Everything Is In Process

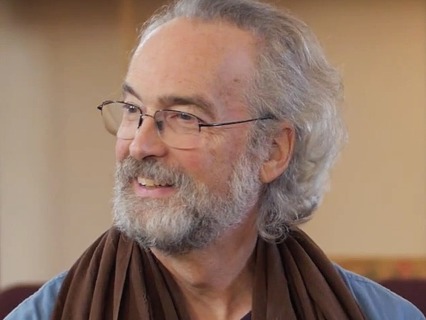

by Doug Kraft

Resting in the Waves-Chapter 2 (In the Buddha’s Words): Introduction to the teachings of the Buddha, how they can be summed up as “everything is in process,” and what that means for us as practitioners.

Transcript

This is Amanda Kimball reading from Resting in the Waves,

Welcoming the Mind's Fluidity by Doug Kraft.

Chapter 2 In the Buddha's Words Suggested Exercise How would you summarize the Buddha's teaching in a word or a simple phrase?

I've posed this question to several Buddha Sanghas.

It's a bit outrageous given the thousands of pages of text attributed to the Buddha,

But the Sangha members are good sports and offered words such as the following,

Mindfulness,

Paying attention,

Awakening,

Staying present,

Enlightenment,

Kindness,

Impermanence.

These familiar Buddhist terms are good suggestions.

My first contribution to the list was not so familiar.

Process.

Or everything is in process.

As I contemplated further,

I settled on an even less familiar phrase,

Welcoming fluidity.

In this chapter,

I'd like to unpack what drew me to this phrase and why I think it's a fair translation of the Buddha's core message,

And we'll look at some of the other terms he used that may not be familiar in everyday English.

But before doing that,

Let's consider the problems inherent in any translation of his teachings into English.

Prakrit,

Pali,

And English.

In the Buddha's time,

Circa 500 BCE,

There were many different languages and dialects in and around the Ganges River Valley.

People didn't get around easily as we do today,

And with the relative isolation varying dialects evolved.

The Buddha probably spoke Magadhi Prakrit,

That is,

The dialect of Prakrit spoken in the ancient city of Magadhi.

But he wandered far during his half century of teaching,

And therefore it's likely that his followers spoke a number of different dialects.

Years after his death,

His monks chose the Pali language to be the uniform repository of his talks,

As they began to write them down for the first time.

Pali and Prakrit are similar,

But not the same.

At that time,

Sacred teachings were not written down.

They were transmitted orally because spoken language was more nuanced and offered more refined expression.

Writing was considered coarse and appropriate only for mundane topics that required little nuance,

Inventory lists,

Business contracts.

His talks were passed by word of mouth from generation to generation.

Like the modern children's game of telephone,

Verbal transmission is vulnerable to having the meaning drift.

It was 600 years before these oral talks were finally committed to writing in Sri Lanka.

Therefore,

It is important to remember that as we read the Buddha's words,

We're reading English translations of Pali translations of the Magadhi Prakrit spoken several millennia ago.

Language was used differently back then.

The Buddha lived long before the scientific revolution.

Language in his day was more evocative than it was definitive.

It was used to evoke meaning rather than to pin it down in a scientific formula.

Also,

Pali has a lexicon of about 50,

000 words,

While English has over a million.

For every word in Pali,

There are an average of 20 words in English.

Pali words thus have to cover a broader range of meanings.

Trying to pin down to a precise definition is not helpful.

Even English words have multiple meanings.

It also helps to know that English has a higher percentage of nouns than most languages,

While Pali has a higher percentage of verbs.

Many Pali terms translated into English nouns are actually gerunds,

Words that end in English with an ing.

Furthermore,

Pali has no articles,

No the,

A,

Or an,

Which make nouns sound even more solid.

The phrase,

Welcoming the mind,

In Pali might be worded more literally,

Welcoming minding.

Pali is more fluid than English.

Because of these translation issues,

The best way to discern finer points of the Buddha's teaching is to hold the meanings of the words loosely and see how they compare with our own experience.

This may not feel satisfying if we want the assurance of precise definitions,

But it's the best we can do.

Process With this in mind,

Let's turn to the idea that process and everything is in process might serve as good candidates for summing up the central theme of the Buddha's teachings.

The word process does not appear very often in Buddhist texts and for a good reason.

The Pali language has no word for it.

It's not in the lexicon.

The Buddha seemed to be saying that everything is in process,

But without a word for it,

He had to use metaphors such as impermanence,

Arising and passing,

Dependent origination,

Changing,

And so on.

