve or thirteen,

Is they would marry the deva.

And the idea was that a few years later they may marry a human,

And who knows whether the human would be faithful,

But the deva would always be faithful to them and always be their protector.

So there was this young woman,

Sujata,

Who had married the tree deva and a couple years later had married a human,

A young man.

And she wanted more than anything else to have a baby,

You know,

By her human husband.

And about the time that Venerable Gautama was wandering out of the hills of Rajagaha,

She realized that she was pregnant.

And she was overjoyed.

It was just her dream what she wanted.

And so she made up this offering to bring to the tree deva.

And one of the traditional offerings was this pudding called kheer that's made of milk and rice and flower petals and spices.

They say it's honey,

Sweet.

They say it tastes similar to human breast milk.

So she made up this gift of kheer and brought it to the tree deva.

And as she approached the tree,

There was this being that was sitting underneath the tree and was black and skin and bones,

Didn't look terribly human,

Had a huge aura.

And so she took it to be the deva.

And so she offered this being,

The kheer.

In fact it was Venerable Gautama.

With all those practices,

The deep absorption,

You can just imagine,

It must have had aura that went out 50 feet and famished and dying,

Etc.

So she gave it to him.

And this is the story of the milk pate?

Yes,

Sujata.

This is Sujata.

Didn't she feed him?

No,

She offered him this.

And this created a huge dilemma for him.

Because as an ascetic,

You know,

That had spent so many years on these practices,

To speak to a woman,

To talk to a woman,

To accept luxurious food,

Sweet foods from one,

To accept kheer from this beautiful young woman,

Was scandalous.

Just absolutely scandalous.

And so there was a lot of his training to just reject it.

But of course he'd become disillusioned with all these practices.

He had rejected them.

And so what was he going to do?

He was on the verge of death.

So he accepted it.

And I think with that act of accepting the kheer from Sujata,

I think that's the moment Buddhism was born.

If you want to pick one symbolic moment when Buddhism appeared in the world,

It was just that simple gesture of accepting that kheer.

Because in doing this he was symbolically embracing the feminine as well as the masculine,

The earth as well as the sky,

The dark as well as the light.

He was opening up to all of it.

And he was moving away from these religions of the extreme towards what he was soon,

Very soon after that,

Articulate as the spirituality of what he called the middle way between all that.

Eventually,

I think she figured out that he wasn't a tree-deva,

But she came back every day to bring some food to him and nourished him.

Then after about a week he had enough strength so that he could get up.

And he walked about half,

Three-quarters of a mile down to the Naranjar River.

The Naranjar River is about 50 or 60 feet wide and very,

Very shallow.

And so he could in a way cross that.

And on the other side of the river was this grove of fig trees.

And it was a quiet,

Comfortable place where he could easily sit and meditate in the shade next to this river.

So he sat down at the root of a tree in the late afternoon and he could sense that all the stuff that he'd been looking for and seeking and struggling and trying to figure out,

It was feeling like it was kind of,

It was like it was beginning to come together.

So when he closed his eyes,

He was no longer tempted to push anything away,

Thoughts,

Feelings,

Everything else.

If you think about it,

His attempts to control the body and mind through all these practices had failed.

So if you can't control it,

What's left to do?

We thought maybe he just ought to observe it,

See if he could figure out how it operates.

And you can't really understand something if you're trying to fight it off the whole time.

So he sat down there with this commitment to just observe what happened,

To see if he could see more clearly how this whole mind,

Body,

Heart,

Spirit,

Energetic system operates.

And so what do you imagine the first thing that happened?

Hindrances.

If you think about it,

It's sort of like if you try to hold a beach ball under water and you relax,

It sort of flies up.

Well for six and a half years he had held the violence that they pushed aside feelings,

Shoved all this stuff down,

Fears,

Irritations,

Desires,

All that stuff,

Had been systematically trying to squelch and suppress all that.

So sitting under that tree when he stopped suppressing them,

They just flew up in his face,

Just a massive amount of stuff,

Just blew up into his awareness.

He had just an incredibly massive hindrance attack.

And of course back then they didn't have the language of modern psychology.

They described inner workings in terms of people and demons and spirits and stuff like that,

Which is kind of how it feels really.

And so he said it was like he was being attacked by ten thousand demons and he was being alerted by ten thousand fair maidens.

So all this stuff was swirling around at him and he was not trying to push any of it away.

He wasn't trying to indulge it.

He wasn't trying to go into it,

Trying not to push it away,

But just to see as clearly as he could what was going on without getting sucked into it,

Without fighting it.

Let his mind and heart expand a little bit so he could see it more clearly,

But it just kept coming,

It just kept coming and swirling and buffeting and draining his energy.

And he began to wonder,

He said,

Well maybe I ought to control this a little bit.

Who am I to think that peace is possible for me?

