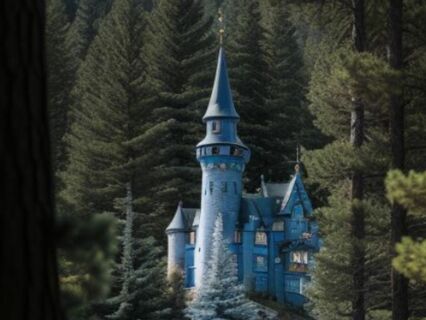

The Blue Castle, Part 15

Please enjoy this continued reading of "The Blue Castle", a delightful 1926 Canadian novel from author Lucy Maud Montgomery, best known for her 1908 book "Anne of Green Gables". Follow along as we hear how Valancy Stirling's dull life as a 29-year-old "old maid" is transformed by a life-changing medical diagnosis and subsequent foray into the world of romance, in search of the man and "Blue Castle" of her dreams!

Transcript

Hello there,

Thank you so much for joining me for this next part of the reading of The Blue Castle which is a novel from 1926 from the Canadian author Lucy Maud Montgomery.

If you haven't yet listened to the preceding parts it doesn't really matter but you can find them in the playlist for The Blue Castle if you would like.

So before we get into this next part let's just take a moment here to really arrive to this moment right now.

Taking a nice deep exhale letting go of the day,

Letting go of whichever baggage we're bringing with us.

There's nothing else for us to be doing right now,

Nowhere else to be,

So we can just relax,

Get ourselves comfortable and enjoy this next part of The Blue Castle.

Chapter 38.

Valancy walked quickly through the back streets and through Lover's Lane.

She did not want to meet anyone she knew.

She didn't want to meet even people she didn't know.

She hated to be seen.

Her mind was so confused,

So torn,

So messy.

She felt that her appearance must be the same.

She drew a sobbing breath of relief as she left the village behind and found herself on the up-back road.

There was little fear of meeting anyone she knew here.

The cars that fed by her with raucous shrieks were filled with strangers.

One of them was packed with young people who whirled past her singing uproariously,

My wife has the fever,

Oh then,

My wife has the fever,

Oh then,

My wife has the fever,

Oh I hope it won't leave her,

For I want to be single again.

Valancy flinched as if one of them had lent from the car and cut her across the face with a whip.

She had made a covenant with death,

And death had cheated her.

Now life stood mocking her.

She had trapped Barney,

Trapped him into marrying her,

And divorce was so hard to get in Ontario,

So expensive,

And Barney was poor.

With life,

Fear had come back into her heart,

Sickening fear,

Fear of what Barney would think,

Would say,

Fear of the future that must be lived without him.

She lived without him,

Fear of her insulted,

Repudiated clan.

She had had one draught from a divine cup,

And now it was dashed from her lips,

With no kind,

Friendly death to rescue her.

She must go on living,

And longing for it.

Everything was spoiled,

Smerged,

Defaced.

Even that year in the Blue Castle,

Even her unashamed love for Barney.

It had been beautiful because death waited.

Now,

It was only sordid,

Because death was gone.

How could anyone bear an unbearable thing?

She must go back and tell him.

Make him believe she had not meant to trick him,

She must make him believe that.

She must say goodbye to her Blue Castle,

And return to the brick house on Elm Street.

Back to everything she had thought left behind forever.

The old bondage,

The old fears.

But that did not matter.

All that mattered now was that Barney must somehow be made to believe she had not consciously tricked him.

When Valancy reached the pines by the lake,

She was brought out of her days of pain,

By a startling sight.

There,

Parked by the side of old,

Battered,

Ragged Lady Jane,

Was another car.

A wonderful car.

A purple car.

Not a dark,

Royal purple,

But a blatant,

Screaming purple.

It shone like a mirror,

And its interior plainly indicated the car cast of ver de ver.

On the driver's seat sat a haughty chauffeur in livery.

And in the tonneau sat a man who opened the door and bounced out nimbly as Valancy came down the path to the landing place.

He stood under the pines waiting for her,

And Valancy took in every detail of him.

