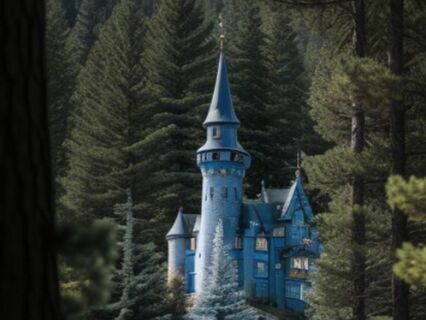

The Blue Castle, Part 7

Please enjoy this continued reading of "The Blue Castle", a delightful 1926 Canadian novel from author Lucy Maud Montgomery, best known for her 1908 book "Anne of Green Gables". Follow along as we hear how Valancy Stirling's dull life as a 29-year-old "old maid" is transformed by a life-changing medical diagnosis and subsequent foray into the world of romance, in search of the man and "Blue Castle" of her dreams!

Transcript

Hello and welcome to part 7 of The Blue Castle,

Which is a 1926 novel by the Canadian author Lucy Maud Montgomery,

Who is best known for her book Anne of Green Gables.

So before we dive into this next part of The Blue Castle,

Let's just take a moment here to let go of the day,

Let go of whatever baggage we're bringing with us into this moment.

Have a nice exhale,

Just being here,

Now,

Nothing more that we have to do right now,

Nowhere else to be.

Let's get ourselves comfortable and relaxed and listen to the next part of the story of The Blue Castle.

Chapter 13 Uncle Benjamin found he had reckoned without his host when he promised so airily to take Valancy to a doctor.

Valancy would not go.

Valancy laughed in his face.

Why on earth should I go to Dr.

Marsh?

There's nothing the matter with my mind,

Though you all think I've suddenly gone crazy.

Well,

I haven't.

I've simply grown tired of living to please other people and have decided to please myself.

It will give you something to talk about besides my stealing the raspberry jam.

So that's that.

Doss,

Said Uncle Benjamin solemnly and helplessly.

You are not like yourself.

Who am I like then,

Asked Valancy.

Uncle Benjamin was rather posed.

Your grandfather,

Wansberra,

He answered desperately.

Thanks,

Valancy looked pleased.

That's a real compliment.

I remember Grandfather Wansberra.

He was one of the few human beings I have known.

Almost the only one.

Now,

It is of no use to scold or entreat or command Uncle Benjamin or exchange anguished glances with Mother and Cousin Stickles.

I am not going to any doctor.

And if you bring any doctor here,

I won't see him.

So,

What are you going to do about it?

What indeed?

It was not seemly,

Or even possible,

To hail Valancy doctorwards by physical force.

And in no other way could it be done,

Seemingly.

Her mother's tears and imploring entreaties availed not.

Don't worry,

Mother,

Said Valancy,

Lightly but quite respectfully.

It isn't likely I'll do anything very terrible,

But I mean to have a little fun.

Fun?

Mrs.

Frederick uttered the word as if Valancy had said she was going to have a little tuberculosis.

Olive,

Sent by her mother to see if she had any influence over Valancy,

Came away with flushed cheeks and angry eyes.

She told her mother that nothing could be done with Valancy,

After she,

Olive,

Had talked to her just like a sister,

Tenderly and wisely.

All Valancy had said,

Narrowing her funny eyes to mere slips,

Was,

I don't show my gums when I laugh.

More as if she were talking to herself than to me.

Indeed,

Mother,

All the time I was talking to her,

She gave me the impression of not really listening.

And that wasn't all.

When I finally decided that what I was saying had no influence over her,

I begged her,

When Cecil came next week,

Not to say anything queer before him at least.

Mother,

What do you think she said?

I'm sure I can't imagine,

Groaned Aunt Wellington,

Prepared for anything.

She said,

I'd rather like to shock Cecil.

His mouth is too red for a man's.

Mother,

I can never feel the same to Valancy again.

Her mind is affected,

Olive,

Said Aunt Wellington solemnly.

You must not hold her responsible for what she says.

When Aunt Wellington told Mrs Frederick what Valancy had said to Olive,

Mrs Frederick wanted Valancy to apologise.

You made me apologise to Olive fifteen years ago for something I didn't do,

Said Valancy.

That old apology will do for now.

Another solemn family conclave was held.

They were all there,

Except Cousin Gladys,

Who had been suffering such tortures of neuritis in her head ever since poor Doss went queer,

That she couldn't undertake any responsibility.