What am I really doing here anyway?

So a whole lot of doubt came in.

His faith was waning.

And then in the midst of that doubt there was this memory that came back to him when he had been a little boy.

And his father was out in the fields,

He was the head guy,

He was the clan chieftain,

And was leading some kind of agricultural ritual,

Probably a spring planting ritual of some kind.

And he was just a little kid then,

So he was set off at the side with a nurse attendant under a rose apple tree.

And it was a spring morning and they were outside and he just relaxed and let his mind hard expand out and it just became vast and quiet and peaceful and kind and loving and expansive and it was completely effortless.

He didn't have to do anything,

It was right there,

He just relaxed into it.

So sitting under that fig tree with these massive storms of swirls of hindrances and all that stuff flying around,

He remembered the sweetness of that afternoon and it was something he had experienced and he knew that peace was really possible because he had felt it once before,

In fact without ease it was completely impossible.

So that little memory gave him the little extra bit of faith to just not push the inner whirlwind at all,

To just relax into it more and more and as he relaxed into it,

It began to slow down.

Maybe the turmoil was just the residual resistance to it,

It began to slow down until it just became like a quiet breeze.

The metaphor in the text is that all of the spears and arrows that the demons were throwing at him turned into flower petals.

So they didn't actually disappear,

They just ceased to be a problem.

I was meditating in Thailand.

Did I tell you about the dogs?

They don't have dogs and cats as pets in Thailand.

It's a third world country,

It's a poor economy,

It costs a lot to support them,

But they have lots of dogs and cats,

They're just all feral and they're not treated very well.

Except in the wats,

Except they're a monastery so I was in this wat and there they're practicing kindness towards all beings so they feed the dogs and the cats so they love to collect there.

So you get all these packs of dogs in these wats and they do the dog thing,

Trying to figure out who's the top dog and who's the lesser dog and I would be sitting there meditating and these dogs would be trying to kill themselves in the door of my kuti.

In the middle of the night they went on the terrorist watch patrol or something like any little shuffle of anything and they would bark and they would bark,

Bark,

Bark and this ruckus would go through all of them,

They're all over the place.

When I was first there it was incredibly distracting,

These dogs all over the place and this noise.

In fact when I was first shown to my kuti I took my sandals off and a dog picked up one and ran with it.

I had to barefoot run it down.

So it was this incredible mess and then after I was training there for about a week or ten days I was sitting and I realized all the dogs had gone.

And I was delighted,

I couldn't figure out what that was and so I just let my awareness go out there,

No they hadn't gone,

They were all there,

They were howling away as before.

But somehow in me they had just become part of the sounds of life,

They were just part of the movement of energy around me.

It's no longer a problem,

They hadn't changed at all.

And so I think that's what happened to the Buddha,

It was a big time version of that mind was just a little of just feeling all those energies is no longer a problem.

And so he just surrendered into it and it became like a quiet breeze.

And as the mind,

Heart,

Quieted,

Became subtler and subtler there was deeper tension that was down underneath there that would come up the surface and so he would relax into that and spread out into this quiet joy and more would come up and relax until pretty soon there was actually nothing left.

Stuff kept coming up and relaxing until there was nothing left.

So he had gotten into that space of nothingness but without any tension in it,

Was totally at rest.

But he could see that even the attempt to see that he was in nothingness,

Just to actually perceive that,

Would send little tiny ripples out through his awareness.

So he relaxed even perception,

So let go of even perception and went deeper into this place that's called neither perception nor non-perception.

Without perception,

Without memory,

Without consciousness,

There is also no suffering,

Even the nothingness disappeared.

So when the sun came up over the fig trees in the morning,

The turmoil was gone inside and he realized that it was never coming back.

So he had accomplished his goal,

He had become Siddhartha,

He had become a Buddha.

So now what?

So now what does he do?

Well what he discovered was so sublime that he just hung out there in the fig grove for three or four weeks,

Just absorbing all the ramifications of it.

And he realized that what he had discovered was so subtle that he wasn't sure other people could understand it.

And the reality is,

He had done something that is probably as close to impossible as I can imagine.

To be a Buddha,

What that means is to work out your liberation without help from anyone else.

It's nearly impossible to do.

None of us here could become a Buddha.

We could become fully enlightened arahats,

But we've got the support and the guidance from him.

A Buddha is one that works it out without any support.

It took him,

You know,

In the mythology hundreds of thousands of lifetimes.

Very difficult to do.

But he gradually realized that there actually were some people who were very close.

And maybe they could work it out,

Maybe they could get there,

Or maybe not.

But with a little bit of nudge from him or with some inspiration or some instruction,

Maybe they could do it.

So he decided to teach.

And the first person he came upon was this young yogi named Upaka.

And Upaka approached him on the road and as he saw him come he saw there was just something extraordinary about this guy.