A stout,

Short,

Pudgy man with a broad,

Rubicund,

Good-humoured face,

A clean-shaven face,

Though an unparalysed little imp at the back of Valancy's paralysed mind suggested the thought,

Such a face should have a fringe of white whisker around it.

Old-fashioned,

Steel-rimmed spectacles on prominent blue eyes,

A percy mouth,

A little round,

Knobby nose.

Where,

Where,

Where,

Groped Valancy,

Had she seen that face before?

It seemed as familiar to her as her own.

The stranger wore a green hat and a light fawn overcoat over a suit of a loud,

Check pattern.

His tie was a brilliant green of lighter shade.

On the plump hand he outstretched to intercept Valancy,

An enormous diamond winked at her.

Winked at her.

But he had a pleasant,

Fatherly smile,

And in his hearty,

Unmodulated voice,

Was a ring of something that attracted her.

Can you tell me,

Miss,

If that house yonder belongs to a Mr Redfern,

And if so,

How can I get to it?

Redfern!

A vision of bottles seemed to dance before Valancy's eyes,

Long bottles of bitters,

Round bottles of hair tonic,

Square bottles of liniment,

Short,

Copulent little bottles of purple pills,

And all of them bearing that very prosperous,

Beaming moon face and steel-rimmed spectacles on the label.

Dr Redfern!

No,

Said Valancy,

Faintly,

No,

That house belongs to Mr Snaith.

Dr Redfern nodded.

Yes,

I understand,

Bernie's been calling himself Snaith.

Well,

It's his middle name,

Was his poor mother's.

Bernard Snaith Redfern,

That's him.

And now,

Miss,

You can tell me how to get over to that island?

Nobody seems to be home there.

I've done some waving and yelling.

Henry there wouldn't yell.

He's a one-job man.

But old Doc Redfern can yell with the best of them yet.

And ain't above doing it.

Raised nothing but a couple of crows.

Guess Bernie's out for the day.

He was away when I left this morning,

Said Valancy.

I suppose he hasn't come home yet.

But she spoke flatly and tonelessly.

This last shock had temporarily bereft her of whatever little power of reasoning had been left her by Dr Trent's revelation.

In the back of her mind,

The aforesaid little imp was jeeringly repeating a silly old proverb,

It never rains but it pours.

But she was not trying to think what was the use.

Dr Redfern was gazing at her in perplexity.

When you left this morning,

Do you live over there?

He waved his diamond at the blue castle.

Of course,

Said Valancy stupidly.

I'm his wife.

Dr Redfern took out a yellow silk handkerchief,

Removed his hat and mopped his brow.

He was very bold.

And Valancy's imp whispered,

Why be bold?

Why lose your manly beauty?

Try Redfern's hair vigour,

It keeps you young.

Excuse me,

Said Dr Redfern.

Said Dr Redfern.

This is a bit of a shock.

Shocks seemed to be in the air this morning.

The imp said this out loud before Valancy could prevent it.

I didn't know Bernie was married.

I didn't think he would have got married without telling his old dad.

Were Dr Redfern's eyes misty?

Amid her own dull ache of misery and fear and dread,

Valancy felt a pang of pity for him.

Don't blame him,

She said hurriedly.

It wasn't his fault.

It was all my doing.

You didn't ask him to marry you,

I suppose,

Twinkled Dr Redfern.

He might have let me know.

I'd have got acquainted with my daughter-in-law before this if he had.

But I'm glad to meet you now,

My dear.

Very glad.

You look like a sensible young woman.

I used to sort of fear Bernie would pick out some pretty bit of fluff,

Just because she was good looking.

They were all after him,

Of course.

Wanted his money,

Eh?

Didn't like the pills and the bitters,

But liked the dollars,

Eh?

Wanted to dip their pretty little fingers in old Doc's millions,

Eh?

Millions,

Said Valancy faintly.

She wished she could sit down somewhere.

She wished she could have a chance to think.

She wished she and the Blue Castle could sink to the bottom of Mistawis and vanish from human sight forever more.

Millions,

Said Dr Redfern complacently,

And Bernie chucks them for that.

Again,

He shook the diamond contemptuously at the Blue Castle.