They decided,

That is,

They accepted a fact that was thrust in their faces,

That the wisest thing was to leave Valancy alone for a while.

Give her her head,

As Uncle Benjamin expressed it.

Keep a careful eye on her,

But let her pretty much alone.

The term of watchful waiting had not been invented then,

But that was practically the policy Valancy's distracted relatives decided to follow.

We must be guided by developments,

Said Uncle Benjamin.

It is,

Solemnly,

Easier to scramble eggs than unscramble them.

Of course,

If she becomes violent.

Uncle James consulted Dr Ambrose Marsh.

Dr Ambrose Marsh approved their decision.

He pointed out to irate Uncle James,

Who would have liked to lock Valancy up somewhere out of hand,

That Valancy had not as yet really done or said anything that could be construed as proof of lunacy.

And without proof,

You cannot lock people up in this degenerate age.

Nothing that Uncle James had reported seemed very alarming to Dr Marsh,

Who put up his hand to conceal a smile several times.

But then,

He himself was not a Stirling,

And he knew very little about the old Valancy.

Uncle James stalked out and drove back to Dearwood thinking that Ambrose Marsh wasn't much of a doctor after all,

And that Adelaide Stirling might have done better for herself.

Chapter 14 Life cannot stop because tragedy enters it.

Meals must be made ready,

Though a son dies,

And porches must be repaired,

Even if your only daughter is going out of her mind.

Mrs Frederick,

In her systematic way,

Had long ago appointed the second week in June for the repairing of the front porch,

The roof of which was sagging dangerously.

Roaring Abel had been engaged to do it many moons before,

And Roaring Abel promptly appeared on the morning of the first day of the second week and fell to work.

Of course,

He was drunk.

Roaring Abel was never anything but drunk,

But he was only in the first stage,

Which made him talkative and genial.

The odour of whiskey on his breath nearly drove Mrs Frederick and Cousin Stickles wild at dinner.

Even Valancy,

With all her emancipation,

Did not like it.

But she liked Abel,

And she liked his vivid,

Eloquent talk,

And after she washed the dinner dishes,

She went out and sat on the steps and talked to him.

Mrs Frederick and Cousin Stickles thought it a terrible proceeding,

But what could they do?

Valancy only smiled mockingly at them when they called her in and did not go.

It was so easy to defy once you got started.

The first step was the only one that really counted.

They were both afraid to say anything more to her,

Lest she might make a scene before Roaring Abel,

Who would spread it all over the country with his own characteristic comments and exaggerations.

It was too cold a day,

In spite of the June sunshine,

For Mrs Frederick to sit at the dining room window and listen to what was said.

She had to shut the window,

And Valancy and Roaring Abel had their talk to themselves.

But if Mrs Frederick had known what the outcome of that talk was to be,

She would have prevented it,

If the porch was never repaired.

Valancy sat on the steps,

Defiant of the chill breeze of this cold June,

Which had made Aunt Isabel aware the seasons were changing.

She did not care whether she caught a cold or not.

It was delightful to sit there in that cold,

Beautiful,

Fragrant world and feel free.

She filled her lungs with the clean,

Lovely wind and held out her arms to it and let it tear her hair to pieces while she listened to Roaring Abel,

Who told her his troubles between intervals of hammering gaily in time to his scotch songs.

Valancy liked to hear him.

Every stroke of his hammer fell true to the note.

Old Abel Gay,

In spite of his seventy years,

Was handsome still,

In a stately,

Patriarchal manner.

His tremendous beard,

Falling down over his blue flannel shirt,

Was still a flaming,

Untouched red,

Though his shock of hair was white as snow,

And his eyes were a fiery,

Youthful blue.

His enormous,

Reddish-white eyebrows were more like moustaches than eyebrows.

Perhaps this was why he always kept his upper lip scrupulously shaved.

His cheeks were red,

And his nose ought to have been,

But wasn't.

It was a fine,

Upstanding,

Aquiline nose,

Such as the noblest Roman of them all might have rejoiced in.

Abel was six feet two in his stockings,

Broad-shouldered,

Lean-hipped.

In his youth he had been a famous lover,

Finding all women too charming to bind himself to one.

His years had been a wild,

Colourful panorama of follies and adventures,

Gallantries,

Fortunes and misfortunes.

He had been forty-five before he married a pretty slip of a girl,

Whom his goings-on killed in a few years.