There was just,

You know,

This carriage and aura and all that.

And so he said,

Who are you?

And the Buddha says,

I woke up.

And Pali,

The word for wake up is buddha.

So buddha means one who has awakened.

So that eventually became the name of the title that stuck with him.

And then Upaka said,

Well who is your teacher?

Who did you learn this from?

And the Majjhima Gaya number 2625,

The Buddha answers Upaka truthfully and with,

You know,

He's just been out there and he's so inspired that all his words come out in verse.

And so when Upaka asks him,

Who is your teacher?

The Buddha responds,

I am the one who has transcended all,

A knower of all,

Unsullied among all things,

Renouncing all by craving,

Ceasing,

Freed.

I have no teacher.

And no one like me exists anywhere in all the world with all its gods because I have no person for my counterpart.

And he goes on like this for several minutes.

So I invite you to put yourself in Upaka's place.

So you're going through some public thoroughfare,

Maybe through a subway station,

And here's the sky that seems to be light and sleet and glowing.

And so you extend a polite greeting and he replies by rapping in cadence.

I am the accomplished one in the world.

I am the teacher supreme.

I am alone and the fully enlightened one whose fires are quenched and extinguished and on and on.

What would you think?

Would you think he was on drugs?

So the suttas describe Upaka's reaction.

And this was said,

The ascetic Upaka said,

May it be so friend.

Shaking his head,

He took a by-path and departed.

So he took the Buddha to be in that case and just kind of scooted away as soon as he could.

They wanted to get involved with this guy.

So I just love that scene.

I just imagine the Buddha sitting there watching Upaka going down the road and kind of thinking,

I don't know,

That didn't work so well.

Do you know that feeling?

For twenty-five years I would come into the pulpit every September having been away from my congregation usually for a couple of months.

I would get a month of vacation and a month of study leave.

And so I would come into the pulpit in September and I was usually inspired and all this stuff that I wanted to share and I would just pour myself into those early fall Septembers and people would greet me at the door with these blank stares and say,

You know,

Very nice,

Wonderful effort.

And I would think,

That didn't work very well.

And what the problem was,

Was that I was very connected with my inspiration but not with them.

And so I went right past them.

So in the days and weeks after that as I was reconnecting with the congregation,

I would go around and I would always carry in the back of my mind two questions.

One is,

What are they most concerned about?

And the other is,

Do I have anything useful to say about that?

And within a couple of weeks they were greeting me at the door with good eye contact and comments about the content and we were back in the groove again.

So I think most of us have experienced that,

You know,

Where we get so inspired that we just actually speak right past the person.

Being an enlightened Buddha doesn't mean that you know everything about everything.

It just doesn't.

Larry Rosenberg talks about this monk that he met in Korea who was probably as clearly,

You know,

Just exquisitely trained and still believed the world was flat.

So again there's this scene with Apaka disappearing down the path with,

You know,

Muttering under his breath and Buddha thinks,

You know,

That didn't go so well.

I think I need a different approach.

So a number of days later he,

On the outskirts of this little town called Sarnath,

Which is about 13 or 14 kilometers from the center of Varanasi,

This ancient,

Ancient city.

The dogs here are too friendly,

They're not keeping control.

He ran across his old meditation buddies,

These five ascetics in this deer park.

And this time when he met them he listened and sensed what their concerns were and spoke to those concerns and spoke,

You know,

In a language they can understand.

And the world basically hasn't been the same since.

By the end of that first conversation with them one of those five kandanya had become fully enlightened arahats.

And the other four had to practice with what he had said for a few days but just very quickly they became arahats.

I think that we owe a debt of gratitude to.

.

.

Days of life take all different textures.

So just send a little kindness,

Kind of soften into it.

So you can kind of feel the pain that goes through your system a little bit.

So don't hold on to it,

Just let it run right through.

I hired him.

No.

Just let it run.

What's happened?

It's okay.

It's another property.

Yeah.

Shutting the window for… Why are you shutting the windows?

Keeping the noise out.

Would you rather have the noise out or the air?

There's plenty of windows out there.

Just these two.

I'm just asking where people are with it.

It's fine.

We need a close-up.

Okay.

Okay.

He could reach out for a while or something.

Yeah.

Problems in paradise.

Yeah.

So,

As I was saying,

I think we can be grateful to Kṛṇāṇa and those others.

He probably would have gone back to the fig grove and disappeared from history.

So,

If accepting Sujata's gift mark the birth of Buddhism,

It was that talk with the the five aesthetics in the wildlife refuge in Sarnath that actually marked it coming into the world.

The talk is known as the Dhammaka Kapavatana Sutta.

The only language that has more A's than Pali I think is the Hawaiian tongue here.

What that means is setting the wheel of Dharma in motion.

Or I just have fun,

I just call it getting the ball rolling.

In that talk he gave to them,

He laid out the core of a meditation practice.