Wouldn't you think he'd have more sense?

He'd have more sense.

And all on account of a white bit of a girl.

He must have got over that feeling anyhow,

Since he's married.

You must persuade him to come back to civilisation.

All nonsense,

Wasting his life like this.

Ain't you gonna take me over to your house,

My dear?

I suppose you've some way of getting there?

Of course,

Said Valancy stupidly.

She led the way down to the little cove where the disappearing propeller boat was snuggled.

Does your.

.

.

Your man want to come too?

Who?

Henry?

Not he.

Look at him,

Sitting there,

Disapproving.

Disapproves of the whole expedition.

The trail up from the road nearly gave him a conniption.

Well,

It was a devilish road to put a car on.

Whose old bus is that up there?

Bernie's.

Bernie's.

Good lord,

Does Bernie Redfern ride in a thing like that?

It looks like the great-great-grandmother of all the Fords.

It isn't a Ford.

It's a Grey Slossen,

Said Valancy spiritedly.

For some occult reason,

Dr Redfern's good-humoured ridicule of dear old Lady Jane stung her to life.

A life that was all pain,

But still life.

Better than the horrible half-dead and half-aliveness of the past few minutes.

Or years.

She waved Dr Redfern curtly into the boat and took him over to the Blue Castle.

The key was still in the old pine,

The house still silent and deserted.

Valancy took the doctor through the living room to the western veranda.

She must at least be out where there was air.

It was still sunny,

But in the southwest,

A great thundercloud with white crests and gorges of purple shadow was slowly rising over Miss Starwess.

The doctor dropped with a gasp on a rustic chair and mopped his brow again.

Warm,

Eh?

Lord,

What a view!

Wonder if it would soften Henry if he could see it.

Have you had dinner?

Asked Valancy.

Yes,

My dear.

Had it before we left Port Lawrence.

Didn't know what sort of wild hermit's hollow we were coming to,

You see.

Hadn't any idea.

I was going to find a nice little daughter-in-law here,

All ready to toss me up a meal.

Cats,

Eh?

Puss,

Puss.

See that?

Cats love me.

Bernie was always fond of cats.

It's about the only thing he took from me.

He's his poor mother's boy.

Anyway,

Valancy had been thinking idly that Barney must resemble his mother.

She had remained standing by the steps,

But Dr Redfern waved her to the swing seat.

Sit down,

Dear.

Never stand when you can sit.

I want to get a good look at Barney's wife.

Well,

Well.

I like your face.

No beauty.

You don't mind my saying that.

You've sensed enough to know it,

I reckon.

Sit down.

Valancy sat down.

To be obliged to sit still when mental agony is at its peak.

When mental agony urges us to stride up and down is the refinement of torture.

Every nerve in her being was crying out to be alone,

To be hidden.

But she had to sit and listen to Dr Redfern,

Who didn't mind talking at all.

When do you think Barney will be back?

I don't know.

Not before night,

Probably.

Where did he go?

I don't know that,

Either.

Likely to the woods,

Up back.

So he doesn't tell you his comings and goings,

Either.

Barney was always a secretive young devil.

Never understood him,

Just like his poor mother.

But I thought a lot of him.

It hurt me when he disappeared as he did.

Eleven years ago.

I haven't seen my boy for eleven years.

Years.

Eleven years?

Valancy was surprised.

It's only six since he came here.

Oh,

He was in the Klondike before that.

And all over the world.

He used to drop me a line now and then.

Never give any clue to where he was,

But just a line to say he was all right.

I suppose he's told you all about it.

No,

I know nothing of his past life,

Said Valancy with sudden eagerness.

She wanted to know.

She must know now.

It hadn't mattered before.

Now she must know all.

And she could never hear it from Barney.

She might never even see him again.

If she did,

It would not be to talk of his past.

What happened?

Why did he leave his home?

Tell me.

Tell me.

Well,

It ain't much of a story.

Just a young fool gone mad because of a quarrel with his girl.

Only,

Bernie was a stubborn fool.

Always stubborn.

You never could make that boy do anything he didn't want to do from the day he was born.

Yet,

He was always a quiet,

Gentle little chap,

Too.

