49:17

49:17

Talk - Dukkha: Laying Down the Burden

Rated

4.9

Type

talks

Activity

Meditation

Suitable for

Everyone

Plays

6.9k

The First Noble Truth the Buddha gave to us is that of Dukkha, most often translated as suffering, but best translated as "that which is difficult to bear". In this Dhamma talk Bhante J spells out what Dukkha is in various ways, and how we go about abandoning it.

DukkhaSufferingBurdensFour Noble TruthsImpermanenceCravingsAttachmentCharacteristicsFive AggregatesRootsSamsaraNoble Eightfold PathBuddhismNature Of ExistenceThree Roots Of SufferingBuddhist TeachingsCraving And AttachmentTalking

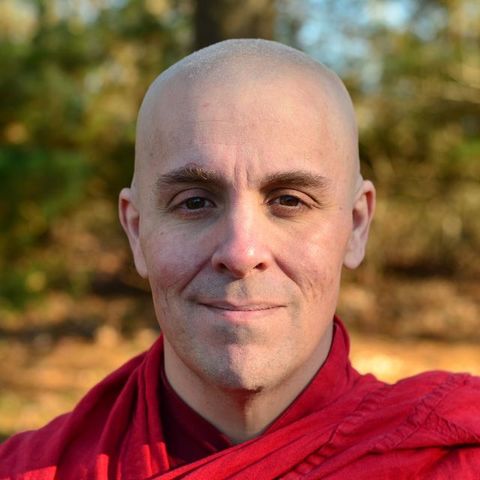

Meet your Teacher

Bhikkhu Jayasara

Bhavana Society - WV USA