1:09:42

1:09:42

The Ten Perfections – Paramitas

Rated

4.9

Type

talks

Activity

Meditation

Suitable for

Everyone

Plays

3.5k

Ajahn describes the Ten Perfections or "paramitas" and how one can hold them and better understand them to benefit one's practice.

PerfectionsParamitasRenunciationMoralityPatienceTruthfulnessLoving KindnessEquanimityWisdomEffortMinimal EffortResolutions

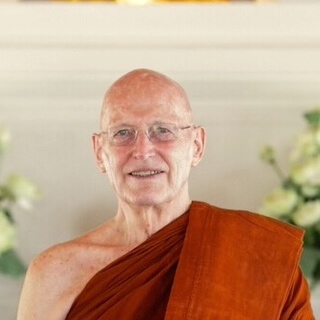

Meet your Teacher

Ajahn Sumedho

Hemel Hempstead, UK