Good as gold.

His poor mother died when he was only two years old.

I'd just begun to make money with my hair vigor.

I'd dreamed the formula for it.

Dreamed the formula for it,

You see.

Some dream that.

The cash rolled in.

Bernie had everything he wanted.

I sent him to the best schools.

Private schools.

I meant to make a gentleman of him.

Never had any chance myself.

Meant he should have every chance.

He went through McGill.

Got honours and all that.

I wanted him to go in for law.

He,

Hankered after journalism and stuff like that,

Wanted me to buy a paper for him.

Or back him in publishing what he called a real,

Worthwhile,

Honest-to-goodness Canadian magazine.

I suppose I'd have done it.

I always did what he wanted me to do.

Wasn't he all I had to live for?

I wanted him to be happy.

And he never was happy.

Can you believe it?

Not that he said so,

But I'd always have a feeling that he wasn't happy.

Everything he wanted.

All the money he could spend.

His own bank account.

Travel.

Seeing the world.

Seeing the world.

But he wasn't happy.

Not till he fell in love with Ethel Traverse.

Then he was happy.

For a little while.

The cloud had reached the sun,

And a great,

Chill,

Purple shadow came swiftly over Miss Starwess.

It touched the blue castle,

Rolled over it.

The lancy shivered.

Shivered?

Yes,

She said with painful eagerness,

Though every word was cutting her to the heart.

What was she like?

Prettiest girl in Montreal,

Said Dr.

Redfern.

Oh,

She was a looker all right,

Eh?

Gold hair,

Shiny as silk.

Great,

Big,

Soft,

Black eyes.

Skin like milk and roses.

Don't wonder Bernie fell for her.

And brains,

As well.

She wasn't a bit of fluff.

B.

A.

From McGill.

A thoroughbred,

Too.

One of the best families.

But a bit lean in the purse.

Bernie was mad about her.

Happiest young fool you ever saw.

Then,

The bust up.

What happened?

The lancy had taken off her hat and was absently thrusting a pin in and out of it.

Good luck was purring beside her.

Banjo was regarding Dr.

Redfern with suspicion.

Nip and tuck were lazily cawing in the pines.

Miss Starwess was beckoning.

Everything was the same.

Nothing was the same.

It was a hundred years since yesterday.

Yesterday,

At this time,

She and Bernie had been eating a belated dinner here with laughter.

Laughter.

The lancy felt that she had done with laughter forever.

And with tears,

For that matter,

She had no further use for either of them.

Blessed if I know,

My dear.

Some fool quarrel.

I suppose.

Bernie just lit out.

Disappeared.

He wrote me from the Yukon.

Said his engagement was broken and he wasn't coming back.

And not to try to hunt him up because he was never coming back.

I didn't.

What was the use?

I knew Bernie.

I went on piling up money because there wasn't anything else to do,

But I was mighty lonely.

All I lived for was them little notes now and then from Bernie.

Klondike,

England,

South Africa,

China,

China,

Everywhere.

I thought maybe he'd come back someday to his lonesome old dad.

Then,

Six years ago,

Even the letters stopped.

I didn't hear a word of or from him till last Christmas.

Did he write?

No,

But he drew a check for $15,

000 on his bank account.

The bank manager is a friend of mine,

One of my biggest shareholders.

He'd always promised me he'd let me know if Bernie drew any checks.

Bernie had $50,

000 there and he'd never touched a cent of it.

Till last Christmas,

The check was made out to Ainsley's,

Toronto.

Ainsley's?

For Lancey heard herself saying Ainsley's.

She had a box on her dressing table with the Ainsley trademark.

Yes,

The big jewellery house there.

After I'd thought it over a while,

I got brisk.

I wanted to locate Bernie.

Had a special reason for it.

It was time he gave up his full hoboing and come to his senses.

Drawing that $15,

000 told me there was something in the wind.

The manager communicated with the Ainsley's.

His wife wasn't Ainsley and found out that Bernard Redfern had bought a pearl necklace there.

His address was given as Box 444,

Port Lawrence,

Muskoka,

Ontario.

Ontario.

First,

I thought I'd write.