Abel was piously drunk at her funeral,

And insisted on repeating the fifty-fifth chapter of Isaiah.

Abel knew most of the Bible and all the Psalms by heart,

While the minister,

Whom he disliked,

Prayed or tried to pray.

Thereafter,

His house was run by an untidy old cousin,

Who cooked his meals and kept things going after a fashion.

In this unpromising environment,

Little Cecilia Gay had grown up.

Valancy had known Cissie Gay fairly well in the democracy of the public school,

Though Cissie had been three years younger than she.

After they left school,

Their paths diverged,

And she had seen nothing of her.

Old Abel was a Presbyterian,

That is,

He got a Presbyterian preacher to marry him,

Baptise his child and bury his wife,

And he knew more about Presbyterian theology than most ministers,

Which made him a terror to them in arguments.

But Roaring Abel never went to church.

Every Presbyterian minister who had been in Deerwood had tried his hand,

Once,

At reforming Roaring Abel,

But he had not been pestered of late.

Reverend Mr Bentley had been in Deerwood for eight years,

But he had not sought out Roaring Abel since the first three months of his pastorate.

He had called on Roaring Abel then,

And found him in the theological stage of drunkenness,

Which always followed the sentimental maudlin one,

And preceded the roaring blasphemous one.

The eloquently prayerful one,

In which he realised himself temporarily and intensely as a sinner in the hands of an angry god,

Was the final one.

Abel never went beyond it.

He generally fell asleep on his knees and awakened sober,

But he had never been dead drunk in his life.

He told Mr Bentley that he was a sound Presbyterian and sure of his election.

He had no sins that he knew of to repent of.

"'Have you never done anything in your life that you are sorry for?

' asked Mr Bentley.

Roaring Abel scratched his bushy white head and pretended to reflect.

"'Well,

Yes,

' he said finally.

"'There were some women I might have kissed and didn't.

I've always been sorry for that.

' Mr Bentley went out and went home.

Abel had seen that Sissy was properly baptised,

Jovially drunk at the same time,

He made her go to church and Sunday school regularly.

The church people took her up and she was in turn a member of the Mission Band,

A girls' guild and the Young Women's Missionary Society.

She was a faithful,

Unobtrusive,

Sincere little worker.

Everybody liked Sissy Gay and was sorry for her.

She was so modest and sensitive and pretty in that delicate,

Elusive fashion of beauty which fades so quickly if life is not kept in it by love and tenderness.

But then liking and pity did not prevent them from tearing her in pieces like hungry cats when the catastrophe came.

Four years previously,

Sissy Gay had gone up to a Muskoka hotel as a summer waitress and when she had come back in the fall,

She was a changed creature.

She hid herself away and went nowhere.

The reason soon leaked out and scandal raged.

That winter,

Sissy's baby was born.

Nobody ever knew who the father was.

Cecily kept her poor,

Pale lips tightly locked on her sorry secret.

Nobody dared ask roaring Abel any questions about it.

Rumour and surmise laid the guilt at Barney Snaith's door because diligent inquiry among the other maids at the hotel revealed the fact that nobody there had ever seen Sissy Gay with a fellow.

She had kept herself to herself,

They said,

Rather resentfully.

Too good for our dances and now look.

The baby had lived for a year.

After its death,

Sissy faded away.

Two years ago,

Dr Marsh had given her only six months to live.

Her lungs were hopelessly diseased.

But she was still alive.

Nobody went to see her.

Women would not go to roaring Abel's house.

Mr Bentley had gone once when he knew Abel was away,

But the dreadful old creature who was scrubbing the kitchen floor told him Sissy wouldn't see anyone.

The old cousin had died and roaring Abel had had two or three disreputable housekeepers,

The only kind who could be prevailed on to go to a house where a girl was dying of consumption.

But the last one had left and roaring Abel had now no one to wait on Sissy and do for him.

This was the burden of his plaint to Valancy,

And he condemned the hypocrites of Dearwood and its surrounding communities with some rich,

Meaty oaths that happened to reach Cousin Stickle's ears as she passed through the hall and nearly finished the poor lady.

Was Valancy listening to that?

Valancy hardly noticed the profanity.

Her attention was focused on the horrible thought of poor,

Unhappy,

Disgraced little Sissy Gay,

Ill and helpless in that forlorn old house out on the Mestawis Road without a soul to help or comfort her.

And this in a nominally Christian community in the year of Grace 19 and some odd.