If we look inside our own subjective experience,

We won't see solid objects,

Just an ongoing flux and flow of experience.

We cannot trace this flow back to any origin,

And we cannot see any final destination.

We may imagine both a start and an end point,

But we don't experience either,

Just a flux and flow.

Some changes are rapid.

They arise and pass in a few moments.

Some evolve slowly over years,

Yet the mind keeps morphing in subtle and dramatic ways.

It can be unsettling to think we do not have a solid self or a unitary mind essence to hold onto.

So we imagine them,

Yet in the moment-to-moment flow of actual experience,

There is no objective mind or self,

Just subjective shifting experiences.

This shifting obeys the law of cause and effect.

But the essence of the mind and self are ever-changing,

They're processes,

Not things.

Suggested exercise.

What if self is not a thing but a process?

Not a subject nor an object,

But a verb.

What if when the process stops,

There is no thing,

Nothing?

What if self is a byproduct of experience rather than experience being a byproduct of a self?

Anicca Anatta Dukkha Since there was no word for process in the Pali or Prakrit lexicons,

The Buddha's central teaching of the three characteristics of all things is referred to with metaphors.

In Pali,

The three are anicca,

Impermanence,

Anatta,

No unchanging self,

And dukkha,

Suffering.

These three can be reduced to one English word,

Process.

Here's how.

All three Pali words are negations.

This was a common rhetorical device in the Buddha's time.

Rather than state what something is,

We state what it isn't.

This forces us to engage more deeply,

To discern what the positive quality might be,

Particularly if we don't have a word for the positive.

Anicca means impermanent.

The prefix a is a negation in Pali.

Literally the term means not permanent or everything is in the process of changing from one thing to another.

A positive way of saying this is fluidity.

The first characteristic of all things is that they are ever-changing or fluid.

The root of the word anatta is ata,

Which means self or higher self.

The prefix an is a negation.

So anatta translates literally as non-self or no self.

Not only is everything impermanent,

But the self that perceives is also impermanent.

Self is a fluid process.

Another valid translation of anatta is not personal or impersonal.

Put anicca and anatta together and we get the first two characteristics of all things as everything is fluid,

Including the self that perceives,

And everything is impersonal.

It's not about me.

The third characteristic,

Dukkha,

Means suffering.

Dukkha literally refers to a wheel in which the whole of the axle is off-center.

As the wheel turns,

It presses and grinds.

In other words,

From time to time,

Life presses and grinds.

The etymology of the word reveals another meaning.

The root ka means patience.

The prefix du means without.

So dukkha literally means without patience.

When we are impatient,

We suffer.

That's definitely true.

Dukkha underscores the importance of anicca and anatta.

If we don't see the fluid,

Impersonal nature of all things,

Including the self that perceives anything,

Life will press on us.

We're going to hurt.

On the other hand,

If we have patience,

That is,

If we are more welcoming of whatever comes along,

Then we suffer less.

Sati and metta.

The Buddha's primary concern was relieving suffering.

When he said,

Everything is in process,

Anicca and anatta,

He was not making a metaphysical claim.

He was suggesting a way of looking at life as ever-changing.

He advocated cultivating direct insight into how things really are.

Meditation is a process of helping us see simply and accurately how life is.

As mentioned in the introduction,

Two Pali words commonly associated with his meditation are sati and metta.

Sati means mindfulness or bare attention without commentary.

However,

Since Buddhism makes little distinction between mind and heart,

Sati can also be translated as heartfulness.

Meta is usually translated as loving kindness.

However,

The root of metta is metra or friend.

So metta is more accurately translated as friendliness.

Meta is not a highfalutin or formal loving kindness,

But a simple ordinary friendliness.

As a verb,

The idea of friendliness implies welcoming.

Warming fluidity means cultivating clear,

Open-hearted friendliness.

Rather than trying to control life or getting engrossed in its contents,

We watch its flow.

Ownership and Control This attitude is implicit in the Buddha's view of ownership.

His view was common in the East during his time and is still common in many native cultures around the world.

It says that we own only what we create and control.

The West has a much more expansive idea of ownership that includes things we didn't create and don't fully control.

For example,

When Europeans began settling in the Americas in the 1600s,

They offered trinkets for large parcels of land.

They thought they were buying real estate owned by local tribes.

They thought that ownership meant jurisdiction over the land,

How it was used,

And who could live upon it.

To those Native Americans,

The land was owned by the gods,

Or the Great Spirit who created it and the natural forces that work upon it.

The countryside itself was available to be used by all who hunt,

Gather,

Or live there.