Then I thought I'd wait till the open season for cars and come down myself.

Ain't no hand at writing.

I've motored from Montreal.

Got to Port Lawrence yesterday.

Inquired at the post office.

Told me they knew nothing of any Bernard Snaith Redfern.

But there was a Barney Snaith.

Had a P.

O.

Box there.

Lived on an island out here,

They said.

So,

Here I am.

And where's Barney?

Valancy was fingering her necklace.

She was wearing $15,

000 around her neck and she had worried lest Barney had paid $15 for it and couldn't afford it.

Suddenly,

She laughed in Dr.

Redfern's face.

Excuse me,

It's so amusing,

Said poor Valancy.

Isn't it,

Said Dr.

Redfern,

Seeing a joke,

But not exactly hers.

A joke,

But not exactly hers.

Now,

You seem like a sensible young woman.

And I dare say you've lots of influence over Barney.

Can't you get him to come back to civilization and live like other people?

I've a house up there.

Big as a castle.

Furnished like a palace.

I want company in it.

Barney's wife.

Barney's children.

Did Ethel Traverse ever marry,

Queried Valancy irrelevantly.

Bless you.

Yes,

Two years after Barney levanted,

But she's a widow now.

Pretty as ever.

To be frank,

That was my special reason for wanting to find Barney.

I thought they'd make it up,

Maybe.

But,

Of course,

That's all off now.

Doesn't matter.

Barney's choice of a wife is good enough for me.

It's my boy I want.

Think he'll soon be back?

I don't know.

But I don't think he'll come before night.

Quite late,

Perhaps.

And perhaps not till tomorrow.

But I can put you up comfortably.

He'll certainly be back tomorrow.

Dr.

Redfern shook his head.

Too damp.

I'll take no chances with rheumatism.

Why suffer that ceaseless anguish?

Why not try Redfern's liniment,

Quoted the imp in the back of Valancy's mind.

I must get back to Port Lawrence before rain starts.

Henry goes quite mad when he gets mud on the car.

But I'll come back tomorrow.

Meanwhile,

You talk Barney into reason.

He shook her hand and patted her kindly on the shoulder.

He looked as if he would have kissed her with a little encouragement.

But Valancy did not give it.

Not that she would have minded.

He was rather dreadful and loud and dreadful.

But there was something about him she liked.

She thought,

Dully,

That she might have liked being his daughter-in-law if he had not been a millionaire a squaw of times over.

And Barney was his son and heir.

She took him over in the motorbike.

She took him over in the motorboat and watched the lordly purple car roll away through the woods with Henry at the wheel,

Looking things not lawful to be uttered.

Then she went back to the Blue Castle.

What she had to do must be done quickly.

Barney might return at any moment and it was certainly going to rain.

She was thankful she no longer felt very bad.

When you are bludgeoned on the head repeatedly,

You naturally and mercifully become more or less insensible and stupid.

She stood briefly,

Like a faded flower bitten by frost,

By the hearth,

Looking down on the white ashes of the last fire that had blazed in the Blue Castle.

At any rate,

She thought,

Wearily,

Barney isn't poor.

He will be able to afford a divorce,

Quite nicely.

Chapter 39 She must write a note.

The imp in the back of her mind laughed in every story she had ever read when a runaway wife decamped from home.

She left a note,

Generally on the pincushion.

It was not a very original idea,

But one had to leave something intelligible.

What was there to do but write a note?

She looked vaguely about her for something to write with.

Ink?

There was none.

Valancy had never written anything since she had come to the Blue Castle,

Save Memoranda of Household Necessaries for Barney.

A pencil sufficed for them,

But now the pencil was not to be found.

Valancy absently crossed to the door of Bluebeard's chamber and tried it.

She vaguely expected to find it locked,

But it opened unresistingly.

She had never tried it before and did not know whether Barney habitually kept it locked or not.

If he did,

He must have been badly upset to leave it unlocked.

She did not realise that she was doing something he had told her not to do.

She was only looking for something to write with.

All her faculties were concentrated on deciding just what she would say and how she would say it.

There was not the slightest curiosity in her as she went in to the lean-to.