Do you mean to say that Sissy is all alone there now with nobody to do anything for her?

Nobody?

Oh,

She can move about a bit and get a bite and sup when she wants it,

But she can't work.

It's hard for a man to work hard all day and go home at night tired and hungry and cook his own meals.

Sometimes I'm sorry I kicked old Rachel Edwards out.

Abel described Rachel picturesquely.

Her face looked as if it had wore out a hundred bodies.

And she moped.

Talk about temper.

Temper's nothing to moping.

She was too slow to catch worms and dirty.

Dirty.

I ain't unreasonable.

I know a man has to eat his peck before he dies.

But she went over the limit.

What do you suppose I saw that lady do?

She'd made some pumpkin jam.

Had it on the table in glass jars with the tops off.

The dog got up on the table and stuck his paw into one of them.

What did she do?

She just took hold of the dog and wrung the syrup off his paw back into the jar.

Then screwed the top on and set it in the pantry.

I sets open the door and says to her,

Go.

The dame went and I fired the jars of pumpkin after her,

Two at a time.

Thought I'd die laughing to see old Rachel run with them pumpkin jars raining after her.

She's told everywhere I'm crazy.

So nobody'll come for love or money.

But Sissy must have someone to look after her,

Insisted Valancy,

Whose mind was centred on this aspect of the case.

She did not care whether roaring Abel had anyone to cook for him or not,

But her heart was wrung for Cecilia Gay.

Oh,

She gets on.

Barney Snaith always drops in when he's passing,

Does anything she wants done,

Brings her oranges and flowers and things.

There's a Christian for you.

Yet that sanctimonious,

Snivelling parcel of St Andrew's people wouldn't be seen on the same side of the road with him.

Their dogs will go to heaven before they do.

And their minister,

Slick as if the cat had licked him.

There are plenty of good people,

Both in St Andrew's and St George's,

Who would be kind to Sissy if you would behave yourself,

Said Valancy severely.

They're afraid to go near your place.

Because I'm such a sad old dog.

But I don't bite.

Never bit anyone in my life.

A few loose words spilt around don't hurt anyone.

And I'm not asking people to come.

Don't want them poking and prying about.

What I want is a housekeeper.

If I shaved every Sunday and went to church,

I'd get all the housekeepers I'd want.

I'd be respectable then.

But what's the use of going to church when it's all settled by predestination?

Don't tell me that,

Miss.

Is it?

Said Valancy.

Yes.

Can't get around it,

No how.

Wish I could.

I don't want either heaven or hell for Steady.

Wish a man could have them mixed in equal proportions.

Isn't that the way it is in this world?

Said Valancy thoughtfully.

But rather as if her thought was concerned with something else than theology.

No,

No,

Boomed Abel,

Striking a tremendous blow on a stubborn nail.

There's too much hell here.

Entirely too much hell.

That's why I get drunk so often.

Sets you free for a little while.

Free from yourself.

Yes,

By God.

Free from predestination.

Ever try it?

No.

I've another way of getting free,

Said Valancy absently.

But about Sissy now.

She must have someone to look after her.

What are you harping on Sis for?

Seems to me you ain't bothered much about her up to now.

You never even come to see her.

And she used to like you so well.

I should have,

Said Valancy.

But never mind.

You couldn't understand.

The point is you must have a housekeeper.

Where am I to get one?

I can pay decent wages if I could get a decent woman.

Do you think I like old hags?

Will I do?

Said Valancy.

Chapter 15.

Let us be calm,

Said Uncle Benjamin.

Let us be perfectly calm.

Calm?

Mrs.

Frederick wrung her hands.

How can I be calm?

How could anybody be calm under such a disgrace as this?

Why in the world did you let her go?

Asked Uncle James.

Let her?

How could I stop her,

James?

It seems she packed the big valise and sent it away,

With roaring Abel when he went home after supper.

While Christine and I were out in the kitchen,

Then Doss herself came down with her little satchel,

Dressed in her green serge suit.

I felt a terrible premonition.

I can't tell you how it was,

But I seemed to know that Doss was going to do something dreadful.

It's a pity you couldn't have had your little premonition a little sooner,

Said Uncle Benjamin dryly.

I said,

Doss,

Where are you going?

And she said,

I am going to look for my blue castle.

Wouldn't you think that would convince Marsh that her mind is affected?

Interjected Uncle James.

And I said,

Valancy,

What do you mean?

