1:13:54

1:13:54

Talk On Opinions

Rated

4.7

Type

talks

Activity

Meditation

Suitable for

Everyone

Plays

3.9k

Ajahn points out how the grasping of opinions of our busy mind prevents the creation of a wise and useful form to develop and appreciate the peace and light that is the natural mind.

OpinionsNon AttachmentImpermanenceInner SilenceInner PeaceMettaRealityPerspectiveDualitySelf ObservationMeditationVipassanaNon DualitySelf AcceptanceMindfulnessEffortSelf CompassionAcceptanceSimplicitySelf RelianceConventional Vs Ultimate TruthSelf Judgment ReleaseMindful AttitudesRight EffortMindfulness In AdversityMeditation SpacesPerspective Change

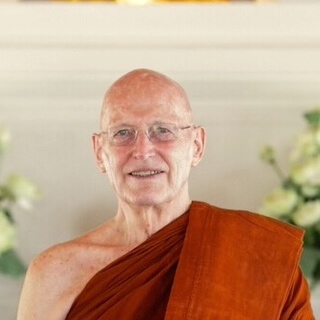

Meet your Teacher

Ajahn Sumedho

Hemel Hempstead, UK