There were no beautiful women hanging by their hair on the walls.

It seemed a very harmless apartment,

With a commonplace little sheet iron stove in the middle of it,

Its pipes sticking out through the roof.

At one end was a table or counter,

Crowded with odd-looking utensils,

Used no doubt by Barney in his smelly operations.

Chemical experiments,

Probably,

She reflected dully.

At the other end was a big writing desk and swivel chair.

The side walls were lined with books.

Balancy went blindly to the desk.

There she stood motionless for a few minutes,

Looking down at something that lay on it.

A bundle of galley-proofs.

The page on top bore the title,

Wild Honey,

And under the title were the words,

By John Foster.

The opening sentence,

Pines are the trees of myth and legend.

They strike their roots deep into the traditions of an older world,

But wind and star love their lofty tops.

What music,

When old Eyeless draws his bow across the branches of the pines.

She had heard Barney say that one day,

When they walked under them.

So Barney was John Foster.

But Balancy was not excited.

She had absorbed all the shocks and sensations that she could compass for one day.

This affected her neither one way nor the other.

She only thought,

So,

This explains it.

It was a small matter that had somehow stuck in her mind more persistently than its importance seemed to justify.

Soon after Barney had brought her John Foster's latest book,

She had been in a Port Lawrence bookshop and heard a customer ask the proprietor for John Foster's new book.

The proprietor had said curtly,

Not out yet,

Won't be out till next week.

Balancy had opened her lips to say,

Oh yes,

It is out,

But closed them again.

After all,

It was none of her business.

She supposed the proprietor wanted to cover up his negligence in not getting the book in promptly.

Now,

She knew,

The book Barney had given her had been one of the author's complimentary copies sent in advance.

Well,

Balancy pushed the proofs indifferently aside and sat down in the swivel chair.

She took up Barney's pen,

And a vile one it was,

Pulled a sheet of paper to her and began to write.

She could not think of anything to say except bold facts.

Dear Barney,

I went to Dr.

Trent this morning and found out he had sent me the wrong letter by mistake.

There never was anything serious the matter with my heart,

And I am quite well now.

I did not mean to trick you.

Please believe that.

Please believe that.

I could not bear it if you did not believe that.

I am very sorry for the mistake,

But surely you can get a divorce if I leave you.

Is desertion a ground for divorce in Canada?

Of course,

If there is anything I can do to help or hasten it,

I will do it gladly,

If your lawyer will let me know.

I thank you for all your kindness to me.

I shall never forget it.

Think as kindly of me as you can,

Because I did not mean to trap you.

Goodbye.

Yours,

Gratefully,

Valancy.

It was very cold and stiff,

She knew.

But to try to say anything else would be dangerous,

Like tearing away a dam.

She didn't know what torrent of wild incoherences and passionate anguish might pour out.

In a postscript,

She added,

Your father was here today.

He is coming back tomorrow.

He told me everything.

I think you should go back to him.

He is very lonely for you.

She put the letter in an envelope.

She put the letter in an envelope,

Wrote Barney across it,

And left it on the desk.

On it,

She laid the string of pearls.

If they had been the beads she believed them,

She would have kept them in memory of that wonderful year.

But she could not keep the $15,

000 gift of a man who had married her out of pity in whom she was now leaving.

It hurt her to give up her pretty bauble.

That was an odd thing,

She reflected.

The fact that she was leaving Barney did not hurt her.

Yet,

It lay at her heart like a cold,

Insensible thing if it came to life.

Valancy shuddered and went out.

She put on her hat and mechanically fed good luck and banjo.

She locked the door and carefully hid the key in the old pine.

Then she crossed to the mainland in the disappearing propeller.

She stood for a moment on the bank,

Looking at her blue castle.

The rain had not yet come,

But the sky was dark and Miss Darwis grey and sullen.

And Miss Darwis grey and sullen.

The little house under the pines looked very pathetic.

A casket rifled of its jewels.

A lamp with its flame blown out.

I shall never again hear the wind crying over Miss Darwis at night,

Thought Valancy.

This hurt her,

Too.

She could have laughed to think that such a trifle could hurt her at such a time.