And she said,

I am going to keep house for roaring Abel and nurse Sissy.

He will pay me $30 a month.

I wonder I didn't drop dead on the spot.

You shouldn't have let her go.

You shouldn't have let her out of the house,

Said Uncle James.

You should have locked the door,

Anything.

She was between me and the front door.

And you can't realize how determined she was.

She was like a rock.

That's the strangest thing of all about her.

She used to be so good and obedient.

And now she's neither to hold nor bind.

But I said everything I could think of to bring her to her senses.

I asked her if she had no regard for her reputation.

I said to her solemnly,

Doss,

When a woman's reputation is once smudged,

Nothing can ever make it spotless again.

Your character will be gone forever if you go to roaring Abel's to wait on a bad girl like Sis Gay.

And she said,

I don't believe Sissy was a bad girl.

But I don't care if she was.

Those were her very words.

I don't care if she was.

She has lost all sense of decency,

Exploded Uncle Benjamin.

Sissy Gay is dying,

She said.

And it's a shame and disgrace that she is dying in a Christian community with no one to do anything for her.

Whatever she's been or done,

She's a human being.

Well,

You know,

When it comes to that,

I suppose she is,

Said Uncle James,

With the air of one making a splendid concession.

I asked Doss if she had no regard for appearances.

She said,

I've been keeping up appearances all my life.

Now I'm going in for realities.

Appearances can go hang.

Go hang.

An outrageous thing,

Said Uncle Benjamin violently.

An outrageous thing.

Which relieved his feelings,

But didn't help anyone else.

Mrs.

Frederick wept.

Cousin Stickles took up the refrain between her moans of despair.

I told her we both told her that Roaring Abel had certainly killed his wife in one of his drunken rages and would kill her.

She laughed and said,

I'm not afraid of Roaring Abel.

He won't kill me.

And he's too old for me to be afraid of his gallantries.

What did she mean?

What are gallantries?

Mrs.

Frederick saw that she must stop crying if she wanted to regain control of the conversation.

I said to her,

Valancy,

If you have no regard for your own reputation and your family's standing,

Have you none for my feelings?

She said,

None.

Just like that.

None.

Insane people never do have any regard for other people's feelings,

Said Uncle Benjamin.

That's one of the symptoms.

I broke out into tears then.

And she said,

Come now,

Mother,

Be a good sport.

I'm going to do an act of Christian charity.

And as for the damage it will do to my reputation,

Why,

You know,

I haven't any matrimonial chances anyhow.

So what does it matter?

And with that,

She turned and went out.

The last words I said to her,

Said Cousin Stickles pathetically,

Were,

Who will rub my back at nights now?

And she said,

She said,

But no,

I cannot repeat it.

Nonsense,

Said Uncle Benjamin.

Out with it.

This is no time to be squeamish.

She said,

Cousin Stickles voice was little more than a whisper.

She said,

Oh,

Darn.

To think I should have lived to hear my daughter swearing,

Sobbed Mrs.

Frederick.

It,

It was only imitation swearing,

Faltered Cousin Stickles,

Desirous of smoothing things over now that the worst was out.

But she had never told about the banister.

It will be only a step from that to real swearing,

Said Uncle James sternly.

The worst of this,

Mrs.

Frederick hunted for a dry spot on her handkerchief,

Is that everyone will know now that she is deranged.

We can't keep it a secret any longer.

Oh,

I cannot bear it.

You should have been stricter with her when she was young,

Said Uncle Benjamin.

I don't see how I could have been,

Said Mrs.

Frederick.

Truthfully enough,

The worst feature of the case is that Snaith Scoundrel is always hanging around Roaring Ables,

Said Uncle James.

I shall be thankful if nothing worse comes of this mad freak than a few weeks at Roaring Ables.

Sissy Gay can't live much longer.

And she didn't even take her flannel petticoat,

Lamented Cousin Stickles.

I'll see Ambrose Marsh again about this,

Said Uncle Benjamin,

Meaning Valancy,

Not the flannel petticoat.

I'll see Lawyer Ferguson,

Said Uncle James.

Meanwhile,

Added Uncle Benjamin,

Let us be calm.

Chapter 16.

Valancy had walked out to Roaring Ables' house on the Mistarwest Road,

Under a sky of purple and amber,

With a queer exhilaration and expectancy in her heart.

Back there,

Behind her,

Her mother and cousin Stickles were crying.