Humans could no more control land than they could control the seasons or how life grows and dies.

The gift of trinkets just meant they would all share the land together.

It didn't mean the Europeans could overpower Mother Nature or had the right to drive others off.

The land was owned and controlled by the gods,

Not the tenants.

In his own time,

The Buddha also linked ownership to control.

This point is central to the following colorful vignette in the Majjhima Nikaya 35.

In the sutta,

Sakaka is a renowned and brash debater who picks a public fight with the Buddha.

Referring to various aspects of the body and mind,

Sakaka says,

I assert thus,

Master Gautama,

Material form,

I.

E.

Body,

Is my self,

Feeling tone is my self,

Perception is my self,

Thoughts are my self,

Consciousness is my self.

And so does this great multitude of people listening to us.

Sakaka uses the debater's trick of appealing to the prejudice of the audience.

The Buddha responds,

What has this great multitude to do with you?

Please confine yourself to your own assertion.

The Buddha continues,

I'll ask you a question in return.

Answer it as you choose.

Would a head anointed noble king,

For example,

King Pasannadi of Kosala or King Ajatasattu Vedahiputa of Magadha,

Exercise the power in his own realm to execute those who should be executed,

To find those who should be fined,

And to banish those who should be banished?

Sakaka agrees that kings have such power.

The Buddha continues,

When you say material form is my self,

Do you exercise any such power over that material form as to say,

Let my form be thus,

Let my form not be thus.

For example,

Can Sakaka turn his arm into a wing?

Sakaka remains silent.

The Buddha presses him for an answer,

Saying,

If anyone,

When asked a reasonable question up to three times by the Tathagata,

The Buddha,

Still does not answer.

His head splits into seven pieces there and then.

A spirit holding an iron thunderbolt appears in the air above Sakaka.

Sakaka is terrified.

No Master Gautama,

He concedes,

I can't make my form,

I.

E.

My body,

Be anything I want.

The Buddha seems to rub it in.

Pay attention to how you reply.

What you said afterward does not agree with what you said before.

The Buddha goes on,

When you say feeling tone is my self,

Do you exercise any such power over that feeling as to say,

Let my feelings be thus,

Let my feelings not be thus.

No Master Gautama.

The Buddha continues through perception,

Thoughts,

And consciousness.

The Buddha wins the debate,

But he continues with the Dhamma teaching.

Since all aspects of the body and mind are impermanent and subject to change,

That is,

They're fluid,

Adhering to them leads to suffering.

He said,

When one adheres to suffering,

Resorts to suffering,

Holds to suffering,

And regards what is suffering thus,

This is mine,

This I am,

This is my self,

Could one ever fully understand suffering or abide without suffering?

Sakaka concedes.

In the words of the sutta,

He sits silent,

Dismayed,

With shoulders drooping and head down,

Glum and without response.

The sutta ends on a positive note.

After conceding several more Dhamma points,

Sakaka acknowledges that he has been bold and impudent.

He embraces the Buddha's teaching and offers a meal to the Buddha and his followers as a way of expressing gratitude.

Not metaphysical.

Notice that the Buddha is not making a philosophical or metaphysical claim.

He is just defining ownership as having control.

Since we ultimately don't have control over the body or mind,

We don't own them.

And if we don't own them,

They certainly are not ours.

They are not mine,

Me,

Or myself.

Because logic is compelling even if the conclusion is disconcerting.

Most people tacitly assume they own the body and mind they live with.

Just because we can't control them,

Doesn't mean they are out of control.

They obey natural laws.

If we understand these laws and work with them,

We can influence the body and mind.

We can give it food to abate hunger.

We can give it rest to lessen fatigue.

We can give it medicine to reduce illness.

We can meditate to soothe thoughts.

We can influence the body and mind.

But they are not ours,

And we are not them.

Familiarity.

The idea of ownership can be overstated.

The word mind doesn't always imply control.

When I say my wife or my kids or my tree,

I'm not claiming I control them.

An ordinary citizen of Kasala may refer to Kasala as my town,

With any illusion of being in charge.

Sometimes the word mine just means it's familiar to me,

Or I welcome it.

Perhaps we confuse familiarity with ownership and self-identity.

I am familiar with my family.

The Kasalans were familiar with their town.

All of us are familiar with our bodies and minds.

We travel with them all the time.

I like the phrase,

The mind has a mind of its own.

It's helpful to think of the body and mind as travel companions.

If we relate to them in a welcoming manner and get to know the natural laws that govern how they work,

We can exert some influence.