As I've mentioned and as you all know the Buddha is really famous for his capacity to adapt his teachings to the inclinations and the proclivities of who he's teaching.

But there are some core practices that go through all his teachings.

In that first talk to them he laid all that out.

And so he lays out what all of us have to do in one way or another to wake up.

And wouldn't it have been nice if somebody had taken some notes?

But they didn't take notes on stuff,

They didn't write things down.

However,

The five monks did repeat what they had heard,

What they remembered,

Who repeated to others.

So it was passed on and after several hundred years somebody finally wrote it down.

And you can find a later version of that in the Samyam Nikaya,

It's number 5611.

There's actually an article on my website,

It's called Turning Towards,

Where I go through that sutta line by line.

And I won't do all that tonight,

And I won't do that tomorrow either.

But tomorrow what I would like to do is to go back to that and just extract out those three essential practices and we'll take a look at those.

Because we are,

In this practice that we're doing here,

Is an implementation of those three of Samyam,

But it's good to get that larger framework.

But for now I think that's probably enough for me.

So let me open it up to thoughts,

Comments,

Questions.

I was thinking when he was finishing up with the second teacher,

When he mastered that jhana that the teacher wasn't able to get to,

So he came back from that state and he still saw a gradient illusion,

But how was he able to,

What stopped him from thinking,

Oh this is as good as it can possibly get,

Like there's still a gradient illusion,

But I'm higher than anybody else,

And this is as good as life is going to be.

How did he feel like there was something even more than that if nothing existed?

You know it's a great question,

I have no idea.

If we had a Buddha we could ask him.

But I'll tell you the closest,

I've come to that myself,

It's a pearl,

It's not the same thing at all.

But when I was looking at the refugees at one point,

And my thought was,

What if this isn't true,

What if taking refuge in the Buddha and the Dharma and the Sangha really don't make any difference,

How would I ever know that?

Maybe they work really well right up to the end and then they collapse,

The only person that could answer that would be a totally enlightened person.

I didn't know any totally enlightened people.

And so what am I doing this for?

And then what I realized,

Well maybe none of it works,

But what else am I going to do?

What else are you going to do?

Maybe it will work,

Maybe it won't.

But as Molly Oliver,

Mary Oliver,

It's a poem about the grasshoppers at the end.

So what do you want to do with one wild and wonderful life?

And so I was looking at the refugees and I thought,

Well,

You know,

If freedom is not part of my true nature,

If I have to change something essential about who I am,

Forget that,

That's never going to work.

If I have to go against the laws of nature,

I have to go against the Dharma in order to get free,

Well that's not going to work either because they're a lot bigger than I am.

But what if they do work?

And so what am I going to do with my life?

So I'm going to sit back and drink beer or to keep on practicing with it and see how far you can go.

I would like to think,

But this just may be a desire on my part,

That he had a little more inspiration or clarity or faith or something than I did.

But I think even without that,

It's like if you get over the bummer,

Maybe it doesn't work,

And just look at what your options are.

It's like,

Oh,

I mean,

What the heck?

What else is there anyway?

And as he described it,

His path is good in the beginning,

Good in the middle and good at the end.

So he's sort of well past the middle,

So there's stuff that works up to a certain point.

But it is an interesting one to contemplate.

And I don't know an answer to that other than just saying,

What are your choices?

To me,

It just raises the question of if there's a Buddha that is able to get to enlightenment without having anyone keep on that path,

And he was one of the only ones at the time that went past the last stage before that,

Then how do we know there's not an uber-Buddha or a Buddha square where there's even a stage beyond enlightenment that no one has just gotten to yet because you hit full enlightenment and Buddha taught you that path and it seems like the end of the path.

So I don't know if we want to go down this one,

But I'll just mention it and see if we want to run with it.

You know,

Ken Wilber and stages of consciousness that unfold.

And so what we're talking about with a Buddha are actually affective states.

And so that's one line of development of direct experience.

And there's another line of development,

Which is how you process information and assign meaning to it.

It's your understanding of that.

And those stages of consciousness have been,

And humanity have been,

Steadily evolving in terms of what's possible.

And there are clearly some new stages that are just starting to emerge that we don't know much about.

So Ken Wilber looks at it and he says,

Well,

What enlightenment really is,

Is that the capacity to go with affective states out and far completely into the non-dual,

Etc.

,

Those techniques in some capacity to do that have been around for a long,

Long,

Long time.

But it's these stages of development that keep evolving.

So in the Buddha's time,

There was no pluralistic point of view.

So there was what looks to us like sexist misogyny,

But there wasn't any other choice that was actually in the consciousness of people.

What about the Vedas,

All the tradition in there,

The Vedic traditions,

Wasn't that happening as well?

So people were getting enlightened.

Right,

Yeah,

Yeah.

