1:00:42

1:00:42

The Divine Messengers

Rated

4.9

Type

talks

Activity

Meditation

Suitable for

Everyone

Plays

2.4k

The Divine Messengers are an integral part of the Buddhist path. The Buddha encourages us to keep an eye out to see the Divine Messengers every day, as it will be for our benefit for a long time. Never heard of the Divine Messengers? they are all around us, all you need to do is look.

Divine MessengersBuddhismReflectionAniccaDukkhaContemplationDhammaLife ReflectionsContemplation Of RealityMountain AnalogyBuddha Life StoryDeath ReflectionsReflections On IllnessSimile

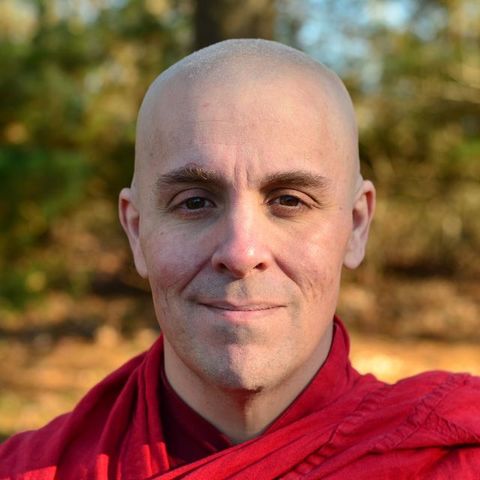

Meet your Teacher

Bhikkhu Jayasara

Bhavana Society - WV USA