But in doing this,

We're obeying natural laws rather than trying to control or make the laws.

This helps us navigate life rather than try to control it.

We're the navigator,

Not the pilot.

We have influence,

But not full control.

The senses.

Ownership,

Control,

And familiarity are related to the senses.

Through sense perception,

We know the world around us and the relationship between out there and in here.

And here there's a chart on the page showing the sense organs,

The objects they perceive,

And the sensation through which they do that.

The eye perceives colors and shapes through seeing.

The ear perceives sound through hearing.

Nose perceives scent through smelling.

The tongue perceives flavors through tasting.

The skin and body perceive felt objects through touching.

The mind perceives thoughts through thinking.

And the body perceives emotions through feelings.

Western science describes five senses.

The Buddha describes six.

I find it helpful to consider seven.

The first four senses have discrete organs associated with them.

Eyes,

Ears,

Nose,

And tongue.

The fifth has a generalized organ,

The skin.

It also includes the body in general.

Some touch sensations are not felt by the skin but arise deep inside.

Nausea,

Headaches,

Muscle soreness,

Etc.

For the Buddha,

The sixth sense,

Modality,

Is thinking.

The organ is the mind,

Which does not have a discrete place in the body.

In the West,

Many believe thoughts arise in the head,

But other cultures view thoughts as arising in the chest,

Or nowhere specific.

The Western attribution of thoughts to the head is the culture rather than physiology.

The Buddha was not naive.

He acknowledged that mind-sense is different from the physical senses,

But for the purposes of training,

We can treat it the same way we treat the physical senses.

The organ is the mind,

The object is thought,

And the sensation is thinking.

Suggested Exercise Try observing the thinking process apart from its content.

Does it seem to arise in some body?

If so,

Relax that area.

As mentioned earlier,

The Buddha made little distinction between thoughts and emotions or between mind and heart.

They're conjoined for purposes of spiritual training.

However,

As a psychotherapist,

I find it helpful to treat emotions as a seventh sense.

Emotions can arise throughout the body.

Anger tends to start in the pelvis,

Rise up the back the way an animal gets its hackles up and move out into the arms and fists and up into the teeth which get bared and the eyes which glare.

Fear,

On the other hand,

Tends to drop down the front of the body.

Excitement can spread throughout the body,

Including into the fingers and toes.

Compassion arises in the chest and flows up into the arms and head,

And so on.

What is most important in spiritual training is not adopting a Western view,

A Buddhist view or my view.

The Buddha was not interested in philosophical debate.

What's important is seeing how we relate to these sensory modalities and how they operate in our experience.

Which experiences do we identify with,

Thinking,

This is me,

This is myself,

And which ones do we relate to as being out there and not me?

And finally,

Which experiences are in the middle ground,

Not something I own,

But something I feel I own and should control?

For most people,

The discrete senses are out there,

I see a sunset,

Hear a bird,

Smell a fragrance and taste some ice cream.

Touch sensations,

On the other hand,

Feel more personal.

We're more comfortable touching someone we feel close to than we do a stranger.

Thoughts and emotions may float back and forth between me and not me.

Some people identify closely with their thoughts,

This is just who I am.

Others may not,

I don't know where that thought came from.

Similarly,

Some people identify closely with their feelings,

While others may sometimes see them as foreign intruders.

Nevertheless,

The more clearly we observe the various sensing modalities and our responses to them,

The more we see them dispassionately as phenomena that arise,

Morph,

And fade.

They are merely experiences that come and go,

They are not me,

Mine,

Or who I am.

This is probably why the Buddha treated thought and emotion as a sixth sense that we can experience the same way we know physical sensations.

This gentle dispassion helps us awaken.

Suggested Exercise How do you relate to your body?

Do you see it as you?

This is me,

This is myself.

Or do you see it as something you own?

These are my hands and my feet.

Or is it merely a familiar travel companion?

How do you relate to thoughts?

Are they you or something you own or just a companion?

How do you relate to emotions?

Welcoming Fluidity If we welcome life and its laws,

We can be with them and experience natural contentment and ease.

But we don't own life.

We are part of it,

Rather than it being part of us.

We obey life,

Or we pay the consequences.

Life doesn't obey us.

We are under its control.

Life is not under our control.

Therefore a welcoming attitude toward experience and its natural fluidity is essential to living peacefully with life as it is.

It goes to the heart of the spiritual journey,

Awakening,

And freedom from suffering.

4.8 (8)

Recent Reviews

Cary

June 22, 2023

Great chapter