They were getting something.

Yeah,

They were getting something.

The point was,

Is that what Ken Wilber says is that being enlightened means that you can go through all those states and you're at the highest level of consciousness that's available.

And that's going to be constantly changing,

Constantly evolving.

In other words,

If we could transport the Buddha in the 21st century,

Would he make us fully enlightened?

Certainly in terms of the deep states and stuff he could get into.

And he was way beyond his time because the highest stage that was generally available was mythic literal at that time,

Which is sort of equivalent to modern day fundamentalism.

And that's why,

And what he talked about in terms of we have to discover the self,

That's a modern rational value that didn't emerge in the West or anywhere in any significant numbers until about the 15th or 16th century with the Western Enlightenment.

And so he was clearly there.

So he was an outlier and all that.

And the difficulty figuring out what was really going on back then is that the only information we have on it,

That there may be people,

And Buddha clearly was,

That had evolved beyond that,

But most of that information was passed through mythic literal and people with a different type of consciousness.

One time I used the metaphor,

It's sort of like me going to a Stephen Hawking lecture and come back and tell you what he said.

What I could transmit would be deeply limited by my understanding of theoretical physics.

So a lot of what the Buddha was talking about was presumably passed along by people who could not understand it as fully as he did.

So what is the truth of him talking about remembering all his lives and all that?

Is that just part of the folklore of it or is there evidence that he spoke in this term?

It's a huge battle that's going on amongst Pali scholars.

But what it actually comes down to is not technically what's there but just whatever the scholar himself believes and they sort of look at it through that.

So what one side says,

And there's some interesting text on this too,

Where he says to Ananda at one point,

He was talking about people being reborn,

So and so dinos reborn in a higher loka and this one got enlightened and all this sort of stuff.

And then it was Ananda or maybe it was Sariputta,

But one of his disciples asked him why he was talking about that and he said it wasn't to deceive them,

It was to gladden their minds.

And the implication was that,

And he said this a lot,

That he would talk within the vernacular,

He would use whatever the belief systems were there to inspire people.

And so there's some scholars who will take that to say that maybe he didn't actually believe this stuff but he just said it because it was prevailing.

And other people,

Bhikkhu Bodhi for example takes it all pretty literally that he did believe it.

I've seen hundreds of what to me feel like hundreds of lives but I won't,

My language for it is what I like to say is I don't believe any of it but I know it's true.

And there are practices and I've done some with Bhanthi of looking at past lives.

And from my standpoint I'm not sure what's real,

What could be empirically verified if we could time travel or something like that.

But I know the images and stuff that come out of that if you're inclined that way can be actually very useful.

I could explain all these images I've had as just projections out of my psyche and stuff that's happened and that may be true but in terms of practicality of actually working with that.

So I had to forgive myself for massacring a lot of people.

The image was there were some brigands who had,

I was away and they come through and they killed my wife and three daughters and I kind of went crazy and went out after these people.

And in my mind it was better for me to kill somebody that was innocent than to let somebody get away who may have been guilty.

And so what happened in the meditation I have all these images of swords and blood and you know because these things just usually come in a piece and the whole image came through of what had happened and then doing some work with forgiveness etc.

Etc.

And then all that settled down and other stuff opened up.

So whether that was literally true or just images working out I don't know but it was effective for me.

The Buddha ever mentioned things like transmigration and these things that deep alive experimented with?

This gets really tricky and it gets into the text because there are verses and stuff about people moving through ground and levitating and all that stuff.

Here's part of the difficulty is that first of all all the stuff wasn't written down,

Most of it wasn't written down for hundreds of years.

And so just even with the best of intentions as it gets passed along and it kind of gets elaborated I have one scholar who I study with,

Tony,

Who he says you were at the end of a 2500 year game of telephone.

You don't have a game of telephone?

Yeah,

Pass it along.

And so it's very clear that a lot of the other teachings began to filter in to that and there hasn't been,

Scholars are starting to do it now,

But how to separate out what clearly came from the Buddha and what may have come in from other places.

That's been done,

There's a lot of that work that's been done in the Bible so you can separate out what came from John or Luke or whoever the recorder was,

What came from the early church and then there's the pieces left over that may have come from Jesus.

But you know the Bible is about like this and the polycanon is this massive,

Massive amount of stuff and the problems of sorting that out.

So I didn't get an answer there.

So the question is about transmigration of souls and stuff like that.

So he clearly talked about that a lot and whether or not he actually talked about that or it was stuff that was grafted onto it later.

So for example,

I have one teacher who says that he thinks that in terms of stages of enlightenment,

Because there are four stages,

Each has two sub-stages,

That the only thing that was important was actually sowed upon a stream entry and then full enlightenment in our hardship.

But with the Brahmin class that were very much into rebirth and all that stuff there were these others too that were inserted in there and sometimes they were described in terms of the number of rebirths etc.