Over themselves,

Not over her.

But here,

The wind was in her face.

Soft,

Dew-wet,

Cool,

Blowing along the grassy roads.

She loved the wind.

The robins were whistling sleepily in the firs along the way,

And the moist air was fragrant with the tang of balsam.

Big cars went purring past in the violet dusk.

The stream of summer tourists to Muskoka had already begun.

But Valancy did not envy any of their occupants.

Muskoka cottages might be charming,

But beyond,

In the sunset skies,

Among the spires of the firs,

Her blue castle towered.

She brushed the old years and habits and inhibitions away from her like dead leaves.

She would not be littered with them.

Roaring Abel's rambling,

Tumble-down old house was situated about three miles from the village,

On the very edge of Up Back,

As the sparsely settled,

Hilly,

Wooded country around Mystawis was called,

Vernacularly.

It did not,

It must be confessed,

Look much like a blue castle.

It had once been a snug place enough in the days when Abel Gay had been young and prosperous,

And the punning,

Arched sign over the gate,

A-Gay Carpenter,

Had been fine and freshly painted.

Now it was a faded,

Dreary old place,

With a leprous,

Patched roof and shutters hanging askew.

Abel never seemed to do any carpenter jobs about his own house.

It had a listless air,

As if tired of life.

There was a dwindling grove of ragged,

Crone-like old spruces behind it.

The garden,

Which Sissy used to keep neat and pretty,

Had run wild.

On two sides of the house were fields full of nothing but melanes.

Behind the house was a long stretch of useless barrens,

Full of scrub pines and spruces,

With here and there a blossoming bit of wild cherry running back to a belt of timber on the shores of Lake Mystawis,

Two miles away.

A rough,

Rocky,

Boulder-strewn lane ran through it to the woods,

A lane white with pestiferous,

Beautiful daisies.

Roaring Abel met Valancy at the door.

So you've come,

He said,

Incredulously.

I never supposed that ruck of Stirling's would let you.

Valancy showed all her pointed teeth in a grin.

They couldn't stop me.

I didn't think you'd so much spunk,

Said roaring Abel,

Admiringly.

And look at the nice ankles of her,

He added,

As he stepped aside to let her in.

If Cousin Stickles had heard this,

She would have been certain that Valancy's doom,

Earthly and unearthly,

Was sealed.

But Abel's superannuated gallantry did not worry Valancy.

Besides,

This was the first compliment she had ever received in her life.

And she found herself liking it.

She sometimes suspected she had nice ankles,

But nobody had ever mentioned it before.

In the Stirling clan,

Ankles were among the unmentionables.

Roaring Abel took her into the kitchen,

Where Sissy Gay was lying on the sofa,

Breathing quickly,

With little scarlet spots on her hollow cheeks.

Valancy had not seen Cecilia Gay for years.

Then she had been such a pretty creature,

A slight,

Blossom-like girl,

With soft golden hair,

Clear cut,

Almost waxen features,

And large,

Beautiful blue eyes.

She was shocked at the change in her.

Could this be sweet Sissy?

This pitiful little thing that looked like a tired,

Broken flower?

She had wept all the beauty out of her eyes.

They looked too big,

Enormous,

In her wasted face.

The last time Valancy had seen Cecilia Gay,

Those faded,

Piteous eyes had been limpid,

Shadowy blue pools,

Aglow with mirth.

The contrast was so terrible that Valancy's own eyes filled with tears.

She knelt down by Sissy and put her arms about her.

Sissy,

Dear,

I've come to look after you.

I'll stay with you till.

.

.

Till.

.

.

As long as you want me.

Oh,

Sissy put her thin arms about Valancy's neck.

Oh,

Will you?

It's been so.

.

.

Lonely.

I can wait on myself,

But it's been so.

.

.

Lonely.

It would just be like.

.

.

Heaven to have someone here.

Like you.

You were always so sweet to me,

Long ago.

Valancy held Sissy close.

She was suddenly happy.

Here was someone who needed her.

Someone she could help.

She was no longer a superfluity.

Old things had passed away.

Everything had become new.

Most things are predestinated,

But some are just darn sheer luck,

Said roaring Abel,

Complacently smoking his pipe in the corner.

4.9 (35)

Recent Reviews

Becka

July 20, 2025

I forgot this plot twist— at least she is out from under that familial madness… but I love your dramatization of the uncles and aunts 😅 thank you ❤️🙏🏼