It sort of reminds me of what happened with the martial arts when they came from Asia.

Because a lot of them they got white belts and they got black belts.

When they started training Americans,

Well they just went all these little gradations of measuring their progress along the way.

And I don't know how to sort that out.

There is one sutta where the Buddha is talking to Ananda and he asks how many kinds of beings are there.

And so in that,

And it's not in the Majjhima Nikaya,

Not in the Devadana Nikaya,

I forget where it is,

And there he goes,

He talks about the eight kinds of noble persons beyond a human.

And he defines them each as a kind of a person.

That these are different kinds of people.

It was actually about,

Because I read that transmigration and these kind of replicating yourself and… Well actually the Buddha didn't believe in transmigration.

So it came from later… Yeah,

Well it was around a long time before him.

But I think… It doesn't seem like a practical thing,

But I did remember that in one of the sutta's he was in two places at the same time.

By location.

By location,

Yeah.

That's what he's… Oh sorry,

By location.

Okay.

That's true of migration.

Okay,

Okay.

Okay,

That was okay.

Well,

The one thing that I would say if you look back into one of my favorite texts is actually the fourth book of Sutta-nipata,

It's called the Agabata,

That scholars believe,

Maybe some believe is one of the oldest texts,

Probably written down there in his life.

And boy what you find in there is really simple and quite powerful and very,

Very human.

And it's the fourth book of the Sutta-nipata and if you're interested in it there are a couple of Aussies who… there were these three who were deep practitioners and one was a poet and there were scholars and they did a translation of the fourth book which is quite poetic.

Usually what happens if you see the Pali version,

Because things do not translate from one language to another,

They just don't.

And so what scholars will do is they'll take this phrase and they'll take a word and they'll expand it out into about seven or eight words to give the nuance of it and so you'll end up with a sentence with three or four words and then in Pali it'll be translated into thirty.

And they have done a wonderful job of trying to get the poetry and get it real simple and I'll read you some from one of these evenings.

But what's in there is really simple.

And in the Sutta-nipata there's a whole bunch of those suttas that just begin with him saying,

You know,

I wish you guys would just stop fighting.

They say it's over and over,

The wise don't argue.

It's just very,

Very human.

What do you think the aura is?

What is it in your experience of someone's aura?

Oh,

It's just the energy field.

So if you look at my arm and don't focus on it but just sort of gaze that way.

And can you see it feels like just a little bit of thickness in the air?

You know,

Starting back here and there.

Can you see that?

They call that the etheric body.

That's the densest part of the aura.

And particularly as things quiet down it's easy enough to see.

And is it correlated with having a strong aura with being deeper in the spiritual path?

Sort of him sitting with a tree and having a big aura?

Yeah,

Yeah,

But it can go the other way.

Because I think Hitler probably had a huge one too.

Hitler was incredibly charismatic.

So they're larger and less large energy fields but it doesn't necessarily go with enlightenment.

But presumably someone who is fully enlightened like that.

But also part of that enlightening them is the experience of others of a lightness of warmth and not malicious.

And that's why the Buddhist statues have these little coiffures,

Little pyramids and stuff in their head.

It's like they're talking about a crown chakra and seeing that they all live.

Well this is a Chinese one.

And of course in Christianity it came out as a halo around the head.

Okay,

I've been here a long time.

Anything else?

So from reading the sutras,

The bodhisattva on the night of his enlightenment mentally tried to determine using analytical thinking what the causes of suffering were.

Did I get that right?

I don't know.

That he thought about dependent origination.

That he thought about it in rational,

Analytical terms because of suffering emerged because of some birth of some action that I did.

And that birth of action was dependent on,

For bounties,

A habitual tendency and so on and so forth.

That he actually thought through these stages and then he looked inside of himself to see if that was true.

In other words he postulated it as a theory first.

I don't know.

It doesn't ring true to me.

In the very early texts there are not all those links.

There are about eight.

I'll take eight.

I'll take three.

It's science then.

It's phenomenology.

Right,

We as phenomenologists.

It's not,

Right,

Exactly.

And so it doesn't matter if there's two or ten or twenty.

But he thought about it first analytically and then he went to prove it to himself by looking to see if that's how it actually happened.

For me to buy in that I'd have to have some information about how that story was transmitted.

But we could never find that out.

We don't have that.

So what I always come back to is actually what really feels useful.

Because that's only what makes any difference.

And clearly there is an analytical path.

There is an analytical yoga.

There is a way of doing that.

Most people who use a lot of analysis,

It's really more in terms of trying to deny feelings and push things away.

But there is a way of using the mind that can be analytical and free in that way.

So if that's in the Majjhima Nikaya,

Are you dismissing it as being mythology?

I'm dismissing it as I'm saying that we just don't know.

Because the Majjhima Nikaya did not reach the form that we've got it in now until at least 300 years after he died.

And so to sort out what were later insertions.

So here's another thing.

We know that after the Buddha died that there was a time in that area where there was a lot of competition to win people into various Sanghas.

So my guru is better than your guru.

So we have Alara Kalama and Adhaka Ramaputta,

Very,

Very big,

Famous,

Famous people.

And so the Buddhists come along and say,

You know,

My guy,

My guy studied with Alara Kalama and Alara Kalama invited him to study but it wasn't enough for him.

And Ramaputta said that he surpassed him but it wasn't enough for him.

So do you want to come be a Buddhist or do you want to go to Ramaputta?

We have no idea if that happened but we know that that kind of stuff was going on and it would be naive to actually dismiss that as an impossibility.

So are you looking at the Buddhist,

The scope of the Buddhist text as being probability?

The whole thing is like probability.

Well what I'm looking at and what I'm hoping people will do more and more of is actually what's been done with the Bible and actually sorting out.

And you'll never know whether a particular thing came from the Buddha but actually sorting out stuff that clearly could be contaminated from other sources.

And then see what's left there and just look at that.

And the little bit of work that's been done on that I actually find inspiring.

But I think we're stuck with all of this stuff if we sort of get what we can out of it,

Take into our own practice,

See what makes sense and actually work with it.

But I don't think we'll ever know the literal truth of it.

Well the historical stuff we could never know.

But certainly the Dharma,

The teachings,

We can explore the reality of those within our own lives,

Within our own biology.

Exactly.

I mean,

Right,

So,

I mean,

Well I think it's like,

It's the history that you just went through.

Yeah.

It's lore and yes it's so,

And there had to be somebody there because the stiff stuff didn't come out of thin air.

And how much of the history is true,

It really doesn't matter really.

But the teachings that come out in terms of the Dharma is verifiable.

Right,

Right,

Right.

And so there is science,

But the rest of it is history.

Yeah,

It's empirically verifiable.

For me the only reason for going through those stories is actually to sort out what clearly is myth from what might have been there to get some understanding of what those words might mean in their cultural context and what he actually did and what gets laid on top of it.

So who's doing the best work in terms of sifting through the various,

The Pali texts?

Because pre,

Whatever would be,

We could determine would be sort of pre-Tiravada era or proto-Tiravada era,

Proto-Buddhist,

Proto-Buddhist.

Before Buddhaghosa.

Yeah,

At least if not.

Yeah.

Right.

So who's doing the best work in that?

Andy Olinsky,

John Peacock,

Lee Brazington.

Lee Brazington says.

Richard Gombridge.

That he thinks 20% of the suttas are all that might be original.

But he said it in a very cynical way.

I wouldn't,

I'm not sure about that.

I'll check out the other guys.

Well I'm just,

I'm feeling the energy of the room.

I think people are getting tired so I want to see if there's other stuff that's related to practice and we can go on on this stuff.

It's a lot of fun but we're not all Buddhist nerds.

So the question I have,

In reading the suttas is like reading the Bible.

So what creates the evolution,

I mean I think it's coming back to Chris and Eric's question,

What is creating within Buddhism the evolutionary movement within itself?

And is sorting all this scholarship out at all helpful?

Yeah,

Yeah.

I have no idea.

Well the question comes from,

We hear in the Dalai Lama and others that as Buddhism gets transferred from culture to culture it changes.

So it went to Tibet and went through a huge change,

It went into China and Chad and it became Zen,

You know all these formulations.

Are we just getting Buddhism light here?

Light.

I think that what we get are paradigms which are just things to try out and see what happens.

And I think what's happening in the West now is actually a little bit in the other direction that there's actually some filtering out to come.

So for example John Peacock and a lot of other people,

What they're looking at,

The various suttas that come out of those various traditions and find which ones are the same as some indication that they have some historical lineage.

So in some way they're sorting out.

What happened is those three main branches were separated and isolated just geographically and we're in a position now to look at all of them at once.

And so what you actually do with that becomes very,

Very complicated but we've got the possibility of looking at that and seeing what comes out of it.

So I guess the underlying question is,

Isn't it starting to become institutionalized?

It's very institutionalized.

Terravatan,

I mean it's like you've got to go through these systems and structures and you lay outside of the pale to some degree because you are this renegade,

You know,

We've got to do this other thing and people say,

Whoa.

Yeah,

So I'm following my own instincts and inspirations and maybe some of it's alluded and maybe some of it's not but at some point I think we're all just kind of stumbling through this.

But I am interested in looking at questions.

For example,

All this business about it's more advantageous to give money to a monk than to a non-monk because monks leave more suffering,

There's more merit,

Etc.

,

Etc.

But who is transmitting these beliefs?

Are they monks?

Well that's rather convenient.

So what I do is I look at it and if something doesn't ring true to me,

You see if there's alternative explanations.

But the point I'm trying to make is you're doing that for yourself and there's a small group here that says,

Wow,

What you're saying is interesting and you're saying it differently and you're teaching a practice that has a different approach.

But you're anathema to a large group of people within the institutional structure.

And so you're at the edge and we know historically that those at the edge get either crucified or run out of town as the institution gets stronger and stronger.

So what is that saying about where we are with this whole thing of Buddhism coming to the West?

Are you familiar with the work of Claire Graves,

Spiral Dynamics?

Cohen and Beck,

I think.

So what he says,

You're talking about what the evolutionary pressure in this is,

And he says when you have a system that's working well and that people are doing it correctly but it doesn't answer the problems of the day,

That's what actually spurs something else coming out of it.

If a system is broken,

It's not working and people try to fix it.

But when you have a consciousness,

A way of understanding things,

And it doesn't really deal with the issues you are,

That creates the discomfort that actually pushes people to stretch more.

And I think that's not unique to Buddhism or anything else,

But I think that's what the evolutionary force is.

Are you familiar with the Spiral Dynamics in your work?

I'm not very familiar with it.

I've seen some of the Ken Willers talk and stuff,

But I haven't gotten to it much.

Ken Wilber critiques it pretty clearly,

But Claire Graves,

Who was the guy that did the original work on it,

Is really some helpful stuff.

There's a proto-Buddhist movement,

Bhante Willem Ramsey is one of them,

Bhante Punuji,

Bodhicitta.

There's a bunch of people who are in Asia who look at this.

All these Buddhas are cultural.

I know,

I've been to the temples for years.

This is not cultural Buddhism anymore.

This is not cultural Buddhism.

You know,

For me it just comes down to,

Does the technique work?

I don't really care about the other stuff.

And that's what he taught,

Technique.

Because I've had so much more success with this technique.

Well,

And what's beautiful about that,

Because all techniques,

Frankly,

Will run out of gas at some point.

What we're looking at is actually outside of technique.

There can be really powerful ones that actually work for a while.

The Buddha talked about it,

It's a raft metaphor.

The raft gets you across the stream.

You don't want to carry it on the other side,

But you also don't want to get off in the middle of the stream.

So you stay with something while it's working,

And then you get to this uncomfortable place where it runs out of its usefulness.

And then there's a question about what's next and where you go with that.

But certainly when they're working,

They just run with it.

And it's fear that gets you stuck in the system.

Yeah.

I mean,

I've always struggled with these religious structures,

And thankfully I was brought up in Quakerism that actively asked for you to bust out of the walls and search for what works,

What is,

What the isness is under all.

But that feeling as if the only answer is this one I learned,

The Buddhism or the Christianity or whatever structure,

That to explore further or to be is avoided out of fear in my experience.

And I would rather not live in this hot spot of fear.

Okay.

I could go on all night,

But I think… But we already have.

We may have at the point of diminishing usefulness,

Because what it really comes down to in the end is really your own practice.

And that place where all of us feel at times where it gets so clear that you're kind of outside even your own systems,

And then you get sucked back in.

It's those little glimmers that we're really after,

Because that's where it evolves.

And the ones that feel really simple and deeply organic,

I don't know how to describe it.

But you know what I mean,

Right?

Or not.

Whatever.

Amen.

Amen.

Praise whomever.

So… Are you going to build on this tomorrow night?

Is this part one of a two-part exploration?

Well,

I want to take the guts of the Dharmakapatthana Sutta and open that out.

So I'm not going to go on with the story,

But I want to take this,

Because it's his first successful teaching and it's the foundation.

Maybe this makes me an outlier,

But from my perspective,

The essence of it is easily missed.

It's right there in the text.

People miss it.

Yes,

They don't read it.

Three practices.

So this is a preview,

Turning towards,

Relaxing into,

And savoring.

Those are my translations of them,

That's what we'll be talking about tomorrow.

No,

It's the one that they miss.

It's the third one.

It's the nirodha.

When you have moments of peacefulness that come into your practice to… OK.

I thought I could do a short version,

But we will go into it.

Oh,

But it's so cool.

It's so cool,

You know.

And it's right there.

It's just… It's squashing it.

So it was lovely seeing you all individually today.

I really look forward to that.

And I will apologize once and just let that multiply all over the place.

I do my best to stay on time,

But… That's it,

I do my best.

And I'll get to everybody eventually and we'll probably slip off time,

But I want to spend the time that's needed with folks.

And if we have a long conversation we'll take it over to lunch or something like that.

It's really good to see what you guys are doing in your practice.

It's really great.

So just taking a moment to just gently radiate out.

Never mind the words,

There's just that intention for the guy that was yelling out there,

You know.

It's like,

You know,

May you find comfort inside,

You know,

These little peeper beings out there,

You know.